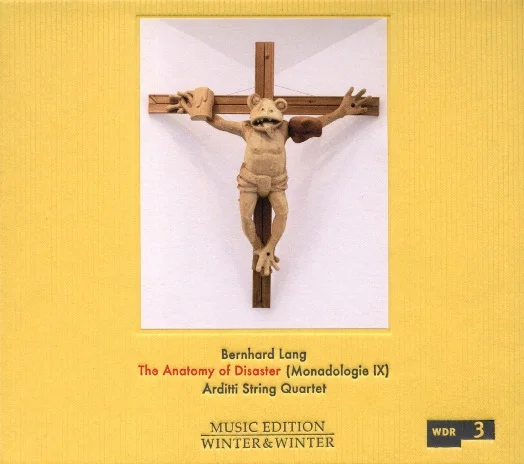

The Anatomy of Disaster (Monadologie IX)

by Bernhard Lang

Arditti Quartet

(Winter & Winter, April 2014)

Reviewed by Tim Rutherford-Johnson

The Anatomy of Disaster (Monadologie IX), written in 2010 by Austrian composer Bernhard Lang, begins like a broken machine. Not one of György Ligeti’s delicately collapsing clockworks or the softly glitching CDs of German electronica group Oval, but a fast, heavy, gunning engine, flailing wildly and dangerously.

But not fatally, because the music quickly takes on a chaotic shape of its own. Fragments turn into components. A hiccuping, short–long rhythm metamorphoses into a motif. The thick texture turns out to be comprised of thinner, overlapping layers. And amongst all the dissonances there are sudden glimpses, baffling at first, of the harmonies of a much older language. Moreover, it becomes clear that some sort of process is at work, even if its mechanisms cannot easily be unraveled. Somehow the music balances layers of looping and quasi-looping materials in unpredictable but still coherent relation.

The piece has its origins in Joseph Haydn’s The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross, first composed for orchestra in 1786 and arranged for string quartet the following year (there are also later arrangements for chorus and orchestra, and for piano). It was commissioned by the priest Padre José Sáenz de Santa María for the church of Santa Cueva in Cádiz, Spain, ostensibly as musical accompaniment for one of the Good Friday rituals. However, there was a second purpose: Padre José had suddenly and unexpectedly inherited a fortune and, bound by a vow of poverty, decided to spend it on his little church. Haydn had recently been freed from his exclusive contract to the Esterházy court, and the opportunity to commission the most acclaimed composer in Europe proved too good for Padre José to pass up. (Later he also commissioned three paintings from Goya.)

As to its liturgical function, the music was written for a Good Friday devotion that originated in 17th-century Peru, in which Christ’s seven last utterances (compiled from the Gospels of Matthew, Luke, and John) are recited, interspersed with extended periods of meditation or prayer. Adapting the idea in grand fashion, Padre José asked Haydn for seven pieces of orchestral music for each of the meditations, plus an introduction and a concluding evocation of the earthquake that the Gospels record at the moment of Christ’s death.

The unique character of Seven Last Words comes from this liturgical role. Each meditation calls for music that is slow and contemplative. Although there is an underlying program, until the very end it is without drama or significant incident. None of the usual qualities in which Haydn’s music traded—wit, contrast, dance—were appropriate. And yet the function of the piece necessitated more than an hour’s worth of music, a tall order even Haydn admitted to struggling with.

I note all this because The Anatomy of Disaster is so intimately engaged with The Seven Last Words that it makes little sense to speak of one without the other. It shares the same form and proportions. It is written for string quartet, like Haydn’s 1787 arrangement. And most significantly, each meditation begins with a quotation from Haydn’s original. (Lang makes the link explicit in his titles for the nine movements.) These are all distorted in some way, in terms of register, rhythm or some other parameter, but once you start to spot them they’re all identifiable. The moments only last a few seconds each—a few more if we count the aura that they cast on the music that immediately follows—but they frame the piece as something other than abstract avant-gardism.

The first meditation, “Pater, dimitte illis; non enim sciunt, quid faciunt,” provides a good example of how the work sounds. It begins with a pseudo-quotation of Haydn’s second bar, six static chords played by the lower three instruments, with a descending arpeggio played above them by the first violin. This Lang transforms into a high register halo of uneven pulses (but retaining the same harmonic outline), with a faint wisp of violin even higher over the top. There is then an abrupt shift to the middle register and different material, harmonically more dense and harder to relate to Haydn’s original. The instruments play in stratified layers, sometimes coming together, sometimes pulling apart. The rhythms are fast and jagged, played with a biting tone. Nevertheless, the contours of individual parts can be heard, and different elements drift in and out of the foreground: a sustained single note, for example, or an occasional moment of Bartókian melody. Seven minutes in there is another abrupt change. What has until now been highly dynamic, relentlessly fast, almost aggressive music is suddenly replaced by another hushed, static harmony, this time colored by a limping rhythm and spots of pizzicato. There is surely something of Haydn in here too, but it is now hidden between layers of material, compressed and folded in on themselves like dough.

The music of our time has a special relationship to the past. It goes beyond a “po-mo” play with signs, although it is indebted to postmodernism for unlocking that particular door. It goes beyond even the “hauntological” approach inspired by Derrida’s Specters of Marx. It is instead a sort of possession, like a benign demon or virus. It can be heard in Michael Finnissy’s piano “transcriptions,” in which a historical original is freely translated into the dialect of the modern day. Or, to take another, very different, example, the music of Carl Stone, in which samples from one piece of music are digitally stretched over the skeleton of another, a process the composer refers to as “injection moulding.”

Almost all of the works in the Monadologie series draw upon music by other composers, from Richard Strauss to Bob Dylan. Lang has even used Seven Last Words before, in Monadologie V for piano (2008-09). Each work is composed using much the same procedure. Like Stone’s injection moulding, Lang’s process is almost wholly automated. First, an existing piece is chosen. Then a small number of “cells,” each just a few seconds or shorter, are extracted. Using software written by Lang, these cells are then processed to create indefinitely long self-generative sequences of music. Inspired by Stephen Wolfram’s writings on cellular automata in A New Kind of Science (think John Horton Conway’s “Game of Life”), the software applies a small number of rules prompting a stream of endlessly changing iterations of the original cell. The starting parameters are adjustable, but the underlying software and the principles upon which it is constructed are the same for every work in the series. Once the computer has generated the music, Lang orchestrates it, intervening only to correct any moments of non-idiomatic instrumental writing.

The disaster of Lang’s title is related to this process: he refers to some of his software algorithms as “disaster sequences,” in which the automata destroy their own vitality and collapse into what Gilles Deleuze would call “dead repetition.” All seven meditations are constructed around such a sequence. Yet it’s hard not to make a more programmatic reading of the word. What was the Crucifixion, after all, if not a disaster of immense proportions? Lang seems to be pointing not only towards Haydn’s work, but in some sense to the inspiration behind it. Yet this is not a spiritually evocative work; so what is the precise nature of the relationship?

Inspired by the composer’s own descriptions, Lang’s music attracts a lot of philosophical commentary. Deleuze is a frequent touchstone; in the Monadologie works so too is Gottfried Leibniz. In a recent article, published in the new music journal Tempo, Christine Dysers writes that “By using short fragments of pre-existing music as a starting point for a new loop-based composition, the opportunity of exploring other states of these musical monads arises. The pieces of the Monadologie series hence not only tend to question the identity of the pre-existing scores on which they are based, but also investigate their future possibilities.” Which is all well and good, but in spite of all this philosophical ornamentation, is there anything here that couldn’t also be said of The Bomb Squad’s productions for hip-hop group Public Enemy?

One difference lies in those computer processes, which give Lang’s music its dissonant, rhythmically unstable, distinctly non-pop character. But more important is the classical tradition within which Lang at least nominally still works. The historical samples in The Bomb Squad’s beats construct an assertive black identity that works in concert with the lyrics of Chuck D and Flava Flav. Lang’s obsession—like that of so many of his peers—is with history as a burden or a responsibility. His music performs a more rigorous critique, but it betrays a cautious approach, too. Lang is delighted to observe and mechanistically sift through the materials of our past, and yet he is reluctant to intervene directly in their manipulation or interpretation. Like Christ, or Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, the music can only watch the disaster unfold around it, crucial to its staging but utterly passive in its response. Do I like it? The ideas are elegant, certainly. And I’m attracted to the conceptual dimension uniting all the Monadologie works. But at the same time, there is an awful lot of music here for Lang not to take up a position of one sort or another. A little more of The Bomb Squad’s cultural self-confidence wouldn’t hurt.

A final word on the performers. The Ardittis are still the go-to ensemble for this sort of repertory. Yet with the emergence in the last few years of quartets like the JACK, Diotima, and Bozzini, one wonders for how long they will remain so; the Ardittis’ precise, crisp, clinical style almost seems to belong to another age now, that of Ferneyhough’s Second String Quartet, Nono’s Fragmente-stille, an Diotima, and Lachenmann’s Gran torso. Lang is a composer of a younger, more fluid time—his work sits between the spaces of the concert hall, club, and gallery in a way that Ferneyhough or Lachenmann certainly don’t. The playing appears technically faultless, but for all the allusions and contextual dimensions, the work comes across as rather dry. The Arditti Quartet’s service to contemporary music is second to none, but theirs is not the only way; if there is more life be had in Lang’s intellectually intriguing piece, it will be for others to bring it out.

Tim Rutherford-Johnson writes and blogs about new music. He is the editor of the Oxford Dictionary of Music and is currently preparing a book on music since 1989 for University of California Press. He lives in London.