Any good adaptation must be, in part, a meditation on form. A film can do things a novel can't, and vice versa; to successfully move between media, one must have some sense of what the medium can and cannot do. A naïve adaptation runs the risk of deboning its original without offering any compensation.

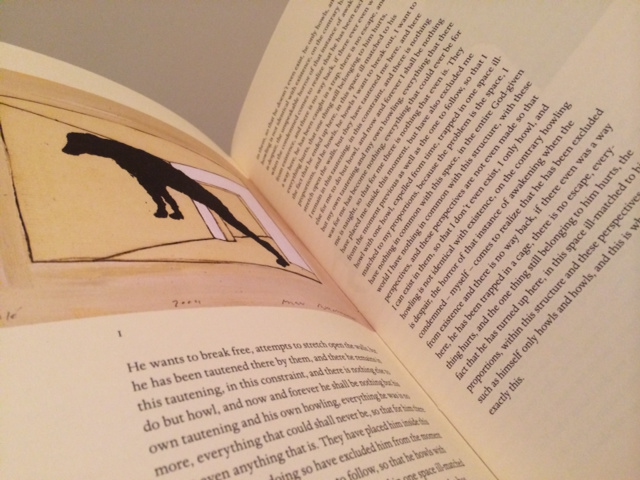

László Krasznahorkai’s Animalinside, published by New Directions in collaboration with Sylph Editions’ Cahiers Series, is, in itself, already an adaptation. Or, rather, it captures a dynamic process of adaptation, in which a writer (Krasznahorkai) produces a text in response to an image, which text then inspires the artist (Man Neumann) to produce further images, which images in turn spawn further texts. “I had given [Krasznahorkai] a drawing once in which he recognised himself,” Neumann said in a recent interview in The White Review. “That’s another example for how an image can be read without a text being written into it. Our collaboration was supposed to proceed from this drawing. He had written a text, which he’d translated somewhat into German. I understood right away what it was about, and we agreed that I’d make a drawing. He gave me the text, and we thought about a continuous passing back and forth of drawings and text. The next day, I called him up and said László, I have eight already. And he said, I already have seven.”

In each of the fourteen paintings appears one or two or three dogs straining on its hind legs, a tense, armless silhouette, pitched up and over the ground. This archetype of struggle gives form to the roving destructive force Krasznahorkai personifies in his mesmerizingly circular prose, just as the prose gives resonance to the image. The texts caption the images and the images depict the text: they are, in a way, equivalent, and yet they are in no way redundant.

Recently, the Slovakian choreographer Jaroslav Viňarský adapted Krasznahorkai’s novella for dance. Created and premiered in Slovakia, Viňarský presented Animalinside at La MaMa this January in New York, one of the hundreds of dance performances that take place every January during APAP (Association of Performing Arts Presenters), a conference in which national and international presenters come to New York to find work to program. The performance embodies the modes of existence the text describes, and yet does so within its own aesthetic parameters, with its own aesthetic integrity. At its best, the performance builds upon the original dialogue between the book’s text and images, and becomes a third surface for interpretive ricochet.

Courtesy Marek Lukáč

“The performance is very minimalist,” Viňarský wrote in an email to Music & Literature, “just as I see László’s text playing with words, sentences and working with the language for its own sake. The same approach I like in working in dance: to work with body language for its own sake, to be attentive and recognize what the body is saying, how the body is able to translate images, thoughts, feeling without too much controlling and navigating. I like to allow the performance to pull at the choreographic structure until over time parts get well worn from overuse. Excess falls away.”

This performance begins with Viňarský and his partner Marek Menšík lying naked on the stage. Flat on their backs, arms overhead, they crane their heads upwards and forwards. Their bodies are not at rest; they are taut, or, as Ottilie Mulzet has it in the book's English translation, they are in a “tautening.” The effort simply to lie on the floor is considerable; one has the feeling this strain is inescapable, perhaps existential–the effort of having dimension at all. Viňarský and Menšík begin to move, to torque and twist under themselves. The music holds a steady, anxious pitch, the sound of a perpetual beginning that refuses to resolve.

One has the sense of an injunction, a choreographic rule or instruction that governs the tension, but it is not so easy to identify what it is. Still, it is utterly believable. In the first chapter of Animalinside, Krasznahorkai describes an entrapped “He”: “He wants to break free, attempts to stretch open the walls, but he has been tautened there by them, and there is nothing else to do but howl, and now and forever he shall be nothing but his own tautening and his own howling . . .” The second sentence introduces a mysterious “They”: “They have placed him inside this moment, but in doing so have excluded him from the moment previous, as well as the one to follow . . .” One at once wonders and does not wonder who “they” might be, just as one wonders why and also implicitly accepts the physical strain. This is a great accomplishment of the performers, a reflection of the rigor and commitment of their physical process.

Courtesy Marek Lukáč

The controlled writhing, the serpent’s struggle, is not without a particular choreography, and the two performers pass through a series of postures that typify an at times beatific abjection. These postures are not drawn directly from the Neumann illustrations, but they are of the same gestural world. In one of the most compelling postures, Menšík sits on crossed feet, his back to the audience, and drops his head so that his torso seems to end without a neck. In its place, he slowly lifts up the palm of his hand. It is a gesture of supplication, but there is also something defiant in it. The flat palm substituting for the human head, which will not hold itself up; the flat palm refusing to give anything away, like the opaque silhouette of Neumann’s dog.

It often comes as a relief, in adaptation between genres, when the original work exists unchanged, when the adapter does not need to point out his own understanding or appreciation of the text by adorning it with his inventions. Such is the case with the text that enters after a sharp blackout, text drawn from Chapter II of Animalinside. The text is delivered clearly and straightforwardly by a disembodied voice in complete darkness. The cuts Viňarský has made to the text, however,—perhaps for the sake of time, though the piece does not suffer from excessive length—make it difficult to trace the surprising move Krasznahorkai makes in the second chapter. The chapter begins with a series of negations: “I have no eyes, no ears, no teeth, no tongue, no brain tissue, no hair, no lungs, no heart, no bowels, no cock, no voice, no smell . . .” And yet, the negations amount, in the end, not to nothingness, but rather to a surprising threat of ubiquity: "but just try to flee, although you can't, because fleeing is no longer possible, because I am here, absolutely close, if I had a smell you would have sensed it already, if I had a form you would have seen it already, but I have no smell, no form, because I can't fit into anything, because within me there is only hatred, only disgust, only fear, only hatred." This turn is harder to recognize in performance.

Courtesy Marek Lukáč

None of the ensuing sections is quite as compelling as the first. When the lights come up again, Viňarský and Menšík are wearing animal-skin pants folded down at the waist like loincloths. Thus clothed, they begin to walk upright, and to interact. The athleticism of Viňarský and Menšík's duet is impressive, and its latent psychological content is compelling: it is alternatively violent and tender, a struggle for power and an expression of care. Viňarský rushes at Menšík and Menšík scoops him up, cradling him like a child. Menšík holds a board-stiff, horizontal Viňarský off the floor with one hand. And yet, though the stage images themselves are compelling, there is something overworked in the choreography. The degree of expertise removes any element of risk, of struggle. That is, the struggle becomes representation: we have entered the realm of acting. The struggle, the body's struggle against itself, so live in the first section, dissipates.

Still, the stage images that Viňarský and Menšík create have a kind of tautness of their own. The second section concludes with Menšík removing Viňarský's and his own pants and kneeling in front of Viňarský with his head dropped sharply down. Instead of a palm lifted in supplication, as in the first section, his hands are held in tight fists at right angles to his torso. It is a complex tableau of incomplete submission and resistance. Or, as Viňarský puts it in the same email to Music & Literature, “Power upon someone expressed without need to touch, to move much, to jump, to fall heavily on the floor and roll around and imitate physical fight.”

Then comes a beautiful interlude, Chapter X of the cahier, in which three twin brothers, "all three of us howl at the stars, we don't know why but it is good to howl, and it was always like this . . ." In the blackout, Viňarský and Menšík move to the center of the stage and when small, twinkly lights in the ceiling come up they wear elongated, simplified dog masks, snouts lifted to the sky. "Starlovers," by the Icelandic band GusGus, plays: "You are in love with God / You are in love with stars / You are in love with something / That will tell you who you are." The two creatures remain still; it is a moment of grace, of the animal arrested, much as the chapter functions in Krasznahorkai's original.

Then comes perhaps the most structurally interesting moment in the piece. First, the lights go down, and when they come up again, Viňarský and Menšík are in the same posture that ended the second section, before the stargazing incident. It is a disconcerting recursion reminiscent of the circling repetitions in Krasznahorkai's text. Had this structural gesture repeated and morphed, it could have been used to great effect. Instead, it is the only of its kind.

Then, an even stranger structural move follows. The performance breaks. Smooth lounge music comes on and Viňarský addresses the audience, announcing that he has snacks to share. He is appealingly direct; the mood at once becomes convivial. Importantly, too, they are nice snacks, and there are more than enough of them: coffee (with optional cream and sugar), chocolate bark, apples, pretzels, kumquats, and more. The quality of the snacks deepens the gesture: it is show, yes, in part, a moment of tonal variety for the sake of composition, but the audience also accepts the food and eats it with pleasure.

The sharing of the snacks halts the performance, immediately dissolving that state of engrossing tension it had cast over the room. Everything Viňarský and Menšík had worked to conjure, they dispensed with. One had the sense of how far one had been taken from oneself. The break offered a return; and yet it too was a performance, and the piece carried on.

There is no similar moment of levity in Krasznahorkai’s original text, and in this departure Viňarský’s adaptation has succeeded. Certainly, thematically, the "civilized moment" that is the sharing of the snacks, the pleasantries, are of Krasznahorkai's world-- these in opposition to the destructive force, the "animalinside." But Viňarský does not evince the same contempt for human civilization as does Krasznahorkai, and these attitudes seem well-matched to their genres. Easier to put up with contempt and hermetic misanthropy in a text than in live performance.

The snacks are also a barter. Viňarský asks the audience to lend him clothing, while Menšík dresses in a tailored suit and tie and slicks his hair back. Menšík then gives a brilliant recitation of one of Krasznahorkai’s final chapters. “My little master, where have you gone? I look for you here, I look for you there, but I can’t find you anywhere; I’m really looking for you, though, because you are my little master, and I can’t find my little food-dish . . . I only say so because it’s dinner-time, otherwise I wouldn’t speak, otherwise I wouldn’t need my little food-dish so much, and otherwise I wouldn’t even need my dinner so much but well, it’s dinner-time and at dinner-time one has to eat dinner, not roam around in the darkness looking for you.” Here, unlike in the disappointing voiceover, Menšík’s tone is spot-on. The ingratiating, the sinister, the humorous, the sincere, the threatening all shade Menšík’s delivery as he approaches the audience. Having just taken pleasure in little treats, the audience cannot but feel implicated in this pathetic economy of consumption, which, as in all of Krasznahorkai’s chapters, eventually turns on itself: “I have to eat dinner, and it has to be like that every day and every week and every month and every year, until the point when I’m all grown up and then your little food-dish won’t be needed any more, because then I will rip away your eyes, because then I will tear off your nose, because then I will burn out your eyes, and I will bite your chin apart . . .”

The piece ends in an antic duet, governed, this time, not by the body’s relation to the ground, but by the head. Vinarksy and Menšík follow their heads in dizzying circles; they bob up and down on their knees. It is as if the head, after this detour into civilized action, has become inordinately weighty, too weighty for the animal body to support. With the two performers on their knees, poised, suspended for the final tableau, a voice comes over the speaker and delivers the final line of Krasznahorkai’s text: “which of the two of us shall be king.”

The line cannot possibly have the same effect in Viňarský’s adaptation as it has in the original. In Krasznahorkai’s text, it comes after the apocalypse in the final chapter, after the complete and remorseless annihilation of the earth. The speaker, somehow, remains; no longer an I, but a we, he asks, or they ask, the only remaining question: “which of the two of us shall be king.”

This question cannot quite be answered within the performance, because what these two dancers have done is more human in scale than Krasznahorkai’s text would ever wish to be. Viňarský and Menšík have not annihilated the earth. They have not, structurally, induced great transformations. Rather, as Viňarský puts it, “We were exploring man’s extreme relationship to his own body, environment, fellow man, and audience. Like a simple prose piece in four parts, each section has its own distinct physical energetic qualities. What can happen if the language of my body is pushed further than its own rules and possibilities suggest?” When it foregrounds the body and its rules, Viňarský’s adaptation succeeds. He has brought to bear on Krasznahorkai’s text and Neumann’s paintings the strengths of his own genre. But the structure—that is, the logic of composition on a larger scale—does not speak to Krasznahorkai’s circling dialectic of negation and presence, malice and comfort, in the same way.

Emily Hoffman is a writer and critic living in New York. Her dance criticism appears in BOMB.