A feature by Madeleine LaRue

A Lesser Day is partly a reconstruction of memory—the narrator is attempting to order her sense of self via five different addresses she’s lived at during a particular period of her life—but it’s also something like a metaphysics of space. Where did this premise, or this structure, come from?

Actually, I had been working on a different book for several years, a novel that’s still unfinished. And in between all of this, I had my son. The hospital I gave birth in had a tiny library, where I happened upon a book by Marie Luise Kaschnitz titled Orte—“Locations” or “Places” in English. I stole it, brought it home, and read it in a state of wonder. It certainly provided one of the impulses for my book, although I didn’t know it at the time. Kaschnitz begins some of the sections of Orte with specific locations, as I do in A Lesser Day, and goes on to search her memory for everything she can remember that’s attached to a particular place in the past—in her case, very far in the past. She was writing about her childhood in the first years of the twentieth century, from a perspective of some seventy years later, near the end of her life.

Madeleine LaRue: One thing that strikes me about all of the stories in The Sleep of the Righteous is Wolfgang Hilbig’s tendency to develop these slowly-unfolding contradictions. He’ll set up one proposition, and then later, seem to state the opposite. This happens even in the very first story: it’s called “The Place of Storms,” but there are, in fact, no storms. And in “The Bottles in the Cellar,” which is my favorite story in the collection—

Isabel Fargo Cole: Mine, too.

ML: It’s so great! And your translation is so beautiful. In that story, there’s a weird contradiction of time. The narrator seems to be terrified of the past that the bottles represent, but also terrified of the future—he’s afraid he’s going to grow up and have to deal with these bottles. And because of these fears, the present is somehow cancelled out. This all seems connected to Hilbig’s relationship to the past, to time in general, and to the post-war state he’s always writing about. Can you comment on that?

IFC: That’s a really interesting observation. I think there are a couple of different levels to it. One of them is that, fundamentally, he always calls into question the idea that you can have a precise idea of reality. Reality can be two things—maybe it’s one thing, maybe it’s the exact opposite, and it’s impossible to figure out what it is. You might try and try to figure it out, and it might look like one thing, but then suddenly turns into the other thing, and then back again . . .

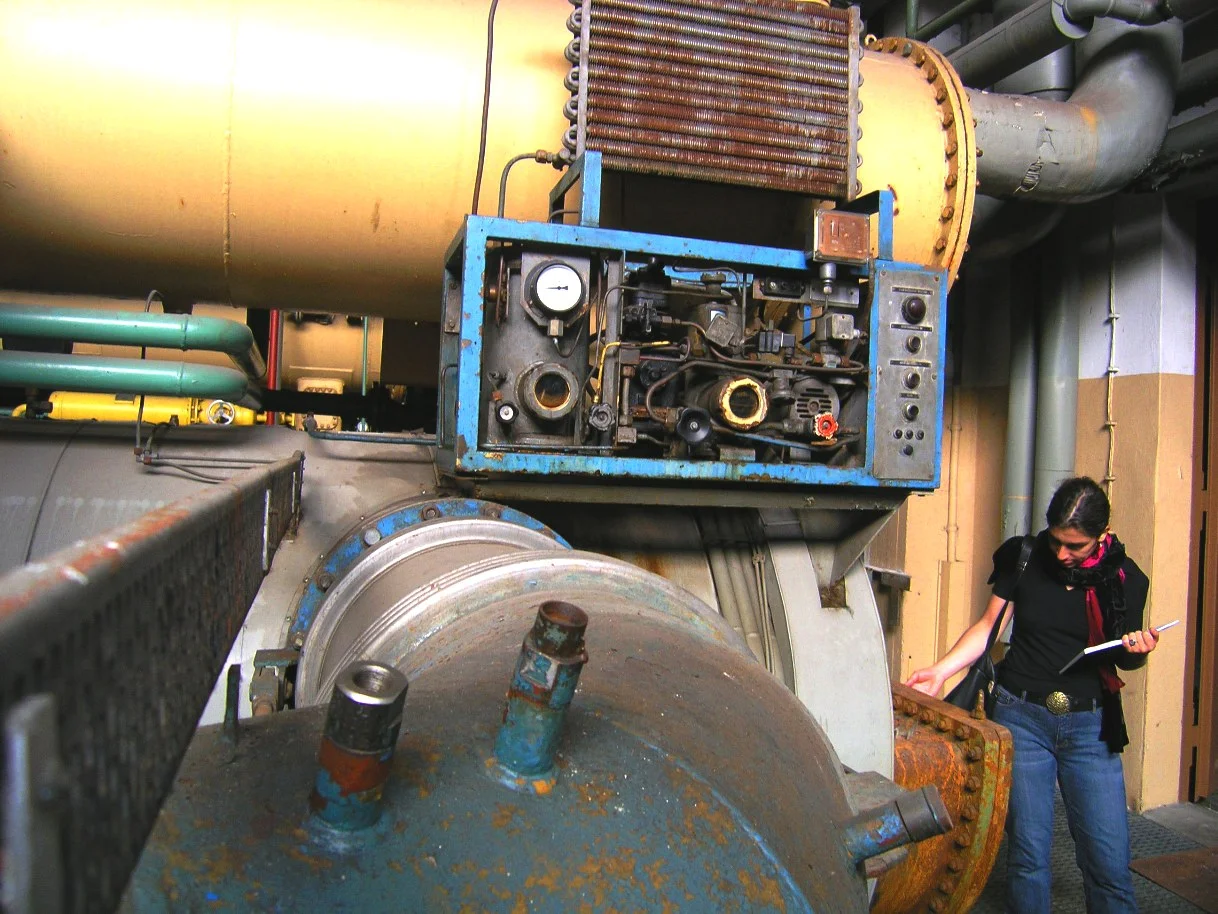

A feature by Katy Derbyshire

The Berlin novelist Inka Parei has written three books—The Shadow-Boxing Woman, What Darkness Was, and The Cold Centre—all of which I have translated for Seagull Books. Recently, we visited two locations: an absolutely unspectacular, slickly modernized residential building in Berlin-Mitte where Inka once lived—in The Shadow-Boxing Woman it is run down and empty, the book’s protagonist and her neighbor the last tenants before the landlord strips and refurbishes the apartments—and then, a short S-Bahn ride away, the 1970s block built for the Socialist Unity Party’s newspaper Neues Deutschland. These two settings have disappeared and the places themselves have become bland parts of today’s Berlin. As in Parei’s stories, it was less the buildings than the history behind them that ignited our conversation, which continued by email . . .