In June 1999, Riccardo Benedettini, writing a thesis on French literature under the supervision of the poet Valerio Magrelli at the University of Pisa, traveled to Switzerland to interview the great Hungarian émigré writer, Ágota Kristóf. This transcript of their conversation is presently one of only a few interviews with Kristóf available in English.

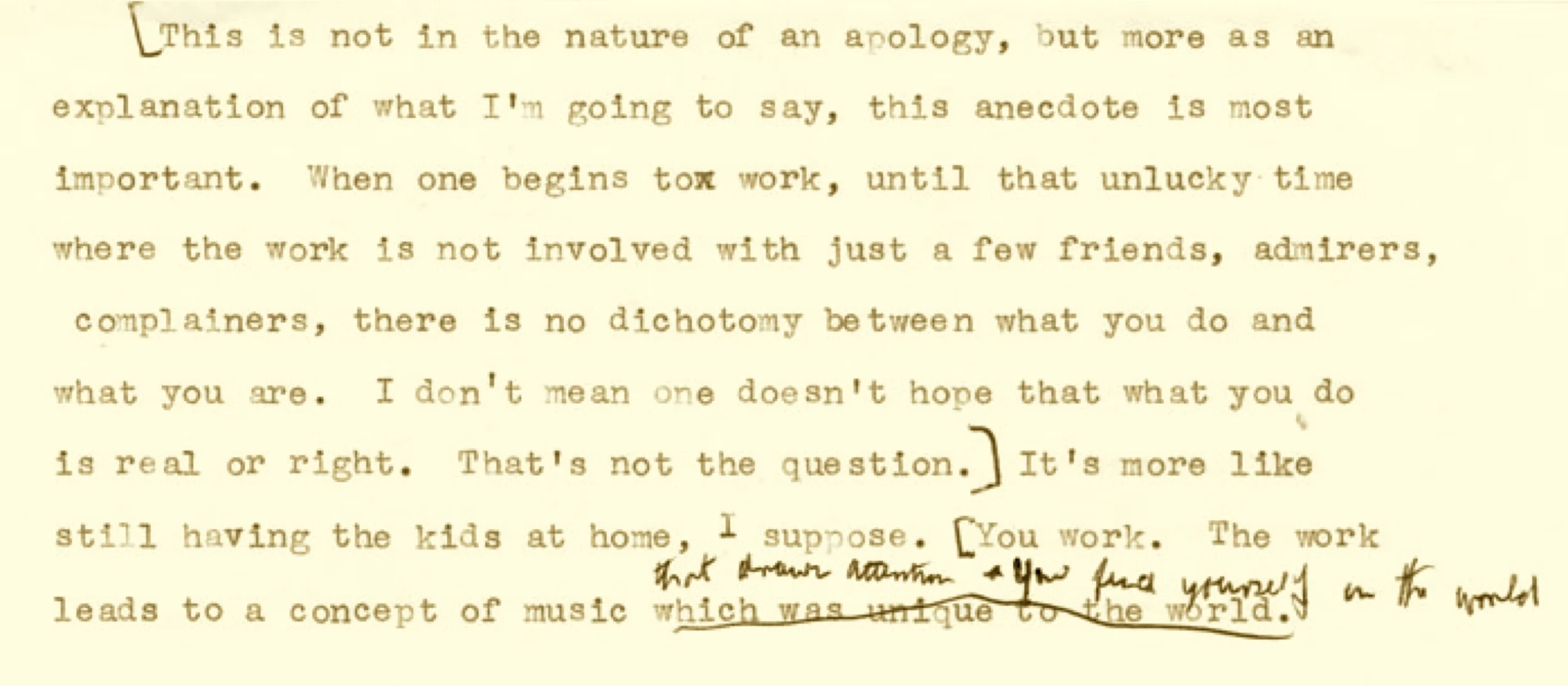

Kristóf did not write in her native Hungarian, but in French, which she painstakingly learned after immigrating to Switzerland when she was twenty-one years old. And as Magrelli, who brought this interview to my attention, puts it, “Kristóf invented a new kind of French.” Unlike Beckett, who kept language itself at arm’s length for the sake of form, she did not experiment with French out of artistic ambition, but in order to live and be understood, not playfully, but with rigor and dedication to correctness—and she did so to devastating effect.

Kristóf fled Hungary on foot and under cover of night with her infant daughter, her husband, and two bags, one containing diapers and the other dictionaries. The family arrived in Austria before settling in Switzerland, where Kristóf found work in a clock factory. Among her fellow workers, many of whom were also exiles, talking was strictly forbidden. Outside the factory, she was mute for a lack of French, and even once had mastered spoken French, she remained effectively illiterate for years. Four of her friends, all Hungarians exiled in Switzerland, committed suicide soon after arriving. Kristóf’s memoir, The Illiterate, which describes these events, is one of the most restrained and concise examples of the genre in all of literature; at just forty-four pages, it portrays Kristóf’s life from childhood in a strange, private, and singular music.

In this remarkable interview, translated here for the first time by Will Heyward, Kristóf answers questions in simple and remarkably direct terms, reminiscent of the brutal sparseness with which she wrote her trilogy, The Notebook, The Proof, and The Third Lie. When asked how or why she created a certain disturbed character or perverse scene, she answers only that she knew that person, or saw that scene. That was just how it was. But her references to what we might call “real life” do not so much highlight the importance of her biography, but how she creates fiction. Even when Kristóf answers “I don’t know,” she reveals something. Kristóf writes; that is her answer. To write is to invent, to amuse, to distract from the life’s many kinds of suffering. As the character Lucas says in The Proof, “There are many sad stories, but nothing is as sad as life” . . .