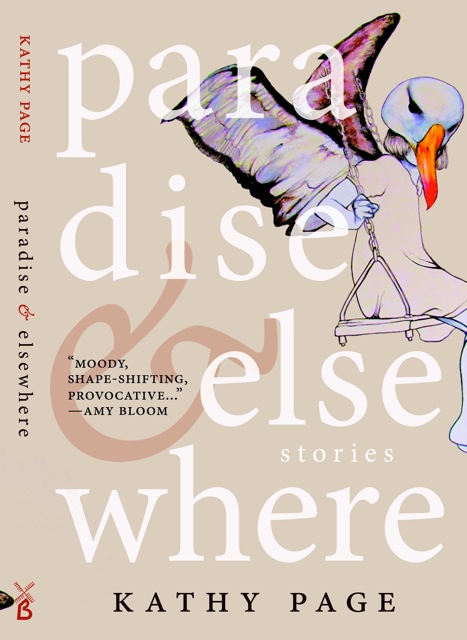

Paradise & Elsewhere

by Kathy Page

(Biblioasis, April 2014)

Reviewed by Dustin Kurtz

Early in Paradise & Elsewhere, her latest short-story collection, Kathy Page places readers in an Edenic oasis of plenitude, communal and iridescent, populated by immortal women—a bubble about to be ruptured by a stumbling heat-stricken outsider. The women of this paradise discuss the intruder:

“Then again, how different was the traveller? . . . We had recognized her as human from the start. Differentness was not the point, some said. It led both ways. Rather, the issue was that she had come from elsewhere and so we did not know her story or intentions.”

Here Page has written a useful gloss of that story, itself called “Of Paradise,” and, indeed, the entire book. In these stories Page gives readers a literature of elsewhere, but one in which difference—or, as above, “differentness”—is not a truth laid bare. Oddity, the fantastic, the cruelty that accompanies them, is not the point. Instead it serves only to highlight a longing, across stories and characters, for a kind of transcendent understanding or (and they amount to the same thing) an escape.

The Canadian author Kathy Page has been compared by critics to Angela Carter, and it’s easy to understand why. In her divisive The Sadeian Woman and the Ideology of Pornography Carter writes:

Myth deals in false universals, to dull the pain of particular circumstances. All archetypes are spurious . . . All the mythic versions of women, from the myth of the redeeming purity of the virgin to that of the healing, reconciliatory mother, are consolatory nonsenses; and consolatory nonsense seems to me a fair definition of myth, anyway. Mother goddesses are just as silly a notion as father gods. If a revival of the myths gives women emotional satisfaction, it does so at the price of obscuring the real conditions of life. This is why they were invented in the first place.

As with Carter, Page enlists the tone of myth and fable to tell nuanced feminist stories, to undermine mythic structures by grounding them in the body. But whereas Carter is using fairy tales to talk about the cruelty and power of fairy tales, for Page the mythic idiom is a means, is incidental.

Her dabbling in what critic John Clute calls fantastika is on full display in this short-story collection, which was published this summer by the Windsor, Canada indie press Biblioasis. There are stories about a selkie, a latter-day gorgon, sexually-transmitted euphoria, even two stories that are frankly if mildly science fictional. About the collection’s inception, Page writes:

I gathered my stories together and began to arrange them. There were two kinds of writing: the regular realistic, contemporary kind of story, and something else rather hard to describe—stories that have a mythical, magical, uncanny, futuristic or fable-like, quality.

The division between extra-ordinary and “realist” fiction is a natural one; the thematic similarities could help the stories more easily discover an appreciative reader. Paradise and Elsewhere bears some resemblance to the prose of Aimee Bender, Mary Caponegro, Shelly or Shirley Jackson and, yes, Angela Carter. The cumulative effect of reading this collection is less wonderment at these fantastic trappings and more a realization of what Page is doing, and how.

The most memorable stories in the book are those that don’t hew too closely to any of those modes she lists—the myth, the fable—but content themselves with being, simply, strange. In her best moments Page fills a story with a subtle rising dread, a migraine you feel coming for page after page. Thus in “Of Paradise” we have the simple perfection of gestures like: “The traveller looked away and stepped out of my embrace. She nodded in the direction of the houses, walked toward them.” All a reader can do is hold on and wait for that dread to either sweep you away or leave you ruined in its wake. If every story in the collection doesn’t run with such dark force, it’s due to Page’s avoidance of more indulgent grotesquerie.

However they were selected, these stories are strung together, nearly every one in the book, by the presence of an intruder: an exterior irritant or catalyst which Page both nourishes and mistrusts. She lets each story swell up from the friction of difference—or “differentness”—then works to rupture it, to divert its force and sanitize it as distance.

Many of the stories interrogate the very idea of travel and, more mundanely, the tourism industry. That can provide an oddly satisfying bit of realism in a book that also contains Borgesian thought-experiments and a furry half-seal stillbirth. Indeed the sharpest joys of the book come when that most prosaic, most bourgeois “differentness” of travel is left stranded in the greater unease of the fantastic, of “something hard to describe.” Rather than release, when Page crashes the tourist economy into the greater subjunctivity of the fantastic (to use a phrase from Delany) the burden of readership grows. In the brief “Lak-ha,” Page writes the fable of a woman who cries herself to death and how the sale of her remains—to a tourist—save her family and by extension an entire culture. The story eventually runs aground on a shingle strewn with modern gew-gaws : “Come inside. We have everything now: television, internet, iPod, cellphone, denim jeans, Barbie doll, same as you.”

It’s a sign of Page’s abilities that this closing line manages to be so deftly sinister. Readers take on the role of moneyed tourists here. The initial request, “come inside,” is not unfamiliar to anyone who’s walked through a bazaar anywhere in the world, and the items listed are only frightening because they’re linked—however indirectly and even through the filigree of myth—to a corpse. But our unease is heightened by collective first-world guilt, and increased by shame at our unease. It’s an impressive way to end a story that carries the burden of a made-up name for a title.

This is not the case with the first story in the collection, “G’Ming”. The story is set in the eponymous village, G’Ming, in an unnamed part of the world. This vagueness is a tool Page uses often, the better to seat her stories in a fairy-tale idiom. The first sentence is a good example of the carefully obscurantive tactics she uses throughout the collection: “The village looks closer to the road than it is and I see them coming from a long way off, their clothes bright white against the mud and the scrub of the plain.” There are no names, only pronouns and the invocation of seeming, of semblance. It’s the classic into-the-dark-wood trope so beloved by Jackson, but inverted so that the first-person narrator is among the hidden watchers. Page goes on to tell the story of a child working to bilk a few coins from the arriving tourists. Unlike “Lak-ha” we are the locals here, and Red Riding Hood is a stingy Western couple in sunglasses. Like that story, however, readers are left with a productive anxiety as a result of the distance Page has established—the wealthy outsiders are complexly sympathetic fools; there is a scene with a benevolent and generous blonde tourist that one hopes, nervously, is not meant to be a stand-in for Page herself; and lastly there is the anxiety about why the fairy-tale idiom is being used at all, about why Page feels the need to plant this town outside of history.

Inexorability, another hallmark of fairy tales, is at the core of perhaps the best story in the book, “Saving Grace.” A camera crew travels through a windswept stretch of country laid waste by austerity measures to report on the rumor of an oracle in a bleak town far from any moneyed urban reassurances. A succession of increasingly unnerving misfortunes befall them. The most memorable scene, however, is a roadside stop for tea:

The track narrowed, grew suddenly muddy, turned sharply to the left, then came to an end between two gates. A rusty estate car was parked facing them. A notice taped to the windscreen said “Tea here,” and behind it a woman sat in the driver’s seat, elbow protruding from the open window. There was a pile of newspapers on the passenger seat. The one the woman was reading, Libby noticed, was parchment-yellow and dated last January.

"I’ll need to get past you,” the woman said. In the back of the car she lit a small stove, decanted water carefully from a plastic container and unwrapped some mugs packed with newspaper in a cardboard box. Her face was pretty in a tense, pointed kind of way: almost a city face. Beneath the bulky jacket, Libby guessed, her body would be small but powerful.

“I’ll need to get past you”: that banal line of dialogue is the hinge around which the entire book swings open. Primed by previous stories and earlier hints of dread within this one we know that all is not well in this northern heath, that doom is hunting the camera crew of “Saving Grace.” And yet Page takes them and us on a literal detour, a pause to buy some tea. The pleasure contained within this moment is not simply the pleasure of the strange, as Delaney discusses—that the possibility of the fantastic in any aspect of the story opens up that possibility in every part of the story, that in a story which contains the inexplicable, tea itself becomes a mystery, a danger. Nor is it just the pleasure, as in “Lak-ha,” of the fantastic abutting the everyday, the thrill of frisson and guilt. There’s also the pleasure of the detail here—not overly descriptive, but with more attention to process than Page usually allows herself. So often the pacing in Page’s stories conforms to her fairy-tale framing: whole seasons pass in a sentence, there are few unnecessary objects in any given story—this shard of pottery, this map, this noise, this man. But here Page indulges in irrelevance, in reality (not simply realism). It is a moment where not every mug, not every coat, is significant.

In an interview Page mentions that much of her work is inspired by actual experiences.

[M]any of the stories in Paradise and Elsewhere originate in journeys I’ve made for personal or professional reasons. I don’t travel frequently, but when I do, it has a powerful and lasting effect on me. I look carefully and think about what I find abroad.

In some stories this point of inspiration is hugely—sometimes unfortunately—obvious. But in “Saving Grace” that intrusion of lived experience is oddly welcome. Of course it may not be the case that Page has ever bought tea from a small woman in a rusting car on a muddy two-track, but the extraneity of the scene makes it feel as though she has, as though Page, sipping her too-cold roadside tea, looked at the cloud-wrapped light reflecting off of wet earth beneath her and thought “ah, I should use this.”

The resulting tableau is not only mundane, it is exterior to the world of the story. It’s not just a pause but a bubble, a weird twist of extra-dimensional geometry that our characters must pass through. The inexorability of fairy tale continues here, but the characters, necessarily thin after only a page of introduction, have now gained a perverse weight. “I’ll need to get past you,” Page writes. This idea of being in another’s way, this clumsy experience, at the very center of what it means to inhabit a body among bodies, is too rare in fiction generally. And yet it crops up throughout Page’s work. It happens in the very first scene of her novel Alphabet, and more than once in her The Story of My Face, a book which as a whole pays great attention to the bodies of its characters.

It’s rewarding to see that her interest in the flesh has been sustained over decades. Page is a British native and wrote her earliest work there, including the four stories in this collection that appeared in her earlier As in Music. She followed this with a career as a counsellor and therapist. That job informs Alphabet—some of her work was done in the prison system—and, to best effect, the last in the collection, “My Fees.” Here Page indulges in something of an ur-story, a generous list of possible conversations borne witness by some type of practitioner of empathy—therapist, sex worker, killer, oracle. It’s a list at once wearying and thrilling. The result reads like nothing so much as a passage from Javier Marias, if less grammatically ambitious:

I see the body beneath its coverings, how the vertebrae in the middle of your spine bear too heavily down on each other. I notice worn hands or smooth ones, bitten nails, the sudden angle of your foot, weak arms, asymmetrical musculature. I know whether there is a void or a fire between your legs, whether you are bleeding, that your throat hurts, your stomach churns. I can tell from the way you sit which parts of your body you will not look at; that you will be disgusted by hair growing through skin or in love with your own slenderness or with the raised scar on your arm. But none of this, not the room itself, neither the listening nor the watching are the reason for the fee.

It is the same once-upon-a-time vagueness we see in her tourism stories, but a superposition of all options rather than the lack of any. The result feels expansive and intimate, which is the great gift of Page’s focus on the flesh: it burdens us with immediate and undeniable affinity with the characters, those being assessed in “My Fees” and those throughout the book

This is also, in part, where a bodily ruination, grotesquerie, generally gain their power. Twisted Carnivalesque bodies deny us that affinity; they betray the comforts of recognition. Unlike Carter, Page doesn’t revel in violence, violation, perversion. And though she sometimes delves into the grotesque—corpses make an occasional appearance, once in a stew—the moments are fleeting and Page herself seems to shy away from them. This hesitancy rises perhaps from a gentleness in Page toward her creations. The grotesque is farcical, but often cruel. Page understands, it’s clear, that violence, cruelty and grotesquerie—transgressions against the body—are at the very center of the fairy tale mode, and she is willing to let her plots carry her there. But she prefers that the violence be done before our narrator arrives at the scene or downstairs, out a window. Our narrator watches it from a remove, and we are even more distanced. Or, in particular with the grotesque, she insists that it be transcendent in nature. In “Low Tide,” most explicitly, a character transforms and takes flight to escape.

These transcendent moments—imagined, failed, witnessed scenes of escape—are among Page’s strongest. It’s simply that they avoid the possible political ferment with which grotesquerie imbues the fairy tale form. The lesson from “Of Paradise” is played out on the bodies of her characters: instead of harnessing the grotesque, this “differentness,” and turning it against the story itself (as in Carter, as in Rabelais) Page is simply more interested in the kinder possibilities of escape.

This is even true in Page’s other work. In Alphabet the most shocking scene of violence against the protagonist happens, again, as our imprisoned protagonist blacks out and only wakes to experience the aftermath. In perhaps the best of Page’s novels—the excellent Frankie Styne and the Silver Man—deformity, in this case a baby with a birth defect, is understood by the central voice in transcendent terms. In The Story of My Face an act of brutal violence against the central character is the impetus for her escape from a strange religious sect. Again and again Page enlists violence and deformity to shift the course of her narrative, like a Taoist drinking a mercury elixir seeking to transcend life, with no interest in the corpse that remains behind.

But maybe Page’s aversion to the bloodthirst her chosen idiom pushes upon her is due to nothing more complex than taste. Nearly every male character in Page’s work—including throughout Paradise—is a preening buffoon. It shouldn’t need mention that the same is true of men in reality as well. For Page, perhaps sex or violence or monstrousness are too inherently ridiculous, and revelling in them is too male, and so she tries to do without.

More than their imagination, more than their compassion or ambiguity or anxieties, it’s that emphasis—distance, not difference—that defines these stories for good or ill. It’s what sets Page apart from a field of feminist fantasists, particularly Angela Carter. Whereas Carter rejects the comforts of myth, treats it as patriarchal structure to be opened wetly by the recursive blade of fairy tale, for Page the fantastic, the mythic, is a means to tell the story of connection and transcendence, of escape. In service of that story she ropes into these odd tales discussion of tourism, of loneliness, of possibility, of tea. Carter beats on iron that we might hear the din; Page, in this remarkable collection, would rather watch the sparks.

Dustin Kurtz is a freelance book marketer and sometime bookseller. You can generally find him online at @theunread, though he doesn’t recommend it.