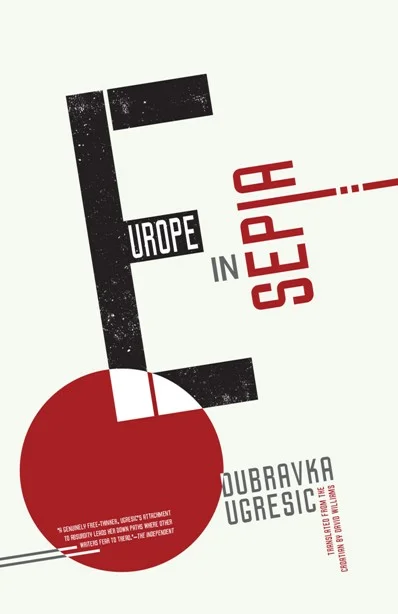

Europe in Sepia

by Dubravka Ugrešić

translated by David Williams

(Open Letter, March 2014)

Reviewed by Madeleine LaRue

Dubravka Ugrešić is a Croatian writer living in Amsterdam, which, as she remarks, tongue firmly in cheek, “is just the sexiest thing ever.” Ugrešić is always the first to subvert her own glamour. Indeed, she has distinguished herself throughout her thirty-year career by refusing to accept the romance, by staring down nostalgia until it splinters apart like her former homeland.

Ugrešić was born in Yugoslavia in 1949 and, despite usually being referred to as “a Croatian writer,” would perhaps better be called Yugoslavian one. During the Yugoslav War of the 1990’s, Ugrešić’s firmly anti-nationalist, anti-war stance made her a target of intense media harassment and a public ostracization campaign. Among the things she was called, “witch” and “traitor” were the most polite. She left Croatia in 1993, terming it “voluntary exile.” It was an effort, she wrote later, “to preserve my right to a literary voice, to defend my writings from the constraints of political, national, ethnic, gender, and other ideological projections.”

Another author might have let the statement end there, eager to cast himself (it is usually himself) as a rebellious hero, the champion of truth and justice in the face of tyranny. Ugrešić has no such illusions. She instinctively attacks self-righteousness, above all in herself. Her explanation of why she left is true, she says, even though she knows it “rings a little phony, like a line from an intellectual soap opera.” Some of that has to do with gender: a man, perhaps, could speak those words with a straight face; men get a “free pass” to “autobiographical kitsch.” For a woman from a minor literature, however, crossing the border means finding yourself in a “literary out-of-nation zone,” which Ugrešić calls the ON-zone.

A Dutch friend of hers assumes that living in the ON-zone must make Ugrešić a highly marketable phenomenon. She has become transnational. Her books, written in Croatian but translated into enough major languages to secure devoted readers around the world, must belong to that utopia of “literature without borders.”

The truth, predictably, is harsher and more interesting than that. There is no such borderless utopia; all books, Ugrešić asserts, have to go through passport control. Furthermore, the few transnational authors that exist are the market’s enemies, not their darlings. Ugrešić’s books, some of the funniest, sharpest, most insightful pieces of cultural criticism being produced today (to say nothing of her beautiful, often heartbreaking novels), deserve to be unqualified successes. Instead, they are literary vagabonds, reliably prompting admiration in those poorer, dreamier sorts of people, and distrust in those with money.

Far from being a trendy utopia, the ON-zone is rather the province of orphans. Despite the prevalence of terms like “transnational literature,” writers like Ugrešić are in constant danger of erasure, not so much because they fail to fit into a tradition of national literature as because they fail to fit into a market niche. For this reason, Ugrešić writes that she feels great sympathy with other types of “losers”—idealists, maladjusted underground men and women, translators—who are so frequently forced into invisibility. Writers, though, seem to have it particularly hard: at least “translating, even from a small language, is still considered a profession. But writing in a small language, from a literary out-of-nation zone, now that is not a profession—that is a diagnosis.”

Europe in Sepia, Ugrešić’s latest book to appear in English, is a diagnosis, too. The twenty-three essays in the collection investigate various forms of crisis (“crisssisss,” she writes, “the word buzzes among the old theatre walls like a pesky fly”), becoming a catalogue of the madnesses, ironies, and tragedies of the global age. Whether discussing politics and culture, nostalgia and memory, or women in literature, Ugrešić proves that she is not only an excellent prose stylist, but a rigorous thinker as well. With a novelist’s talent for anecdotal illustration, she exposes the symptoms and causes of the current western malaise, wasting no time in condemning those who perpetuate suffering in the name of progress or profit. Like most writers worth listening to, Ugrešić has a great deal of intelligence and very little traditional power. Her observations are therefore tinged with “the suspect joy of a failed suicide,” that comical despair one finds in a Dostoevskian hero who feels pain a little too sharply, whose sense of hope is as unwarranted as it is unshakable.

The essays are divided into three broad chapters: the first, “Europe in Sepia,” is the most overtly political, taking on nationalism, nostalgia, the former Yugoslavia and contemporary Croatia. The second, “My Own Little Mission,” turns away from grand narratives to focus on individual, bizarre features of our world: the vandalism unleashed upon a certain statue’s umbrella, for example, or the “eco-friendly” practice of liquefying the dead. The five essays in the book’s final chapter, “Endangered Species,” are perhaps the most personal in the collection. They deal with the writer’s life—or what has become of it in the age of “marketing angles”—with women, and with the out-of-nation zone. In fact, though I described these essays as “personal,” the adjective is misleading. The personal, as we know, is political, and the issues Ugrešić approaches from within her own life — the erasure of women from literature and history, the lack of a women’s canon (and the difficulty of constructing such a canon in the first place), the daily instances of professional discrimination—remain deeply and terribly relevant, not only to women, and certainly not only to writing women.

Though each chapter hangs together only loosely, Europe in Sepia as a whole is remarkably cohesive. An idea sounded in one essay is sure to echo in another, reinforcing each individual theme and emphasizing its connection to the others. Yugoslavian nostalgia, pop culture fads, and the fate of the writer are, to Ugrešić’s mind, inextricably linked—by their relevance, perhaps, both to her own life and to what Europe has become today. These issues have shaped her writing for decades; their importance and interdependence endure, so that very often, an essay that begins with politics will end with Twitter, and another that begins with Wittgenstein will end with politics. Each category of concern permeates the others, and the distinctions among them are always temporary.

At the beginning of book’s first essay, “Nostalgia,” it is 2011, and Ugrešić is in New York. Attempting to find her way to Zuccotti Park, the site of the Occupy Wall Street camp, she approaches a tourist information kiosk, and asks, “goofily,” “Excuse me, where’s the, ah . . . revolution?”

The question contains all the complex charm of Ugrešić’s way of being in the world: like her, it is straightforward, yet ironic; rebellious, yet slightly abashed. We sense her awareness that the vocabulary she grew up on, and still identifies with, has not aged well, that it now rings “goofily.” The word “revolution,” like the stirring opening lines of The Internationale, “Arise, damned of the earth,” belonged to an ideology of infinite promise, to the rhetoric of a “brighter future.” Yugoslavia, as Ugrešić describes it, was brimming with optimism. And then the Berlin Wall fell, and two years later Yugoslavia fell, and as of some point after that, Europe—or at least Central Europe—has no bright future. Europe has eyes only for the past. Nostalgia was a coping mechanism and an avoidance strategy.

The lack of a European future manifests itself as both a psychological and a visual problem. While the nuances of the psychological conundrum take many pages to explore, a single striking anecdote manages to convey the absurdity and sadness of the visual hurt. “Lately I’ve caught myself turning the faces and hues of Central Europe into photographs,” Ugrešić writes in the opening lines of her collection’s eponymous essay,

an automatic click on an internal camera and I’m done. A second later an iPhone program whirrs inside me: import—effects—sepia—done. It’s as if the surrounding reality is a screen, stuck to my hand an invisible remote with three options: past, present, future. But only one of them works: past, sepia.

The confession conveys great melancholy, but also exasperation. On the surface, it is an exasperation with technology—no doubt many of us have found our minds colonized by iPhone apps—and behind it lurks the deeper fear that Europe’s depression is the result of a defective imagination. Central Europeans, Ugrešić argues, have given up. They don’t garden, because “gardening is a belief in the future,” they don’t design anything, preferring to sell cheap souvenirs instead, and they don’t write anything. “We’ve never had, nor will we ever have, a Joyce or a Beckett,” Ugrešić states. “Do you know why? Because Vladimir and Estragon—that’s us . . . [W]e’re artists when it comes to waiting.”

These artists represent one side of the Europe’s Janus-faced struggle: apathy and despair. Ugrešić writes movingly, though not always uncritically, of these people who were cheated out of the “bright future” that had been promised to them. She herself still instinctively identifies with them. But there are others in Europe who have been cheated as well, and their reaction is the other side of the difficult coin: an intense but directionless rage. This was expressed in recent years by the teenage rioters who took to the streets of London in 2011, “smashing shop windows and making their grab for street wear and electronics. Expensive mobile phones apparently topped their consumer desires, a detail that disappointed many commentators (If only they’d stolen bread and milk we’d understand!).” Ugrešić herself does not dwell on the legitimacy of these “consumer desires,” but instead draws our attention to the sinister economic circumstances that foster them: “The devastating fact is that the majority of the young English rioters were barely literate.” With no access to higher education and high rates of incarceration and teen pregnancy, these youths too have had their future stolen from them—and by whom? That is another problem that comes with illiteracy, Ugrešić diagnoses: “they don’t know who their real enemy is anymore.”

If Ugrešić knows anything, it is who her enemies are. Literature has taught her well: she writes of growing up on Maxim Gorki’s tale of the young man Danko, who leads a group of terrified people to safety only to die when “some imbecile” steps on his still-bleeding heart. “An unproductive affinity for dreamers who use their hearts as batteries has followed me unfailingly ever since,” she writes. Her loyalties are clear: she is on the side of the weak and naive, against the hateful and arrogant, no matter what scale they operate on. She is therefore staunchly anti-capitalist. Throughout Europe in Sepia, she denounces the systematic failures of capitalism, exposing the invisible hand that is tightening around our throats. “Statistics suggest that our annual spending on cosmetics is enough to end global hunger,” she muses, “yet the question remains as to who’s willing to give up their face cream for a noble cause. No one, I suspect. I wouldn’t either. In any case,” she adds sharply, and rightly, “let the men first give up their weapons, much more is spent on them.”

Her critique of capitalism even prompts her to reflect on the opinions that lead to her exile from Croatia over twenty years ago: “I opposed the war, when I should have accepted the thesis that war is just business, a way to make money by other means.” Perhaps there is even a touch of nostalgia in her analysis; it is surely less depressing to fight a war based on ideology than one based on money and abstract crises. The former kind, after all, can be won.

Most of us cannot choose our battles—history chooses them for us, and history is unkind. If an occasional bitterness creeps into Ugrešić’s words, we should remember that this bitterness is justified. Ugrešić is an idealist and a writer, and is therefore cursed to see the world simultaneously as it could be, and as it actually is. She is not alone in despairing how short of the ideal the reality falls, nor in succumbing to a bleak mood. Indeed, her description of the idealist’s sadness is all too familiar: “It’s the suffocating sadness that comes from a momentary glimmer of hope that all is not lost, that, for fuck’s sake, all can’t be lost, and the realization that this record has been stuck for years, that all is really lost . . .”

Ugrešić’s moments of gloom may strike certain readers as being quintessentially Slavic. If so, her readers can take comfort in knowing that her sense of humor, too, is every bit as Slavic. Witty, ironic, self-deprecating, and surprising, Ugrešić’s humor is as crucial to her writing as her indictments. Like the best of her comic predecessors, including Gogol and Daniil Kharms, she can be variously victim, spectator, and executioner, secure in the knowledge that the gallows are always good for a laugh. Many of the most hilarious scenes in Europe in Sepia play on this supposed Slavic morbidity and incomprehensibility. In one especially memorable episode, Ugrešić’s name, Dubravka, is so distorted by a Starbucks barista (who renders it “Dwbra”), that she decides to choose a Starbucks pseudonym. No sooner has she settled on “Jenny” then the plan goes awry in Dublin, when a chipper barista chats with her at the counter, repeating her false name ad nauseam.

“How are we today, Jenny?”

“Good, thanks.”

“It’s grand to be good, is it not, Jenny . . .”

[ . . . ]

“Here’s your coffee, Jenny.”

“Thanks,” I said, taking a seat at one of the high chairs at the bar.

“What are your plans for the day, Jenny?” the kid asked.

“To hang myself . . .”

“Good choice, Jenny . . .” he replied, his tone of voice unchanged, and served the next customer.

The episode comes from “What Is an Author Made Of?”, one of the best essays in the collection. It deals with the two topics dearest to Ugrešić’s heart, literature and Yugoslavia. For this reason, perhaps, it is one of her most poignant. In the section dealing with the author’s nationality, she relates the story of the Yugoslav national anthem, “Hey, Slavs,” whose lyrics she could never remember. They have to do with a collective voice that swears the Slavs will endure for the ages, despite threats both spiritual and profane, and with a stone-shattering earthquake. “In this climatic drama the Slavs stand as resolutely as cliff faces,” Ugrešić explains, “like extras in a cinematic biblical spectacle. But filming was wrapped up long ago and everyone’s gone home, apart from the Slavs who are still standing there, probably waiting for someone to tell them they’re also free to go.” The poor wretch who ends up with a curse on his head, she adds, could just be the “extra who first remembers to go home.”

Why does this story come up in an essay largely about literature and the author? Because this is precisely what writing is for Ugrešić: an attempt to free herself, an attempt to go home. She did not leave her country, in the end; her country left her, as soon as it stomped on the heart of its “bright future” and handed her a Croatian passport. Ugrešić herself is the “traitor” who does not want to live her life in on a cliff face. She is, as she proclaims, with the losers.

One of her most beloved losers, and our constant companion throughout Europe in Sepia, is the twentieth-century Russian and Soviet writer Yuri Olesha, whose novel Envy provides each chapter’s epigraph. Yuri Olesha was one of those who used his heart as a battery. At one point, Ugrešić quotes a scene from Envy, in which one character (a trickster) enjoins another (a loser) to “[l]eave a scar on history’s ugly face. Shine, damn it! They aren’t going to let you in anyway. Don’t give up without a fight!” Dubravka Ugrešić, it seems, has taken this all to heart, with equal parts sincerity and irony: she shines, and she fights, even though “they” are clearly not going to let her in—or rather, out, out of the purgatorial out-of-nation zone.

But the ON-zone is not necessarily worse than the alternative; we are always struggling, Ugrešić writes, between “equally bad choices,” and our resistance will inevitably break down. Bitterness will set in, along with laziness and envy. These are hazards of life in the ON-zone, or, more likely, of life in general. The one advantage of the ON-zone is its tired brand of endurance: with so many quiet rebels and discontented dreams to populate it, the zone is fragile but indestructible. And given our perpetual state of crisis, the zone will only grow, its ranks swelling with the disenfranchised. Europe in Sepia, these dispatches from the ON-zone’s most important citizen, may well prove to be a survival manual.

Dubravka Ugrešić has been been given a voice in English by a number of highly talented translators. Perhaps the greatest attestation to their talent is Ugrešić’s remarkable consistency in rhythm and tone. David Williams, who translated Europe in Sepia as well as 2011’s Karaoke Culture, admirably conveys the author’s urgency and humor. While Ugrešić’s own English is practically flawless, the fact that she continues to write in Croatian and trust her international voice to her translators demonstrates, at least in my eyes, not only a kind of literary generosity, but a solidarity toward those members of the ON-zone who, like her, write and revolt in a minor language.

Madeleine LaRue is Social Media Manager for Music & Literature. Her criticism has appeared in The Quarterly Conversation, Tweed's, and Asymptote. She lives in Berlin.