A feature by Hilary Plum

Hilary Plum: Let’s start with your first novel, The Book of the Sultan’s Seal, just out in English, in Paul Starkey’s wonderful translation. In my work as an editor with Interlink Publishing, I’ve been lucky to be reading and rereading this novel for years, as I acquired it and then saw it through several rounds of editing. This was an exceptionally challenging work for Paul Starkey to translate, since the Arabic undertakes a breadth of linguistic experimentation and intertextual references—to diverse works from the Arabic canon, medieval to present-day—that no other language could really reproduce. Yet somehow, here we are, with this book in our hands. I wonder if you could talk to us, your English-language readers, about the experiments you enacted in the Arabic original, creating a style of narration for the novel that you’ve sometimes called “a contemporary equivalent of ‘middle Arabic’.” What drove you toward this endeavor? And what has it been like for you to see this novel come into being in English?

Youssef Rakha: There were two things I wanted to do with The Seal. The first—and maybe it wasn’t the first when I was writing but now that I’m moving into English, kind of the way you move into a house, I like to think it was the first—is that I wanted, from where I was, in post-millennial Cairo, to be part of the larger conversation that is the contemporary novel. By that I mean quite simply world literature today, which though still dominated by a more or less “Eurocentric” ethos is no longer particularly European, and though rife with death-of-the-novel discourse is actually irrevocably novel-bound . . .

A feature by Damjan Rakonjac

To the extent that posthumous musical works only receive their public “resurrection” following the death of their composer, they always have a built-in cachet. Hearing them feels like something of a miracle. With large works such as Górecki’s Fourth Symphony Tansman Epizody (“Tansman Episodes”), the sense of awed curiosity is only compounded: unlike with a poem or painting, their creator never really got to experience them in the first place. They seem to bridge the putatively unbridgeable chasm between the realms of the living and the dead. What Górecki jotted down in his last moments assumes its aural form only now that his hand has been forever quieted. The Fourth Symphony fits that mold well, surveying the various styles he adopted throughout his career. . .

A feature by Rebecca Lentjes

Ashley’s aversion to plot, to “eventfulness,” makes it nearly impossible to say what Perfect Lives is “about.” It possesses none of the tropes of grand opera (betrayal, love, tuberculosis), only the ordinary themes of the American everyday: money, confusion, forgetfulness, time. “They come to talk, they pass the time. They soothe their thoughts with lemonade.” One can imagine Isolde pondering these words in her mathematical mind, the neighbors sipping lemonade before heading home to watch television.

Most of what we can know about Robert Ashley can be found in Gann’s book, but what we can’t know is to be found in the operas. In Perfect Lives, Ashley’s memories are organized into anecdotes organized into episodes that fade away at the end of the day like the sky in Isolde’s backyard. The lines between the everyday and the infinite, between the known and unknown, blur together like the light and darkness along the horizon . . .

Kronos first met Kaija in the summer of 1984 at the Darmstadt Festival of New Music. I remember it was the same summer that we played Morton Feldman’s big and beautiful String Quartet No. 2 there. And it was the same festival where we met Kevin Volans, the South African composer who would go on to write White Man Sleeps and Hunting:Gathering for Kronos—very important works in our repertoire, and among the first string quartets ever by an African-born composer. So in meeting both Kaija and Kevin, Kronos began two very important relationships that summer . . .

Stig Sæterbakken is one of the most important Scandinavian writers of my generation. His novels in many ways resemble paintings by the Danish artist William Hammershøj: scenes of one or two persons in an otherwise empty room, painted in shades of white, gray, and black. The models often turn their back to the viewer. Occasionally you glimpse a pale face in a mirror. There are sometimes endless corridors, and open doors that lead to a room with more open doors leading to yet another room with yet another open door, and, behind that door, darkness.

A feature by Lydia Davis

Lydia Davis: To start off with, Dan, I have a long question. I’d like to ask you something I’ve been curious about for years, actually. It has to do with your work and your life. You teach full time at the American University of Paris, with all that entails, including directing the University’s Center for Writers and Translators and editing its beautifully produced Cahier Series on translation. In addition, you have, for many years now, been one of four editors in the monumental (and highly labor-intensive) ongoing project of producing a multi-volume selection of Samuel Beckett’s vast correspondence, three fat volumes of which have to date appeared. You regularly give public lectures or take part in conferences on this ongoing project as well as on other subjects as various as Muriel Spark, the Scottish Gothic, translation, Primo Levi, etc. You have written a number of articles on writers including Flann O’Brien, Georges Perec, Thomas Bernhard, to name just a few. You have translated numerous works from the French, and written a study of psychoanalysis and fiction, as well as what I found to be a very engaging and thought-provoking—not to speak of amusing—memoir of your last days of psychoanalysis. As if this were not enough, you are also a writer of fiction, with, now, three novels to your credit, the latest being the imminently forthcoming Emperor of Ice-Cream. You also have a life quite apart from literature, of course—family, friends, dinners, outings to concerts and museums, travel. So, my question is, how do you do it?

A feature by Katy Derbyshire

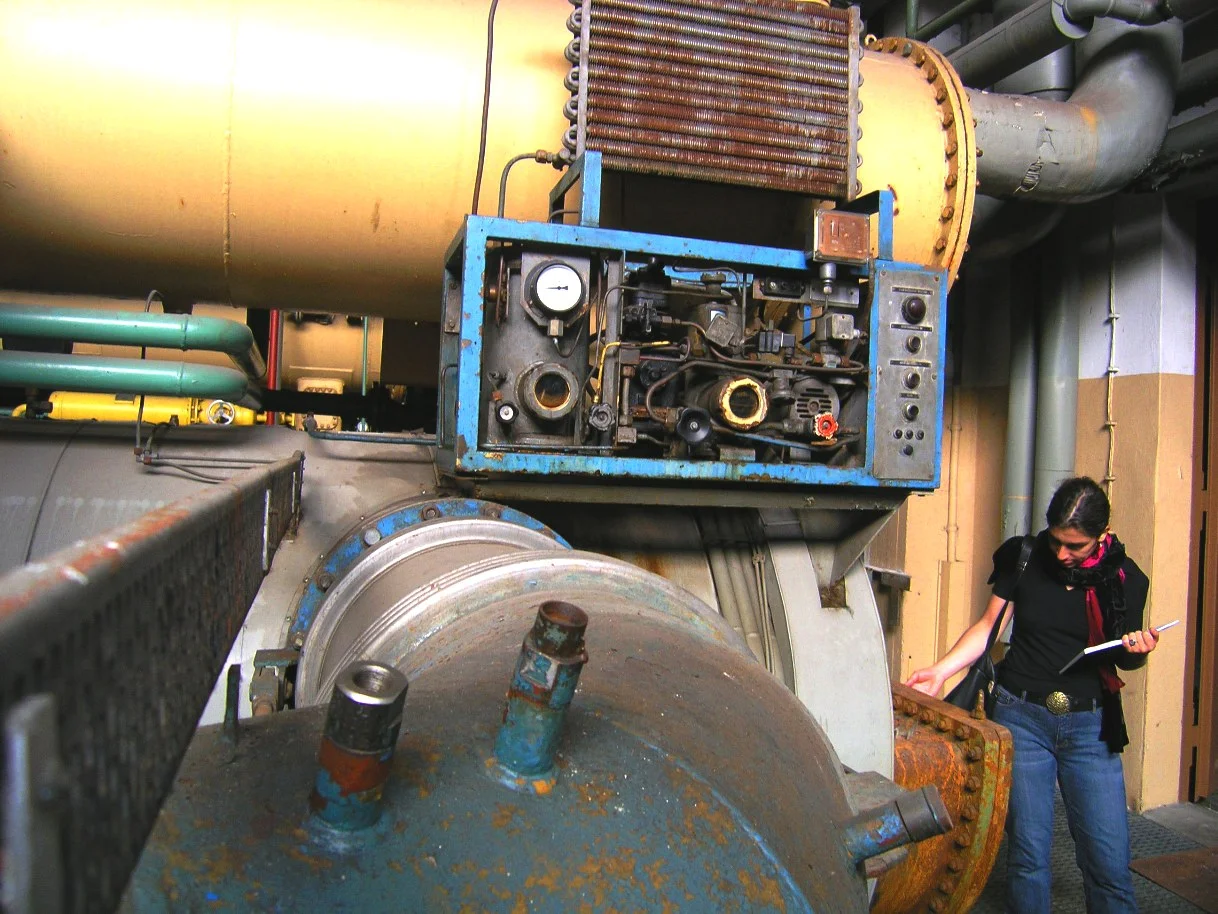

The Berlin novelist Inka Parei has written three books—The Shadow-Boxing Woman, What Darkness Was, and The Cold Centre—all of which I have translated for Seagull Books. Recently, we visited two locations: an absolutely unspectacular, slickly modernized residential building in Berlin-Mitte where Inka once lived—in The Shadow-Boxing Woman it is run down and empty, the book’s protagonist and her neighbor the last tenants before the landlord strips and refurbishes the apartments—and then, a short S-Bahn ride away, the 1970s block built for the Socialist Unity Party’s newspaper Neues Deutschland. These two settings have disappeared and the places themselves have become bland parts of today’s Berlin. As in Parei’s stories, it was less the buildings than the history behind them that ignited our conversation, which continued by email . . .

A feature by Camilla Hoitenga

At this time, she gave me the flute solo Laconisme de l’aile, a piece she had just written in Freiburg, for a Finnish flutist friend of hers, Anne Raitio (now Eirola). I had just been working intensively with Karlheinz Stockhausen on a piece he had revised for me—Amour for flute—and Kaija’s score, by comparison, looked vague, and I remember asking her many questions about what this and that meant and how much time I should take here and there. Eventually, however, I not only played her piece, it became one of the most-performed solos of my repertoire. And I became her “muse” for all subsequent flute pieces!

Galehaut: I am a character.

Violin: Perhaps I am too. I have no physical existence. I am not an object, though I need a certain class of objects—wooden boxes with strings and a bow—to be heard in the real world. I am represented, bodied forth, by these objects, just as you are by a voice, even a silently reading voice. I am not to be identified with the object that renders me, nor with the musician, any more than you are with the voice relating your words, or the reader or actor whose voice this is.

When Kaija Saariaho describes her 1994 composition Graal théâtre as being “for violin and orchestra,” or as a “violin concerto,” we may imagine her to have had in mind a musical instrument in its actuality, including its tuning and its responses, and we may suppose her to have been considering also Gidon Kremer, her destined performer, but she will have been thinking not only of but through these manifest conditions of her work, to me, to an entity whose features are not materials and dimensions, not personality and technique, but sound, and a design for sound, and experiences of that sound through time.

A feature by Jesse Ruddock

Avishai Cohen has been working since he was ten, when his job was to stand on a soap box and play trumpet for a big band. Raised in Tel-Aviv, the youngest of three jazz prodigies in one house, his music is persistently lyrical, often sublime, and intensely playful. Cohen stands out on stage in a way that’s athletic: his lead’s to follow. What the body has to do with the soul can be heard in the tone of his trumpet, that strange precise math of breath and spirit. On Dark Nights, the third and latest album from his trio Triveni—with Omer Avital on bass and drums by Nasheet Waits—Cohen’s tone is clearer than any voice. The songs all go slow but never keep you waiting to find out what they’re trying to mean. This interview took place high above Broadway Avenue in Manhattan, one afternoon before Cohen played three sets through midnight with the Mark Turner Quartet . . .

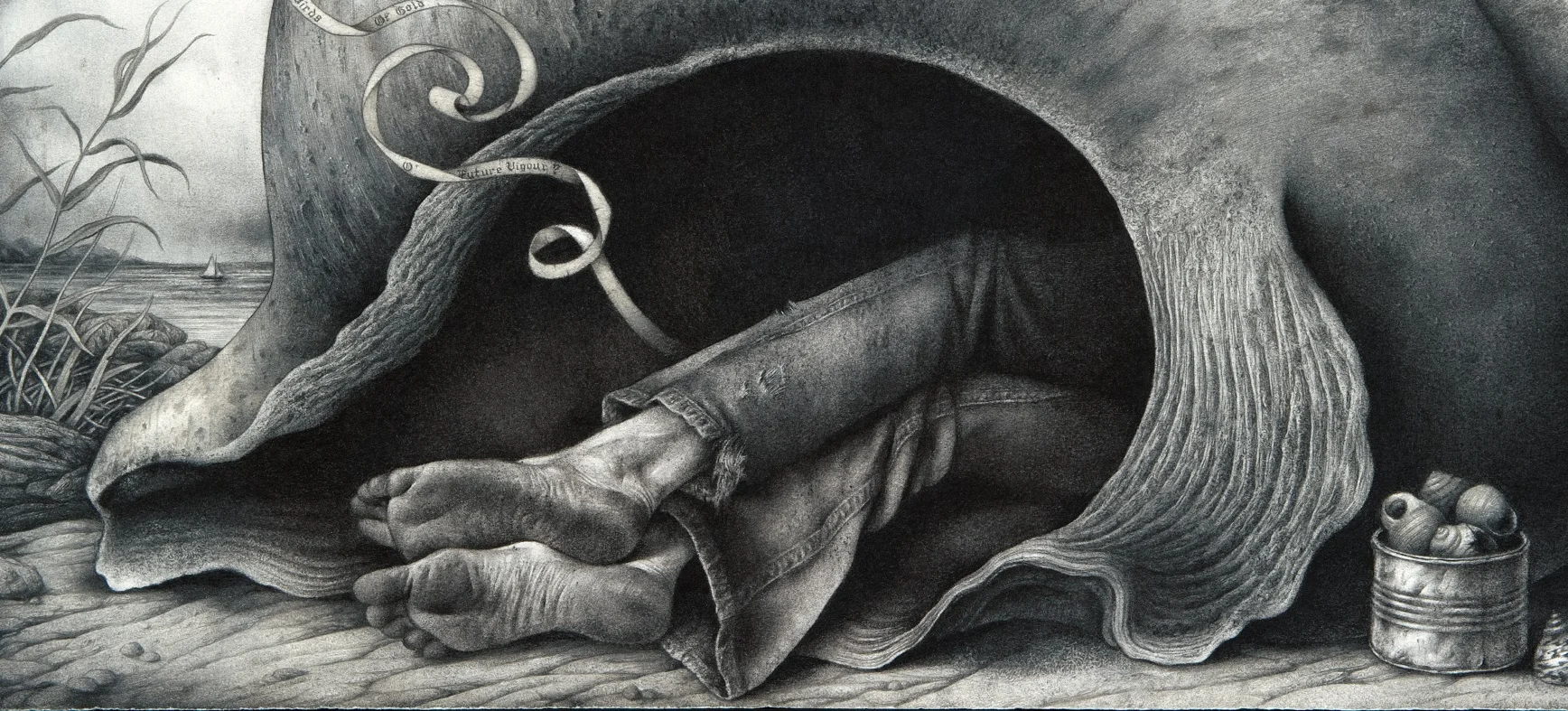

A wonderful sense of being consumed, this is what the Vigeland mausoleum offers its unprepared first-time visitor. But the feeling does not fade through repetition. On the contrary, I’d say. As if the knowledge of what awaits you heightens rather than diminishes this overwhelming sensation. And I guess that’s why so many visitors keep coming back: they want to be devoured again. And again. And again. And isn’t that what drives us, repeatedly, toward art in any form, the dream—however often it leads to disappointment—of being overpowered, shocked, overcome by horror and joy, the stubborn dream of becoming one with the object in question, melting into it, rather than standing at a distance watching it, analyzing it, evaluating it, in other words: the dream of being swallowed, digested, and spat out again, presumably dizzy, definitely shaken, thoroughly and utterly confused, as we re-enter the so-called real world?

A feature by Nell Pach

The previous century saw the explosion of magic realist fiction, texts where daily life and the fantastic filter through each other. The continued development of a genre that steps away from straight realism seems not just likely but, paradoxically, necessary for effective artistic representations of the real and the human. Can Xue's The Last Lover, at once alien and familiar in its casual miracles, its people and things that blink in and out of solid existence, and its radical reconsideration of subjectivity, reads like an inaugural, or at least transformative, text. Call it magic virtual realism. We are perhaps overdue for a literary approach to this new form of human experience. Most of us now live substantial portions of our lives within a cyber-sphere of kaleidoscoping stories, dialogue, and images. We waft in from all parts of the analog world to hold either infinitesimal or prolonged intercourse with people who appear, like us, out of nowhere; we friend them, fight them, not infrequently doubt their existence or aspects thereof. We share moments of feeling we don’t understand, we slide into oblivion or obliviousness with a click. We have come perhaps closer than ever to something that resembles a dreamscape in sober waking life . . .

A feature by Clément Mao-Takacs

Clément Mao-Takacs: I would like to start by clearing up a few clichés that have been said about you. To name a few: You’re from Finland, therefore, you love and get inspired by nature; you are “a fiery volcano beneath ice”; since you live primarily in France, you inevitably subscribe to French music. Can we try to make sense of some of these common preconceptions? Let’s start with the nature-Finland parallel.

Kaija Saariaho: I think there is some truth to the connection between nature and Finland. The country’s population size is so small and nature’s presence there is so important, that it’s impossible to live the kind of urban life you’d have in a big capital—even though some people try desperately to pretend they do. Nature is one thing, but what’s more important is light. Changes in sunlight throughout the year are so drastic that it affects everyone. You can’t escape it when you live there. And because of this experience—which is so physical, we feel it in our body—we have a very special relationship with nature. We have respect for it, we are aware that it’s something larger than us; and also, there are things that are a part of our culture, which can be seen in Finnish epic poems where nature is truly sacred—as is the case for many early cultures. For me, it really comes from this experience of living in the “period of darkness”—there’s a very specific term for this in Finnish: kaamos—all the while having hope for the sunlight to start strengthening again until it is fully restored. Springtime is extremely long, and since the earth has been covered in snow for such an extensive period, there’s a kind of rotting—but pleasant—smell, which gradually gives way to spring vegetation. My relationship with nature isn’t about admiring the aesthetics of a sunset; it’s something much more physical that I carry inside me . . .

A feature by Keenan McCracken

One of contemporary American fiction’s most lauded and prolific novelists, Richard Powers might also be described as the autodidact’s autodidact. An amateur musician and composer, former physicist, and self-taught computer programmer, Powers has become known for his deftness at tracing out the subtle interrelationships between science, art, and politics with a lyrical virtuosity and breadth of intelligence that have elicited comparisons to writers from Melville to Whitman to David Foster Wallace.

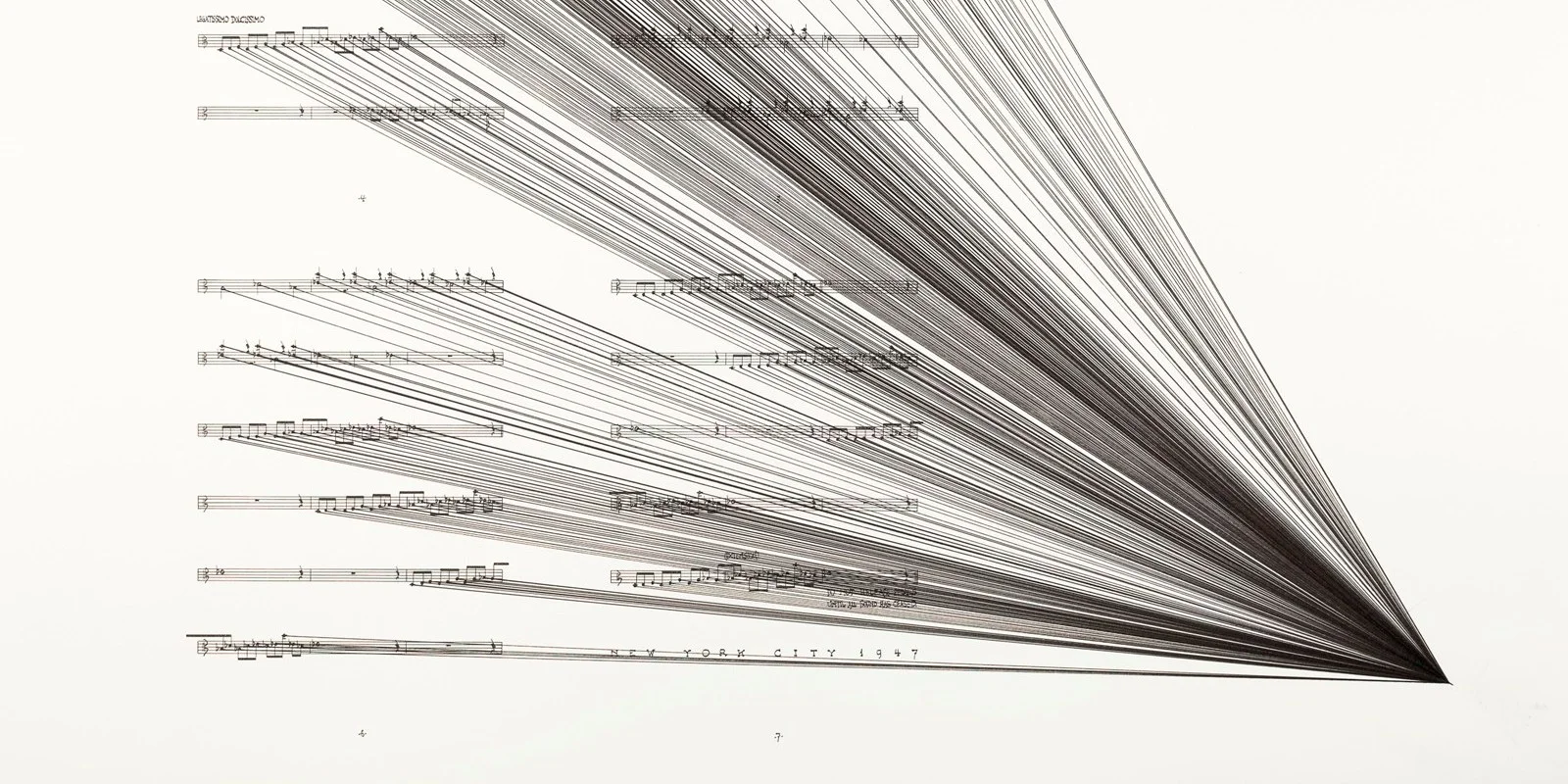

In his most recent novel, Orfeo (2014), Powers examines the post-9/11 political landscape through the life of avant-garde composer turned amateur chemist Peter Els, whose Orphic descent into the underworld of twentieth-century composition and lifelong fascination with patterns lead him to attempt encoding music into the DNA of a living organism. The third of his novels to use music as a centerpiece (after The Time of Our Singing and The Gold Bug Variations), Orfeo is yet more evidence of Powers’s rare gift for articulating the seemingly ineffable qualities of sound, one that is accompanied by a near-encyclopedic knowledge of music history. Incredibly kind and generous, Powers spoke with me via Skype about his new novel and how music factors into his vision . . .

A feature by Christiane Craig

The Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho's oratorio La Passion de Simone has, over this past year, been re-imagined by Saariaho, adapted specifically for conductor Clément Mao-Takacs’ nineteen-piece Secession Orchestra, vocal quartet, and soprano soloist Karen Vourc’h. This smaller cast, under the stage direction of Aleksi Barrière, provides a more direct and unmediated experience of Saariaho’s sound materials. The expansive tonal force of La Passion de Simone’s first production, an oceanic work for full orchestra, choir, and electronics, has been consolidated but not reduced in the chamber version, its sound colors intensified by a microscopic quality of vision that is perhaps better adapted to the piece’s investigation of human, as well as sonic, interiorities . . .

A feature by Daniel Levin Becker

The formal resemblances between Édouard Levé's Works and Georges Perec's I Remember pale away compared to their spiritual perpendicularities: one is an assemblage of purportedly original things that do not yet exist, the other a motley litany of things that once existed but never truly belonged to anyone; one is a series of ideas abandoned at the moment before they crystallize, the other a series of memory-points that exist to be shared and collectively reified. Perec had none of Levé’s impulse toward detachment; the questing in his work was driven by his interest, on some level a desperate one, in the way people could be objectively united in their subjective experiences of time and place, even if they shared neither. Whereas Levé was fascinated by people from a remove, Perec wrote in enormous part to remind himself that he was one of them . . .

A feature by Ian Dreiblatt

Carnegie Hall, May 31, 2014. I watch Arvo Pärt step haltingly into the rear of the auditorium. An usher, thinking him the old man he appears from outside of sound to be, asks if he needs any help, a faint impatience curling the edges of his speech. He shakes his head and proceeds to an aisle, occluded by clusters of Orthodox priests. He navigates among them slowly and without solemnity. Like the people around me, I’m anticipating the concert by remembering things. A procession of them, connected by an invisible logic that feels somehow singular. It’s like mourning. Slow motion up a chain of small bells . . .

A feature by Caio Camargo

Chico Buarque has become a living icon of Brazilian culture. For his seventieth birthday, he was the subject of countless homages and retrospectives, with an admiring piece on nearly every media outlet and birthday greetings and messages from a who’s-who of recording artists and other assorted personalities. The only notably absent voice was from the man himself. From the (relatively rare) interviews he grants, it is clear that he never felt comfortable in the shoes of his legend. Chico seems to make a point to puncture the inflated image, to paint himself as just a guy devoted to his art, who also happens to love soccer and going to the beach. But there is hardly any escape from the fact that he remains, after a decades-spanning career, a defining cultural touchstone. His work bears a great sense of history and politics, a connection to the land of his birth so strong that it is difficult to imagine Chico without Brazil, and impossible to imagine Brazil without Chico . . .

A feature by Declan O’Driscoll

How do you compose? At a piano?

Yes and no. My compositions start their lives with reflections upon paintings, architecture and of course musical possibilities. So, before I really use the keyboard I normally accumulate various sketches that indicate (possibly) movement, energy, pitch areas and outline structures. The keyboard is used later in the process to confirm pitch relationships, note rows and other procedures that help during the composing process. If I ever wrote a piece based only upon my keyboard expertise, the composition would be destined for the trash can.

A feature by Declan O'Driscoll

The following interview was conducted for the occasion of Music & Literature No. 4, which includes some 80 pages of new interviews, graphic scores, poems, appreciations, and other writings on and by the musical duo Maya Homburger and Barry Guy . . .