Peter Sellars: Was Kaija’s music always, even from the beginning, conceived imagistically?

Esa-Pekka Salonen: I think always. I think that was the identity of hers as a composer from the very beginning.

PS: I mean, while the boys were dealing with a lot of theoretical questions and scientific relations…I have a sense that Kaija is always functioning on her inner image?

EPS: Yes. In Kaija’s work, the visual and the aural are linked.

PS: Synaesthetically linked?

EPS: Yes, but not in terms of conventional synaesthesia, where one color would correspond to a harmony or a pitch. It is more like if you were to translate a musical experience into another medium, in Kaija’s case it would be a visual image, although for many others it would be verbal.

PS: Right.

EPS: So we guys were dealing with concepts, and by definition “concept” is something that you define in words.

PS: Right.

EPS: Even in the early days, Kaija was not interested in concepts; and now that you mention it, that was a profound difference. Then there comes a moment in life when you stop trying to translate between language and music and realise that music is in some ways like a butterfly: if you touch its wing, you will destroy something and then it cannot fly any more. Music has to be allowed to be its own thing rather than trying to organise it through another medium. But in Kaija’s work these two kinds of expression breathe the same air, so to speak.

PS: I just do not know this first piece that you’re describing. Is it an immersive, physical experience?

EPS: Well, it’s a process. Kaija’s early pieces were almost always manifestations of one process, so there was one formal idea, and that was the piece, to put it simple.

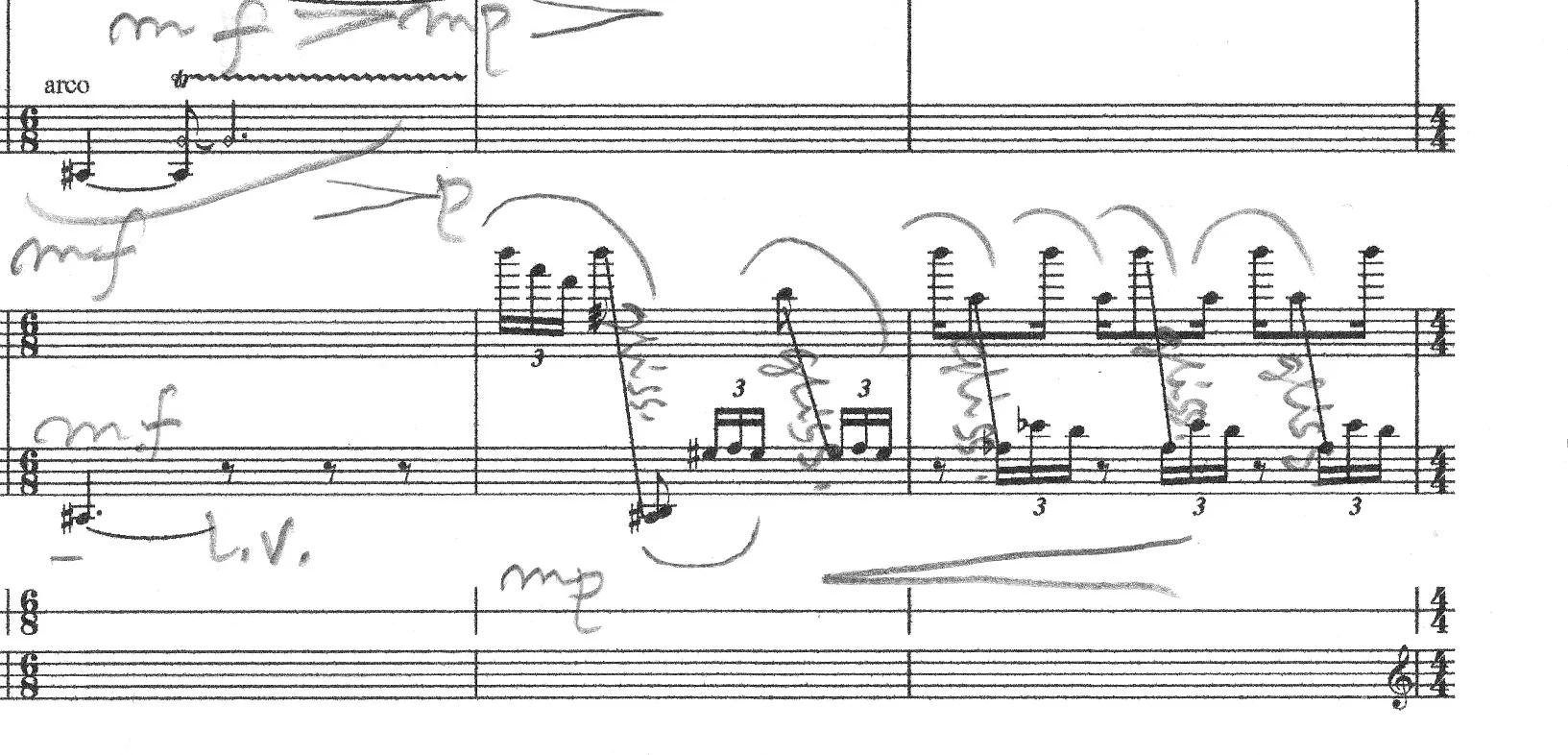

In Verblendungen, the dramatic arc of the piece is formed by a sort of textural metamorphosis. That sounds very theoretical, but it was very expressive. She had made a tape part at IRCAM, and this was at a time when the computer stuff that came out of IRCAM was not very expressive but kind of cold and theoretical, but hers was different. Her metaphor was a painter’s brush, and the piece is one stroke of a brush, basically: the paint is thickest at the beginning of the stroke, and then it thins out and disperses into strands, and every strand is a different shape, and then they all run into nothingness at the end. That was the form, basically. The tape was loosely synchronised with the orchestra, so it was not a click-track job for me.

I remember a very funny thing about that concert. I was a guinea pig for the applied arts school at that time, and one of the classes had an assignment to create a conductor’s outfit. So I was wearing this conductor’s outfit in this concert, and it had a sort of tunic-style upper part that somehow just would not stay on. It was slipping down over my shoulder all the time, so I was conducting this piece, one of my first real concerts, and the world premiere of a really talented friend of mine, and I was fighting with my damn jacket at the same time. But it was fine.

PS: At that time, were you guys still involved in intense conversations and discussions about what everyone was making? Or by that time had she gone away to Paris and was no longer a part of ongoing conversation here?

EPS: Well, what happened was of course that everybody in the core group of the society went somewhere. Kaija went first to Freiburg. She was there for a year or something like that.

PS: Oh, with Ferneyhough?

EPS: Yes, and Klaus Huber, those two. And actually Magnus Lindberg and I, we made it to her diploma concert in Freiburg.

PS: No. No!

EPS: Yes. We took the train through half of Europe and made it to the diploma concert. At that point we had not slept for two days. Kaija was very touched by us being there, and so were her parents. It was kind of funny, because there we were, Magnus and I, we had made it, such a relief; and we were sitting in the first row, and the concert began, and we promptly fell asleep! Because we were so relieved. And Kaija was like: you guys are just hopeless.

PS: It is something special to have friends.

EPS: But we made it there! And that was the big deal.

PS: That’s fantastic.

To read the entire conversation between Peter Sellars and Esa-Pekka Salonen (concluded by a brilliant monologue on Saariaho's work by Sellars), purchase your copy of Music & Literature no. 5 . . .