Since his death in 1987 Morton Feldman has developed a cult-like following among musicians. Demand for information about him is remarkable, on- and offline. Feldman wrote numerous essays about his work, but they are often self-conscious in tone, which hampers their persuasiveness. But he was also a formidable talker: his lectures and interviews display a verbal fluency and wit rare among musicians. Reading them can be exhilarating.

As I have spent three years researching the man and his work, I am familiar with the risks of Feldman-intoxication. Those who write about him and his work often knew him personally, and still mourn his premature death. To this day, there has been little in the way of sustained critical consideration of his work among experts. A balanced understanding of the “Feldman phenomenon” remains elusive.

But to me the real elephant in the room is: how do his compositions work? Why are they so successful? How is it that he is able to coax listeners into following his beguiling musical thoughts for hours on end, without breaks?

I don’t have answers to these questions. But it seems to me that a good start is to describe the experience of listening to Feldman’s music, in terms non-musicians can understand. And to admit to the difficulties which recur, even for someone who plays and records the music. After all, the first step towards understanding is often to just observe.

I wrote the following text for the liner notes of my new CD, Ivan Ilić Plays Morton Feldman. Sprinkled throughout are excerpts from the recording, reproduced here with the permission of the record label, Paraty.

***

When I’m listening to this piece I’m drifting and I’m floating, as I do in all your music…. But what I want to know is: are you floating when you’re composing it?

-Bunita Marcus1

Morton Feldman (1926-1987) was a competitive man. In numerous interviews and essays he mentions three composers whose fame and influence he envied: Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, and his close friend, John Cage. “It is a contest,” Feldman said.2

There was a real substantive difference between Feldman and the others: Feldman didn’t use systems to write music. He relied on his instincts. “You know the expression ‘playing by ear’? I compose by ear, and there you have it.”3

Perhaps because of their inscrutable origins in Feldman’s subconscious, his works elude analysis. Feldman provided little guidance: “You cannot analyze why it works,” he said.4 Some writers, instead of analyzing the pieces, describe the listening experience via metaphor. Composer Cornelius Cardew hit on something essential when he said:

Almost all Feldman’s music is slow and soft… I see it as a narrow door, to whose dimensions one has to adapt oneself (as in Alice in Wonderland)… Only when one has become accustomed to the dimness of light can one begin to perceive the richness and variety of colour.”5

The challenge for inexperienced listeners is that they can be so baffled by what they hear in the first few minutes of a piece by Feldman, that they may give up well before their ears adapt. To make matters worse, many listeners are loath to admit that they don’t “get it,” for fear of revealing a lack of musical expertise.

Even though I have listened to many of Feldman’s works multiple times, and I regularly perform his piano music, I still need time to adjust too. I wonder: would it be possible to describe this adjustment, so that listeners know what to expect?

(l-r) Richard Lippold, Morton Feldman, John Cage, & Ray Johnson, 1952

When I listen to the beginning of one of Feldman’s longer pieces, like For Philip Guston (1984) or the String Quartet No. 2 (1983), I follow the notes one by one at first. The same few notes appear over and over again. I start to notice little changes, like the notes arriving at gently unpredictable moments. I begin to focus on the bloom of each note. The insistent, circular motion of the music makes me feel dazed.

About five minutes into the piece, I start to feel edgy. My mind starts to resist. I develop a nagging feeling that the music isn’t going anywhere. I start to become less focused on the music, and more aware of my restlessness. The tension inside me is clearly coming from the music. The repetitions feel provocative, even hostile. No matter how many times I listen to certain pieces by Feldman, this visceral irritability appears early on. I’ve learned that the feeling is a premonition of emotional release. But it’s still disconcerting.

Feldman continues, ever patient, using the same notes, wearing me down. Then, slowly, I start to forget my feelings. I hear the music again, but now it has a glow to it. My ears and mind have adjusted, and my ego fades into the background. It usually takes ten minutes for this transformation to become complete. I can never identify the exact moment when it happens, because, by definition, I forget myself. The part of my personality that wants to measure things has melted away.

Twelve or thirteen minutes into the piece, I am completely acclimated. My mind is calm. My breathing is slower. My ears feel wide open. The details seem more distinct. Listening to the piece is no longer about “the piece” or about “me” but about a spiritual sense with which I am now in tune. I may be in an uncomfortable chair, or thirsty enough to get up for a drink. But I want the spell to continue, and interruption seems unthinkable. “[W]hen my work arrives at one mood, it’s as if I am praying,” Feldman said.6 The music glides along, and my mind glides with it. After fifteen or sixteen minutes, I feel completely secure. Feldman and I now have a pact. His music is so consistent in mood, and in the musical resources he uses, that I instinctively trust that he won’t do anything to “wake me up.” No abrupt accents, no startling dynamic shifts. Any change is introduced delicately. For the rest of the piece, my consciousness only perks up when Feldman changes the notes or the textures of what he’s repeating. My sense of time disappears. The piece can last one hour, or four hours; I know I’ll follow it to the end.

“I think that hypnotism happens when people listen to music, that is to say very rarely,” Feldman once said, with a laugh. “The experience is so foreign to them!”7

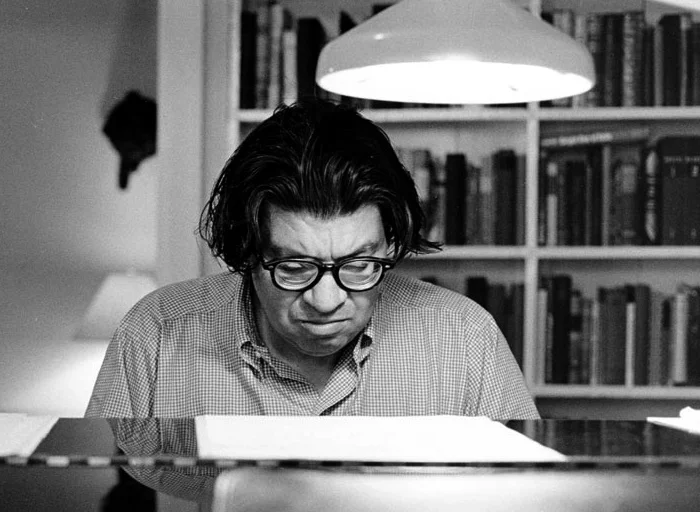

Morton Feldman ca. 1960

As listeners to Feldman’s longer works, we may experience the emotional trajectory I just described: puzzlement—tension—release—trance. But different pieces have different ways of unfolding. Feldman himself would have been wary of these generalizations. In an interview, he said: “Many people feel that if they hear one piece of mine, they[‘ve] heard it all.” If people think it all sounds the same, “it means they are not listening.” But he goes on to say, in the same interview, “I want all my pieces to be the same… By ‘the same’ I mean that [they] travel the same ground all the time.”8

For Bunita Marcus begins with a three-note motive that is twisted and turned over multiple registers, until it seems like the piece will never change textures. The pacing is implacably consistent as well. There are few surprises, and only the changes of register provide variety. The piece feels “tight” during these first eleven minutes [Track 1].9 You can almost feel the composer’s stubborn presence.

What happens next amazes me every time I play the piece: Feldman winds things even tighter. A tiny four-note rhythmic cell teeters, wobbles, and lurches over and over again [Track 2]. The music is reminiscent of “process music,” which follows an inexorable linear path through the possible variations of a motive. But despite the surface resemblance, Feldman’s music is something else: totally unpredictable, repeating itself at times, at other times staggering around rhythmic corners into new, unexpected combinations.

After five minutes of spinning in circles, the piece starts floating into new, freer territory [Track 3]. Whereas the music of Track 1 is stark and foreboding, and Track 2 has a “broken machine” quality, Track 3 marks the beginning of a new texture, with gentle ripples of notes. The phrases become longer, and there’s a hint of sensuality. The variety of notes grows [Track 4] before the opening theme makes a brief reappearance. My favorite excerpt of the piece is the short, loving passage at Track 5 (and the similar passage at Track 9).

At the arrival of Track 6, Feldman proves his inventiveness yet again: with just a hollow chord in the left hand, and two notes in the right hand, he creates a tremendous feeling of space. Few composers can do so much with so little. As pianist John Tilbury wrote, “For where…so many composers were busying themselves filling space, for Feldman the creation of space remained a central preoccupation.”10 Or as Paul Méfano said: “It is as if he lit little sparks in the void.”11

During the last 45 seconds of Track 9 and into Track 10, Feldman takes another tiny fragment and turns its development into a major musical event. Pierre Boulez comes to mind: “Under the influence of Feldman’s music I realized that one could compose music with short cells, even single chords, which come from nothing and disappear into nothing.”12

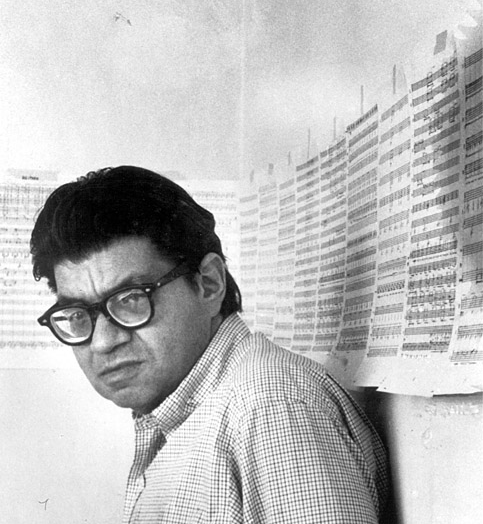

Feldman ca. 1977, with sketches for Neither, his opera with Samuel Beckett

About halfway through the piece [Track 12] Feldman “makes a move”: he has exhausted the previous musical ideas, and he suddenly moves to a new one. Although he saw the convention of splitting pieces into movements as “outmoded,”13 he was realistic enough to know that a long piece can’t sustain itself without change. “You just find ways to survive in this big piece,” he said.14 “When I make a move it might seem a little wrong. You can’t figure out the move… That is also a device for keeping [the piece] going.”15

In this case the new material Feldman introduces is consonance. After thirty-four minutes of dissonant, stark, melancholic sounds, these calm, open intervals, right in the middle of the keyboard, are disarming. Tracks 16 and 17 also include a new element, also consonant: a lovely swaying kind of berceuse, which is so simple in its construction and yet so captivating that it must have made Philip Glass break into a sweat when he first heard it. The figure loses steam in Track 17, and the spaces between the notes start to lengthen.

At Track 17’s three-minute mark, forty-eight minutes into the piece, we hear two slow chords in succession. This short cadential figure signals the beginning of a twenty-minute coda. Although discreet, it’s a critical moment. The notes form a cadence, F dominant 7 to B-flat minor, a typical succession of chords found in 19th or even 18th-century music, but out of context here. This new motive comes to dominate the end of the piece.

From here on, the pace of the piece slows even more. A sense of resignation settles in. At Track 19 the cadence from Track 17 becomes the main fuel which the piece consumes, with a few detours, until just before the end. “In my art I feel myself dying very, very SLOWLY,” Feldman once said.16 The last third of For Bunita Marcus is a wonderful illustration of that idea.

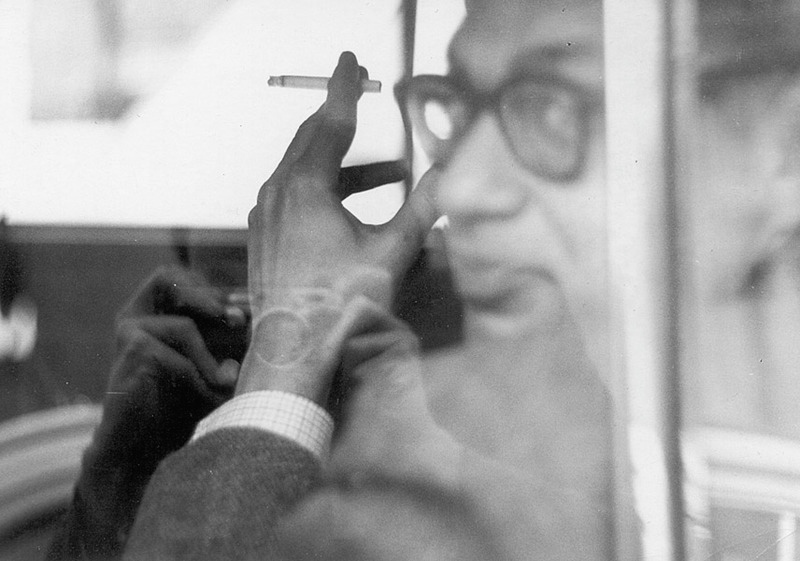

Feldman in Palermo, 1968

Feldman was an expansive communicator about everything except his personal life. But in one of his last lectures, he became uncharacteristically candid. He had just married his student Barbara Monk, and the following week he was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. When he gave the lecture, he knew that his days were numbered.

“I really don’t know how long a piece is going to be.... A lot of times the dictates of a piece ha[ve] to do with purely personal and emotional reasons. The piece that I dedicated to Bunita Marcus, if I could make myself vulnerable, [it] had to do with my mother’s death and the whole idea of someone lingering on. I just didn’t want the piece to die. So compositionally I used this to keep it alive, as a terminal patient, as long as possible.”17

It’s likely that Feldman’s choice of metaphor was influenced by his own looming illness. And today, thirty years after the piece was written, with the knowledge of what he said, I still hear an element of mourning in the piece. And I want it to last just a little bit longer.

Notes

1 Morton Feldman in Middelburg, ed. Raoul Mörchen (Köln: Edition MusikTexte, 2008), 602.

2 From Cole Gagne & Tracy Caras, Soundpieces: Interviews with American Composers, (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1982), 164-177.

3 Interview with Jean-Yves Bosseur from 1967, published in Ecrits et paroles (Paris: L’Harmattan, 1998), 159.

4 Morton Feldman in Middelburg, 94.

5 "The American School of John Cage," a radio program by Cornelius Cardew, broadcast on the Westdeutscher Rundfunk on December 27, 1962.

6 Bálint András Varga, Three Questions for Sixty-Five Composers (University of Rochester Press, 2011), 86.

7 Jean-Yves Bosseur interview, 161.

8 Varga, Three Questions for Sixty-Five Composers, 85.

9 For Bunita Marcus is meant to be listened to from beginning to end. But it’s unreasonable to expect whoever listens to this recording to set aside almost 70 consecutive minutes every time they listen to it. Keeping the piece in one track seems dogmatic, so I divided the recording into multiple tracks. People can now listen to part of it, then pick up where they left off. They can also skip to their favorite sections more easily. Since I divided the piece into separate tracks, I hear the structure differently, especially the subtle shifts of color which are so crucial in Feldman’s music. I’m delighted to have stumbled upon such a simple way of deepening my understanding of the piece. I hope listeners will take advantage of the tracks to explore further than they might have otherwise.

10 John Tilbury, Cornelius Cardew: A Life Unfinished (Matching Tye: Copula, 2008), 143.

11 Varga, Three Questions for Sixty-Five Composers, 175.

12 Ibid., 23.

13 Soundpieces interview.

14 Ibid.

15 Morton Feldman in Middelburg, 130.

16 Jean-Yves Bosseur interview, 158.

17 Morton Feldman in Middelburg, 632.

Ivan Ilić is a Serbian-American pianist. His new CD of For Bunita Marcus is the culmination of 3 years of immersive research into Morton Feldman's life and work. The album is the third and final publication of his "Morton Feldman Trilogy" which includes the album The Transcendentalist (Heresy Records, 2014) and the Art Book/CD/DVD, Detours which Have to Be Investigated (HEAD Geneva, 2014). For more information visit www.ivancdg.com.

Banner image credit: Irene Haupt. 1952 image unattributed. All other images: University of Buffalo collections.