The following essay appears in Music & Literature no. 5, which contains some 80 pages celebrating the prolific career of Can Xue.

In 1988, the final year of China’s post-Mao, pre-Tiananmen “Culture Fever,” the Shanghai Literature and Art Publishing House organized a conference in honor of two women writers. One was the realist Wang Anyi; the other was the unclassifiable Can Xue, whose first full-length novel had just been published to the same controversial reception as her earlier short work. Her oblique, nightmarish fictions had quickly gained notoriety, and once it became known that a woman was writing behind the pseudonym, criticism had turned personal. The author was said to be too individualistic, or simply too deranged, for significant achievement; her work was called neurotic and scopophilic, “the delirium of a paranoid woman.”¹ Against such charges any author might have taken a conference as an opportunity for self-defense, but it is a mark of Can Xue’s slyness that she chose to do so in the form of a fiction. Addressing her audience, she announced the happy news that in preparation for her lecture, a “male colleague” had given her guidance and even chosen her topic: she would be speaking on “Masculinity and the Golden Age of Literary Criticism.”²

Can Xue at a Conference for Chinese and Japanese Women Writers, Beijing, 2001.

The colleague, in her telling, is affronted not to be giving the lecture himself: “Those people in Shanghai are really blind. How could they invite you there? What does a woman have to say? Such questions should be answered by men. And not any kind of men, but those who have deep philosophical knowledge about things and who have also maintained their masculinity.” In his pique, he kicks apart Can Xue’s tea table—a gesture she finds “well done”—and storms out. She is left to explain his masculine philosophy, which turns out to originate from his childhood in a bandit village where “eight hundred strong men and bewitching women with bound feet” are ruled by a sexually formidable grandfather. By this point in the lecture, the audience would have recognized that they were hearing a parody of Mo Yan’s recent novel Red Sorghum, and by extension an attack on the dominant literary school of the day. All participants in the Culture Fever debates agreed that Chinese literature required a positive program, and one leading view was that it should emulate the rural mythmaking of Gabriel García Márquez, “seeking its roots” in order to “march toward the world.”³ In such an era of slogans, Can Xue’s work could not but cause distress; whatever else it was doing, it was not marching toward anything at all.

The most immediate effect of this lecture was probably to offend the establishment. But for those of us now reading her first novel in translation, twenty-five years later, it makes a good key; for Five Spice Street is among other things an author’s reflection on her newfound public position. The book was originally published as Breakthrough Performance (突围表演), a purposely self-conscious title for a debut novel. At the same time, 突围 suggests breaking free, an escape from entrapment or other immediate danger, and this raises the possibility that the escape itself constitutes the performance, that a kind of Houdini act is being staged. The plot follows a community’s reaction to an outsider, an enigmatic woman whose so-called “performances”—scholarly, sexual, perhaps supernatural—are sometimes threatening, sometimes laughable, and never well understood. Whether they constitute any kind of escape, and whether they have anything in common with Can Xue’s writing itself (which she often calls 表演, “performance”), are questions that the novel keeps in the foreground while deferring anything that looks like an answer. While it might be a fiction about writing fiction, its integrity depends on offering no positive program, nothing that could collapse into the kind of sloganeering that Can Xue mocks in her lecture. This imperative motivates its hazy narrative form, in which the protagonist is always seen obscurely and indirectly, and permits nothing—not even her bare existence—to be verified as fact.

Madam X is a stranger with a shadowy past. She has opened a snack shop on Five Spice Street (五香街), but otherwise holds back from the street’s communal life. She shuts herself indoors to pursue activities variously called “performances,” “research,” or “miracles”; whatever these practices are, they are solitary and admit no clear description. Rumors abound concerning her: that she is a former government official in disgrace, that she exerts an occult influence on the people of the street, that she is having an affair with a Mr. Q under the nose of her complaisant husband. None of this is precisely proved or disproved over the course of the book, which holds itself to a collective, external narrative compiled from the observations, conjectures, and outright fabrications of the prying neighbors. Five-spice powder is a common ingredient in the kitchen, but as narrative it makes a less harmonious mélange; every part of it is contradicted by some other.

Like Yellow Mud Street (黄泥街) in Can Xue’s earlier novella of that title, Five Spice Street is nominally part of a larger city but acts as a closed space. Apart from the initial irruption of Madam X and her family, hardly anyone arrives or leaves. The insular setting might recall the rural villages of Cultural Revolution “scar literature,” though the cruelty and famine that appear naturalistically in that genre, and obliquely in Yellow Mud Street as decay and infestation, are absent here. What persists is a paranoid social structure of spyings and denunciations, meetings in dark rooms, insinuation in every speech. “In our discussions, we used to squeeze together…we lowered our voices, making them fainter than the buzzing of mosquitos. It was as if we weren’t talking at all, just moving our lips. We could only guess what the others were saying… Only the in-group could understand the profound meaning of these movements.” The subject of these meetings is invariably X, who has been branded a social problem in need of solving, a “dissident element,” a “slut,” a “counterfeit,” a “loathsome spotted mosquito” sucking the community’s blood. Yet over the course of the book, very little direct action is taken against her. The longer the vilification goes on, the more it comes to seem the obverse of the fascination—even desire—that so many characters covertly profess for her. “On Five Spice Street we all knew: whenever someone expressed contempt for a certain thing, that thing was what he or she secretly desired.”

Can Xue at age 15 during the Cultural Revolution when she lived with her father.

Yellow Mud Street is often taken as an allegory of life under the Cultural Revolution; certainly its juxtaposition of Maoist slogans with images of vermin and disease earned it heavy censorship on its first publication. Can Xue, who discourages political readings of her work, has described that novella as “not very mature,” incorporating too much of the outside world.⁴ The breakthrough (突围) that she attempted in Five Spice Street was to break free (突出) from the quagmire (or “mud-pit,” 泥潭) of language and culture.4 One way to gloss this would be to say that historical China—the squalid, dissolving landscape of Yellow Mud Street—is no longer her topic, not even allegorically. Five Spice Street places its questions of public and private identity at a more abstract level, and when snippets of historical language do intrude—whether as Cultural Revolution propaganda or Culture Fever’s utopian pronouncements—they are made to play a more general role. When the officious Dr. A says that “in considering problems, one must not look at the surface, but must pierce to the essence with blade-like eyes,” he expresses a recognizably Maoist thought.⁵ Yet it is not only Mao’s but any such overconfident method that founders on X’s basic unknowability. If she has an essence, it is not graspable in the way that Dr. A imagines. What can be known is no more than what the novel shows us, a layering of incongruous surfaces.

Apart from Dr. A, the book offers two representatives of the public world as foils to Madam X. The first is the “much-admired widow,” a matriarch who plays the same authoritarian role as the mothers in Can Xue’s short fiction. The prime mover of Five Spice Street’s public life, she takes it on herself to direct the “struggle” against the “adversary.” Much of the evidence against X comes by way of her “unique powers of observation,” which include breaking into X’s house and opening her mail, and she administers ideological corrections to those who admit a prurient fascination with X, as well as to those who consider the X affair not worth their time. Her invective contradicts itself in the usual way of propaganda against adversaries: on the one hand X is dangerous, an immediate threat to be opposed by all means available; on the other hand X is powerless, negligible, beneath consideration.

The second foil is the actual narrator of the book, who does not immediately emerge as a distinct character since his duty to the collective forbids him to use the first person singular. For the street exclusive of Madam X he writes “we”; when he means himself, he writes “the writer”; after an early scene in which he is attacked for artistic pretensions, he humbles himself to “the stenographer.” His task is to assemble the contradictory accounts of the X affair into what becomes the book’s text, a “precious historical record.” He glosses over difficulties with sheer propagandistic brio: “On our flourishing, colorful street, each resident enjoys full freedom to the best of his ability. Like a duck taking to water, everyone is relaxed and happy. Vehicles full of wonderful foodstuffs roll past…” In his telling, even the sinister nocturnal meetings acquire a nostalgic glow: “Many still sigh and say they wish time could reverse itself—if only it could stop in that moment filled with mysterious conviviality…they wouldn’t mind having their lives cut short by a decade or two.” The writer’s aim is to “draw a diagram of the maze,” “to string these diverse viewpoints together like pearls, bring them into focus, and achieve a static view, like the way the sun—before it sets—grasps the whole of the universe.” Yet he recognizes the impediments to his task; for every question the “answers were maddeningly endless. Where one person saw a wild boar, another saw a dove, and perhaps a third person saw a broom.” Before long he finds himself plaintively asking: “Is Madam X even a real person, or is she a figment of our imaginations?”

The absent center of Yellow Mud Street is one Wang Ziguang, a Godot-like figure of vague promise who was much discussed but never encountered. Madam X is a touch more substantial than this, but only a touch; from beginning to end she remains the unknown entity signaled by her name. The writer and his informants are chary of physical description, preferring to pass immediate judgment, and the profusion of direct quotations hardly provides the intended journalistic grounding since any one account of X will be immediately contradicted by some other. The book’s first public meeting takes place with the simple object of determining her age and looks. She is said to be skinny, as befits so ghostly a figure (and contrasts with the widow’s much-remarked breasts and buttocks), but beyond that nothing is agreed upon, and the disagreement soon provokes physical violence—not for the last time. The writer is left to give an ostentatiously contentless summary of X’s qualities: “skin that’s either smooth or rough, a voice that’s either melodious or wild, and a body that’s either sexy or devoid of sex.” With the same specious precision he calculates that, since her age lies somewhere between twenty-two and fifty, there must be “at least twenty-eight points of view” on the matter.

Can Xue with her son at 6 months, 1979.

In the presence of X vision is a barrier rather than a portal. A letter intercepted by the widow recounts that “The first time Mr. Q looked at X’s face, he saw only one immense continuously flickering saffron-colored eyeball. Then he swooned and couldn’t see a thing. To the very end of the scandal, he never got a good look at Madam X. He didn’t because he couldn’t. When Madam X was in front of him, all he could see was one saffron-colored eyeball.” Even when X’s eyes do not obliterate the rest of her form, they are usually obscured in some way: lacking pupils, or else clouded by tears. Early on it is asserted that “she didn’t look at people with her eyes,” that her eyes “had retired”; though she perceives physical objects, people are obscure to her. When the public intrudes into her house, she complains that oxen are wrecking her research—“There’s always something coming in. Damn it!”—and her husband, who repeatedly serves as mediator, can only mollify her by reducing people to things. One intruder, he says, is “merely a rag drying on the clothesline”; another is a “dust rag…in the wrong place, and that bothered you. I threw it into the garbage.”

Yet with mundane blindness comes otherworldly vision. Madam X’s private activities are thick with mirrors and microscopes, trained on vistas of which the writer can catch only hints: “If you close your eyes, you’ll see the spectacle of spaceships and the Earth colliding”; “a twig poked through a red heart and a blue heart and hanging in midair”; “she concluded that she was standing on a huge, creaking sheet of thin ice.” The sexual affair with Q, if such it is, is conceived by X in purely mystical terms. Unable to see him, she employs a faculty “ten thousand times truer than seeing” to perceive a Q who has little in common with the Q seen by everyone else. In her vision he becomes a “peddler from afar,” wearing a baize overcoat, with eyes of “at least five different colors.”

The writer dismisses these descriptions as “double-talk.” Yet they are one of the few points where the novel approaches the lyric quality of Can Xue’s short fiction. In her stories, women often shut themselves inside houses; Xu Ruhua in “Old Floating Cloud” ends her adulterous affair by blocking her doors and windows and turning into a bundle of dry bamboo, while the nameless “I” of “The Things That Happened to Me in That World” secludes herself for an ecstatic encounter in an imaginary landscape of ice. The glacial scenery of X’s own visions, as well as their ambiguous sexual content, certainly follow from this, but the point of view has changed. Five Spice Street inverts the visionary short fiction by restricting itself to externals, and showing only the reaction to a visionary whose visions are unknowable. Much of the opacity in the stories derives from the characters’ inability to communicate; a barrier stands between them, and only allows them to soliloquize their obsessions at each other. In Five Spice Street, the barrier has contracted to surround X alone. Communication is possible in the public world, though it mostly consists of sloganeering and abuse; but when language encroaches on Madam X’s private sphere it finds itself silenced.

Whatever the true extent of X’s sexuality, the street’s obsession with it testifies to much repressed desire. The most obvious satirical target is the widow, who boasts of keeping herself “pure as jade” although she makes clumsy seduction attempts on both X’s husband and the writer. She vents her jealousy by calling X a “skinny monkey” without the sexuality of a “real woman,” but this does not at all diminish the street’s appetite for an adulterous affair, every detail of which they have invented. Having posited (and confirmed through “high-level telepathy”) that X and Q’s tryst took place in a granary, they spend an entire chapter on competing retellings which all turn out to be opportunities for sloganeering: one character is masculinist, one feminist, a third simply hopes to establish himself as a genius. Others are inspired to action over words. Various sex farces interrupt the main drama, often between comically mismatched parties (an old woman, a young coal worker), at one point drawing the entire street into an outdoor bacchanal, “sweating profusely and breathing hot and heavy like oxen.” To the extent that X notices this, she finds it incomprehensible. “What the hell?” she asks her husband. “Did I ever give a lecture to those guys?” She is the catalyst for every event in the book, but always at a remove; she cannot be affected as others are, for she is not a person as they are.

A different kind of book would have us reject the writer’s narrative, and the communal viewpoint he represents, as simply unreliable. Yet amid all his partiality and conjecture, the writer does display genuine insight: for one, he understands that Madam X cannot be imagined separately from the desires that the street has foisted upon her. She is “an assumption that might not be true—like a tree with massive foliage but shaky roots”; the “only true existence is the illusion, the foggy mist that aroused our enormous interest.” It is only natural, then, that the street’s tactics of surveillance, confrontation, and denunciation get no purchase on her. Only at the end of the book do they hit on an alternate plan, and instead of repressing her begin to acknowledge and even celebrate her. As a means of neutralizing her power, this turns out to be far more effective. In a political context, we would call such a move a co-optation; in a psychoanalytic context, we would call it a cure.

Can Xue at the University of Iowa, 1992

In a late attempt to draw his “diagram of the maze,” the writer hits on the dialectical insight that X and the street are interdependent. “Without Five Spice Street, X would not have existed…We molded her…it was because of X that our good character and our noble sentiments had the chance to be revealed.” Recast as a necessary stage in the street’s historic development, X becomes explicable through rhetoric: “A mother can’t casually abandon her child, even if that child is a rascal or a traitor.” The figure of the mother heralds the most nightmarish moments in Can Xue’s fiction, and the insidious talk of forgiveness sounds much like a dissident’s forced confession. This essentially comic novel dispenses no such grim fate to X, but from this point forward her influence is seen to wane. It becomes possible to imagine her dissolving as she appeared, fading to a symbol and finally vanishing altogether, “returned to the womb.” The first thing to go is the never-sturdy adultery plot, which abruptly resolves through the simple disappearance of both men. X’s husband is said to have left her, while Q sticks himself in the crack of a tree and dries into a insect-like husk. Neither returns; but then, as the writer acknowledges, they were never substantial characters in the first place, “mere shadows—X’s shadows, two parasitic vines.”⁶

As it turns out, the easiest way to integrate Madam X into the community is to hang a slogan on her. The chosen phrase, “the wave of the future,” is conveniently utopian; it acknowledges the fascination that X exerts (“everything she did is something we had been longing to do”) but places her at a safe remove: “what Madam X does and is today is not at all related to real life. It’s an artificial performance… To transplant her style into the context of present life would only create jokes.” The supposed honor of electing her people’s representative has no practical consequences, other than requiring her to turn two somersaults in public and have her picture taken, an imposition she had avoided as a pariah. In her last talk with the writer, she recognizes her incommensurability with the public world: “Her greatest wish was that the people would ‘forget’ her… she had come to understand that she was different from others. She wasn’t a person but only the embodiment of a desire. Because it could never be actualized, this kind of desire could only upset people.” It is a quiet irony that in confessing her lack of personhood, she comes to seem like a recognizable person for the first time.

In her disempowerment, X is driven at last to appeal to the community. When she applies for funds to keep her house from collapsing, her application is treated as an art object, universally praised, and set aside until her wall falls down. Subsequent applications are less comprehensible, “monotonous and dull, absolutely different from her earlier sexual exploits. Who had the patience to watch her doodling.” Fortunately, the “wave of the future” requires little attention for the present. “Let posterity deal with it. Our responsibility is only to provide her with space, protect her work, and leave it for future generations.”

Can Xue and her husband, 2009

The conclusion presents a fable on the dangers of canonization: while a counterculture may thrive on opposition, nothing is more deadly to it than indifference. Historical circumstances were not slow to bear out this lesson; within a few months of the novel’s first publication and the author’s bridge-burning Shanghai speech, the Tiananmen crackdown took place and Culture Fever came to an end. The most immediate changes may have been provoked by authoritarian pressure, but accounts of Chinese literature in the 1990s tend to agree that most of the avant-garde writers either turned to more lucrative realist fiction, or gave up writing altogether, because of their perceived irrelevance in the new mercantile order.⁷ For her part, Can Xue simply continued to write, waiting out a period of obscurity in which Chinese journals rejected her work and many of her stories made their debut in Japanese or English translation. “Lots of them hate me,” she said of Chinese critics in 2001, “or at least they just keep silent, hoping I’ll disappear. No one discusses my works, either because they disagree or don’t understand.” Five Spice Street was not reissued under its present title until 2002.

Notwithstanding the utopian language deployed at the end of this book, it is a story of diminishment and dashed expectations. Yet it concludes with a gentle, even wistful tone, as Madam X walks to the edge of the city and recalls a long-ago sexual encounter that never quite took place. If this unconsummated tryst is indeed what inspired the entire chain of rumor, then we have at last traced it back to its starting point in the imagination, a state of pure potentiality. Can Xue’s own comment on the ending is that “although everybody seems to have failed in the story, I think that in a certain sense they have made it—in their discussions about sex; in their vulgar pursuing; and in their warm imaginations about Madam X.” Warmth lies in the inner world. Having followed the many-sided tale of X’s scandal and rehabilitation, a reader able to rest in the inner world may find that warmth as well.

Paul Kerschen is the author of The Drowned Library. He studied and taught at the University of Iowa and the University of California-Berkeley, and now writes and develops software in California.

1. The quote is from Cheng Yongxin’s editorial note in his anthology Selections of New-Wave Short Stories in China (中国新潮小说选, Shanghai shehui kexueyuan chubanshe, 1989). Lu Tonglin summarizes this and other dismissals in Misogyny, Cultural Nihilism & Oppositional Politics: Contemporary Chinese Experimental Fiction (Stanford University Press, 1995), pp. 77-78.

2. 阳刚之气与文学评论的好时光. The text of this speech was reprinted as an epilogue to the first book-length edition of Five Spice Street (突围表演, Shanghai wenyi chubanshe, 1990), but has not been fully translated into English. I rely on the translations in Tonglin, pp. 102-103, and Xueping Zhong, Masculinity Besieged?: Issues of Modernity and Male Subjectivity in Chinese Literature of the Late Twentieth Century (Duke University Press, 2000), pp. 146-148.

3. 寻根文学 is usually translated as “root-seeking literature.” Jing Wang, High Culture Fever: Politics, Aesthetic and Ideology in Deng’s China (University of California Press, 1996) discusses this slogan as well as 中国文学走向世界, “Chinese literature marching toward the world,” and includes a rare dissenting view by the writer Li Rui: “I did not know if Chinese literature ought to or would march toward the world. Neither did I know if the world is truly in need of Chinese literature as anxiously as what Chinese people wishfully thought it should be.”

4. Interview in 残雪文学观 (Guangxi shifan daxue chubanshe, 2007), p. 36. Here and elsewhere, Annelise Finegan Wasmoen has very kindly shared her glosses and insight on Can Xue’s original wording.

5. Xiaobin Yang, The Chinese Postmodern: Trauma and Irony in Chinese Avant-Garde Fiction (University of Michigan Press, 2002), p. 137.

6. Q’s very name testifies to his lack of independent personhood. The names translated “Madam X” and “Mr. Q” appear in the original as 女士X and 男士Q. While 女士 is a common title for a woman of unspecified age and marital status, the parallel 男士 is not a usual title for a man, and has the effect of making Q seem a second-order creature derived from X. Xiaobin Yang’s translation of the names as “Lady X” and “Gentleman Q” might capture a bit of this sense.

7. For one case study see Kang Liu, “The Short-Lived Avant-Garde: The Transformation of Yu Hua” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 63.1 (2002), pp. 89-117.

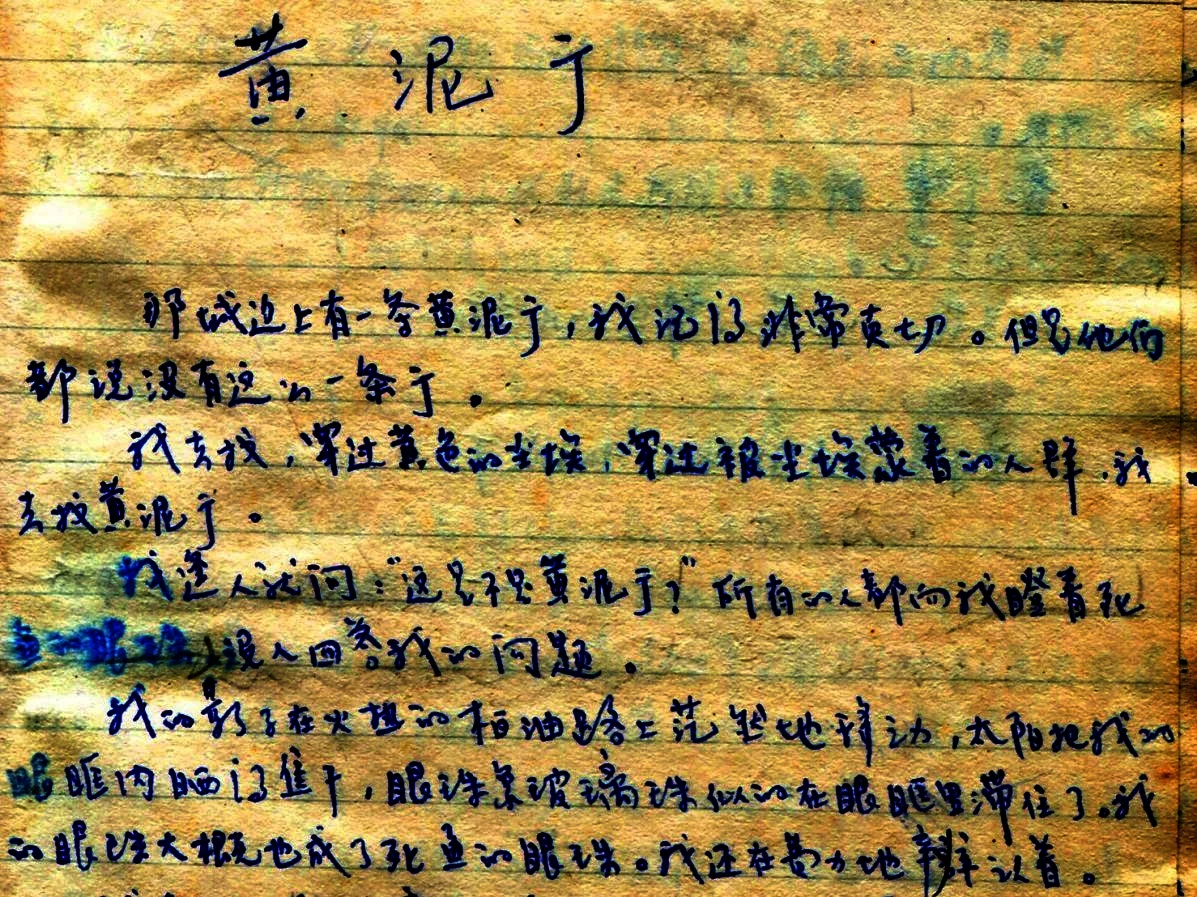

Banner image: Handwritten manuscript sheets from Five Spice Street. Courtesy of the author.