Gate of the Sun

by Elias Khoury

trans. Humphrey Davies

(Archipelago, Jan. 2006)

Reviewed by Keenan McCracken

Deep in Elias Khoury’s Gate of the Sun, the book’s overarching motif crystallizes. “It’s not true that the dying don’t know; if they didn’t, death would lose its meaning and become like a dream,” Khoury writes. “When death loses its meaning, life loses its meaning, and we enter a labyrinth from which there is no exit.” This meditation—one that continues throughout the entire book—is reflective of Khoury’s entire oeuvre. Occasionally, there are writers we encounter who so pointedly articulate the truth of a particular condition or facet of human existence that they nearly colonize it—Proust and memory, Faulkner and the American South, McCarthy and the nature of evil—writers whose identities become so inextricably linked to that thing that formulating a personal understanding of the subject wholly independent of their writing seems impossible. In the case of Elias Khoury, it is the Palestinian history of exile and war in the twentieth century. For “death,” according to Khoury, “liberates the memory,” and it is by drawing on his firsthand experiences of murder and dislocation that he has created a body of work that will very likely be read and remembered decades from now.

Born in 1948 in eastern Beirut to a middle class Orthodox Christian family, Khoury has been in contact with violence for nearly his entire life. A witness to the effects of forced Diaspora on the Palestinians, it was directly after the Six Day War that he decided to join Fatah, a decision that marked the beginning of a long involvement with the PLO that was interrupted only briefly in order for him to attend the prestigious École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris. Returning to Lebanon in the early seventies, Khoury began to publish his first novels, but it wasn’t until over twenty years later that he wrote his magnum opus, a nearly six-hundred-page epic widely considered as one of the preeminent novels of the Palestinian experience.

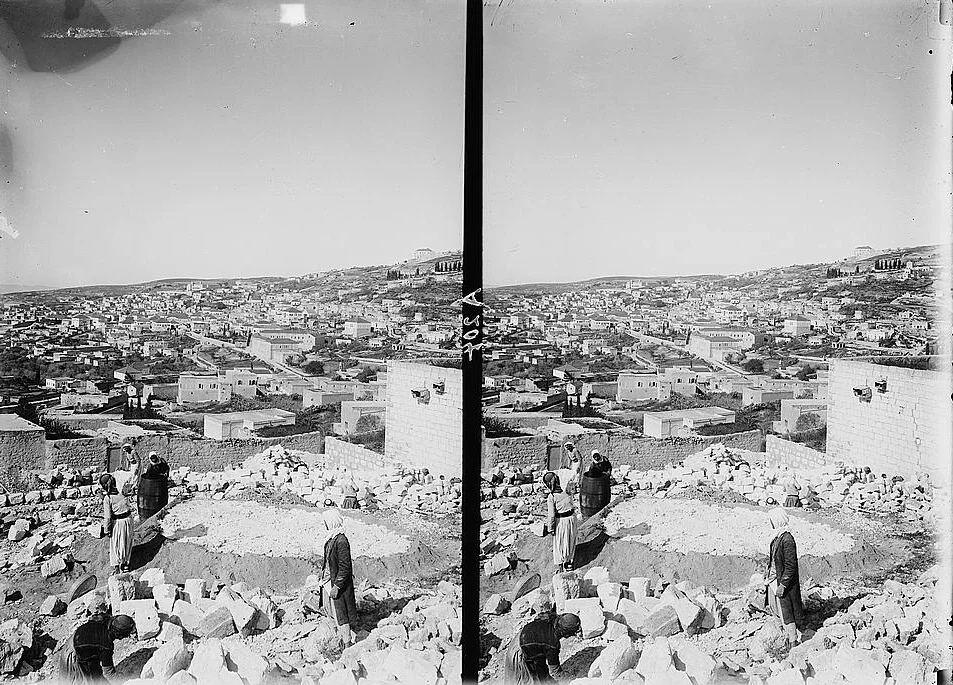

Narrated by a poorly-trained doctor named Khalil working at a makeshift hospital on the grounds of the Shatila refugee camp, Gate of the Sun was inspired by countless private interviews Khoury conducted with Palestinian refugees across the Middle East in order to tell the individual stories of Palestinian exile.

Khalil, recently widowed and one of only two doctors on site, has taken vigil over his friend and spiritual father, Yunes, a famed fedayeen fighter from the early days of the resistance who has been admitted in a coma and has little hope of living. In a Scheherazade-like attempt to forestall death, Khalil engages in a one-sided conversation with Yunes to keep him alive, recounting a flood of anecdotal, often amorphous memories that encircle and occasionally intersect with the narrative heart of the novel—Khalil’s retelling of the love between Yunes and his deceased wife Nahilah. Forced to flee Galilee in 1948 and leave behind Nahilah and his family, Yunes regularly risked his life by sneaking back through the then-permeable border between Lebanon and Israel to visit her, hiding in a cave called Bab al-Shams (the title’s “Gate of the Sun”) where they would secretly meet, spending precious time together until Yunes was forced to return to Lebanon to continue fighting.

It is through Khalil’s formless reminiscences of war, exile, murder, and intimacy that Khoury spins a series of both macabre and ethereal images, tracing the history of Palestinian dislocation from its beginnings in the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. While Khoury himself has described Gate of the Sun as primarily a love story, it is easy to feel that death, not love, acts as the presiding, elemental force of the novel. For Khoury, death—physical, existential, moral—has the ability to permeate and infect the memory of those confronted by it, revealing unwanted, latent recollections from the past. Memory then, once ignited by contact with death, can either become a kind of labyrinthine prison or a tool of erasure used to revise and selectively forget traumatic events. As Khalil tells Yunes, “we forget, but forgetting is a blessing. Without forgetting we would all die of fright and abuse. Memory is the process of organizing what to forget, and what we’re doing now, you and me, is organizing our forgetting.” In Khalil’s case, his life story is mostly worthy of repression: The cold-blooded and mysterious murder of his father by anonymous gunmen, the disappearance of his mother, the acquaintances and close friends who he has seen killed right in front of him; events from his childhood that are unique only in their details, since death, for many Palestinians, has become quotidian.

We soon begin to see that Khalil is not so much bringing this past back to life as he is inearthing it, or rather, engaging in the slow, methodical digging of a kind of metaphysical grave in which to bury Yunes and their shared traumatic history. If the historical leaps and many names and places that Khalil invokes in doing so become disorienting in Gate of the Sun, it is only because memories themselves tend toward asymmetry and an oddly defined interconnectedness, often arising without warning before retreating back toward the subconscious.

In a novel that attempts to convey the breadth of despair of the Palestinians, it is maybe unsurprising that most of the stories recounted by Khalil are ones of bloodshed and grief, but the images are at times so disturbing that they take on an almost surreal quality: sunlight boring into the untended wounds of young men’s corpses left to rot in the imperial heat; small children ruthlessly murdered by Israeli soldiers high on cocaine; a reclusive elderly man dressed in immaculate white clothing that hangs himself from the branch of a lotus tree. The exterior world becomes a torturous source of violence from which the victims of war and exile dissociate in order to protect themselves psychologically: “Even our massacre here in the camp and the flies that hunted me down I see as though they were photos, as though I weren’t remembering but watching. I don’t feel anything but astonishment. Strange, isn’t it? Strange that war should pass like a dream.” What results is an entire people living their lives in state of collective, dreamlike delusion, simultaneously trying to escape from and return to the past.

While Gate of the Sun is a testament to the enormous pain wrought on the Palestinians, Khoury is less interested in demonizing Israel than in conveying the extent of humanity’s failure to prevent violence on the scale of events like the Holocaust and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, and Khoury explicitly draws parallels between the two. According to Khali, nobody is without blame for the genocide inflicted upon European Jews:

You and I and every human being on the face of the planet should have known and not stood by in silence, should have prevented that beast from destroying its victims in that barbaric unprecedented manner. Not because the victims were the Jews but because their death meant the death of humanity within us.

It is by this same logic, according to Khoury, that the dislocation and oppression of Palestinians is not simply the fault of the Israelis, or of all the Arab nations that have turned their backs on them, or even of the U.S.’s facilitation of Israeli aggression, but all of us who willfully ignore the situation and allow it to escalate to the cataclysmic point of devastation.

And yet, Khoury’s work has occasionally been met with disdain even by Palestinians. White Masks, an early novel of Khoury’s written in 1981 during the Lebanese civil war, was originally banned by PLO before being hailed as a masterwork in the pantheon of Arabic literature.

Less poetic and more reportorial, that book—Khoury’s third novel—follows an unnamed journalist’s attempt to solve the unexpected death of a civil servant named Khalil Ahmad Jaber whose brutalized body is found on a mound of garbage. Initially reading as a kind of murder mystery, Khoury’s affinity for shapelessness soon takes over as the narrator recounts his many interviews with those who might have information about the murder, interweaving a strange brocade of disparate stories that involve violence, sex, and political ideology. Unlike Gate of the Sun, however, death is not a Proustian catalyst forcing those affected by it to confront their past, but rather something presently endemic to a society torn apart by civil war. Respectable, unobtrusive people become the victims of horrific acts that signal a total indifference for human life, acts that are just as often perpetrated by members of the PLO as they are by anti-Palestinian forces.

It was Khoury’s depiction, although fictionalized, of the brutality of the very movement he had embraced that led to White Masks be temporarily banned, the most shocking example being a scene in which a teenage militia fighter is taken hostage and indifferently executed. When asked for an explanation by a comrade who had promised the innocent boy that he wouldn’t be murdered, the gunmen replies: “Cut it out, will you? By your logic, no one has anything to do with anything and everyone is innocent . . . He knew what there was to know and was a fighter like the rest of them, and this is a war. We’re not playing games here, and nor are they. They kill us and we kill them.” It’s this abstracted and inhuman relationship to violence that Khoury reveals as a form of self-annihilation on the part of those who decide to blindly kill in the midst of civil war. What its inhabitants are left with is a country pervaded by ruthless insanity, slowly wreaking havoc on itself as the world watches.

Admirably, Khoury’s narratives are much more than intricately constructed amphoras in which to present immutable political views. They are precise and troubling psychological portraits of collective trauma that trace the lasting effects of violence on its victims and question the motives of its perpetrators, whatever nationality or religion they may be. While violence is sometimes a necessary resort for self-preservation, disregard for human life, according to Khoury, can never be justified. Indeed, thoughtless, illogical adherence to savage and anti-humanistic ideals can take hold of even those dedicated to just causes, and it is the defining aspect of Khoury’s fiction that the human element, not the political, always takes precedence. Secondary are the allegiances to countries, to doctrines, or conformity of any kind. For Khoury, those who live their lives enshrouded in death and political instability deserve a voice, and like few before him, he takes up their cause with a fearlessness that we can only marvel at, hoping that maybe in the near future, books like Khoury’s won’t have to be written.

Keenan McCracken is an associate editor at Other Press.