New Finnish Grammar

by Diego Marani

trans. Judith Landry

(Dedalus, Sept. 2011)

Reviewed by Henry Zhang

Halfway through Diego Marani’s New Finnish Grammar, a chaplain offers a thesis—“In Finnish, the word for Bible is Ramatuu, that is, Grammar. Life is a set of rules. Beyond the rule lies sin, incomprehension, perdition”—and a doctor offers an antithesis—“The rule always succeeds the word: this is the great weakness of grammar. The rule is not order, it is just a description of some form of disorder.” Readers acquainted with the devilish trickiness of Finnish, from its fifteen cases to its strange syntax will be relieved to know that Marani, capable linguistic policymaker though he may be, isn’t concerned with giving them an actual grammar lesson.

Grammar, for Diego Marani, is a set of divisions that result from interpreting one’s self and language. Meaning is differential: the raw material of people and language must be defined in opposition to each other, and in time, these differences sediment into things such as nationality and religion. And eventually, like a piece of chalk scrawling without a hand, this differential construction comes to be forgotten; the nation comes to see its identity as something positive and natural, stemming from providence. Yet each division, in the instant of its being drawn, gives hint of its own unnaturalness.

The movement between the natural and unnaturalness of identity, and between confidence in and despair of interpretation, gives New Finnish Grammar its drama. The novel begins with a Dr. Friari, a Finn living in exile in Germany, finding a nameless man washed up with a nasty head wound and retrograde amnesia. His sole possessions are a sailor’s uniform with the words “Sampo Karjalainen” stitched on, and a handkerchief initialed “S.K.” Give credit to the policymaker in charge of promoting multilingualism across Europe for his commitment to frontier languages and countries—Finland is riven between west and east. In the Finnish Civil War, German-backed Finnish White Guards fought against the Soviet-backed Red Guards. The Whites’ goal was to achieve national independence. They won the war, then proceeded to imprison, deport or kill thousands of Reds and their sympathizers.

Friari’s father was one of the deportees, and perished in a labor camp. Such is the doctor’s guilt that it infuses nearly all of his actions: he imagines, for example, that every wounded Finnish sailor sent to his operating table is one of the men that condemned his father. By saving each, he is repaying a karmic debt. So great is Friari’s desire for atonement that after sewing the man’s head shut he makes the first great hermeneutic leap of the book—one which makes us profoundly uncomfortable—he assumes that Sampo, the Finnish equivalent of John Smith (“Half Finland is called Karjalainen!”) is the wounded man. Friari sends Sampo to Helsinki with a note to a neurologist friend to help him.

But the friend never returns from the front, and Sampo remains in a kind of medical limbo, befriending the only person equipped to teach him Finnish, the military chaplain Koskela. Where Friari is haunted by the country’s socialist past and the specter of war, Koskela has inherited its irredentism, its Russophobia, its Shamanistic history and its Lutheran pessimism.

For Koskela, “at heart, we have always been Lutherans, even before we became Christians. The heroes of the Kalevala were already Lutherans in the same way that Achilles and Ulysses were already Orthodox.” It feels question-begging, but to Koskela is a fideist. After the fashion of Kierkegaard, he believes that true knowledge is only accessible through a leap of interpretive faith. “We cannot pronounce the name of God,” he says, “because it would be presumptuous to hope to know Him.”

This leap from the human to the divine is an invocation of a transcendent signified, a kind of hurricane’s eye that justifies and orders the busy whorl of interpretation outside, without which terms like Finnish/Russian or Lutheran/Orthodox are meaningless. The center, however, always comes subsequent to the division, its absence must be downplayed. When Koskela, for example, discourses on the origins of the Sampo, a Finnish Sangraal, he makes the move to tell us it has been destroyed:

“You whose name is Sampo—did you know that you are born of fire? Sampo is a sacred name for the Finns; the whole of the Kalevala revolves around it. No one can say exactly what it was, no one has ever seen it, because it has been destroyed. It might have been the pillar which held up the earth, and whose collapse for ever cut us off from the place we came from.”

Koskela’s effect on Sampo is disastrous. In passages of desperate loneliness, Sampo wanders Helsinki, trying to mimic Finnishness, which Koskela has defined for him as patriotism. At war rallies he throws his voice into the most vocal of chants; he mingles in the crowd of journalists at a hotel, pretending to seek news of war from the front. It gladdens him at first, but soon his doubts overcome him. He cannot, ultimately, feel Finnish. When he tracks down the mother and father of another Sampo Karjalainen, killed in action, the old couple mistake him for their son, giving him a panic attack and making us feel, with him, the uncanny effects of a denatured identity: behind his masked name is a hideous mannequin’s face, emptied of meaning. Sampo’s feeling that “there would always be something left over, some unspendable small change” of meaning, is a melancholic yearning for the jouissance of a transcendental origin, which Koskela has mislead him into thinking exists.

Sampo’s disease, his feeling that all divisions are somehow unnatural, may be termed agnosia. He has caught a glimpse of a Finland denatured of Finnishness, stripped of the grammar of national identity, in which the concept of nation and not-nation shift in and out of focus. Observe that his first great moment of unhappiness after his accident is when he is obliged to look at a map:

“I looked first at his eyes and then at the map, frowning in a state of growing confusion. Then at last I understood. Of course, the doctor wanted me to show him where I came from . . . It was then that I felt my blood run cold. It was like leaning over the brim of an abyss. I recognized the shapes carved out on the map by the red scars of the frontiers, but I no longer knew what they were. The capital letters straddling valleys and mountains meant nothing to me. France, Germany, Austria, Hungary, Romania wandered around my mind as outlined shapes, but I could no longer put a name to them.”

Finland, in the novel’s present (1943), is a country where “you could see the process…still visible that brought each single European state into the same condition, that built all our patriotisms—the ones we are now trying to get rid of” (emphasis mine). By suggesting that national myths are something that “we are now trying to get rid of,” Marani opens up the question of an alternative to Koskela’s commitment to this grammar of differences. Is there a world in which Sampo’s agnosia would not result in such melancholy? Is it possible to live in a denatured world, in which all divisions are suspect?

The book offers no easy answer, but perhaps Marani himself does: one of his goals, when he invented his own language in the nineties, was “to show that...you can play with [languages], that they have always been mixing one another, that purity in language is as false as in race.” Yet none of the characters is privy to this lightheartedness. Sampo’s name comes to betray him in the final chapters of the book, and Friari, though he represents a kind of disenchantment with Koskela’s hermeneutic authoritarianism, still cannot do without a national grammar either, despite his ironic disavowals of it:

“all these years I have been trying relentlessly to right a wrong which was not my own . . . the whole of Finland had to absolve me, every single Finn had to pass through my hands in order that the pardon be complete . . . This unforgiving fatherland killed my own father; it drove me into exile, offered me nothing but affliction, and I yearn for it and curse it to this day.”

Marani shares in Friari’s ambivalence—he is at once someone who writes novels about the futility of linguistic institutions and someone who has built a highly successful career as a translator in the EU. Marani works as a policy officer at the European Commission's Directorate-General for Interpretation, ensuring member-states and their delegates the freedom to speak their own languages. In the nineties he was translating for Council of the European Union, one of the EU’s legislative bodies, and it was here that he invented a language called Europanto. Half-hoax, half-performance piece, Europanto is the child of conflict: critics of the EU’s language policies say that Western European languages—German, Italian, French, dominate the stage, leaving little room for “small state, regional or minority languages,” meaning mostly Slavic languages.

Against the stifling edicts of lingua francas, which are consistently harder to learn for Slavs, Europanto has no fixed set of rules—merely suggestions. Say I’m Spanish and you’re French. Europanto’s “rule” states that I can say pretty much any combination of Spanish and French—the syntax and vocabulary are negotiable—as long as I am making an effort in good faith to draw on knowledge I think you’ll understand. Such a rule is essentially a blank-check allowance for improvisation, collectivity, agonism—is, in fact, unruliness itself. Too, it is a kind of expression of desire to avoid monoculture. On Wikipedia, Marani (or another editor who seems to be channeling his ethos) commented that his intention with Europanto was to make the point that “a common language is not the solution. A sharing of languages would be one...Europe is made of borders. If on each border people would learn each other’s language we would have a true multilingual and better integrated Europe.”

With this statement, Marani seems hopeful in a way none of his characters dares to be. One wants to ask him: In a EU where Slavic immigrants are kept out, not only from the halls of council meetings, but from civic and social and public spaces, isn’t it still true that the this immigrant will have to work much harder for his Europanto to be understood? Isn’t the move to condemn linguistic protectionism opening language up to a kind of neoliberal rhetoric? Nor, seemingly, is Marani exempt from this kind of exclusionism: look at his novel, written in Europanto, called Las Adventures des Inspector Cabillot, and you will note its title is a blend of overwhelmingly Western European languages. You may want to get rid of the gate-keeping prescriptions of grammar, one wants to ask, but aren’t you forgetting that on your side of the gate there are so many more people, free now to trample all over my language and culture?

Marani’s answer: the language that “wins” is irremediably contaminated by the losing languages: “Keeping this in mind, we can have a more relaxed and open approach to language learning and be less afraid of the threat of English dominance. Speaking English we take possession of it, we make it a language of our own, we pollute it with our way of thinking, our vision of reality, our national character.” It’s an answer that doesn’t totally satisfy—like an inspired version of something I might tell my parents, in middle school, to get out of having to attend Chinese class.

Yet why should his answer satisfy? All novels are the workings-out of problems, and rarely, despite their denouements, give closure. Marani dedicates Last of the Vostyachs to exploring what it’s like to be the speaker of a nearly dead language. The protagonist, his clan wiped out by the Russians, is the last remaining speaker of Vostyach, but in dying, Vostyach has contaminated Finnish and Russian both, so that the one villainous character, career founded on the suppression of this fact, seems not only hopeless, but dangerous to us. Vostyach’s absorption into the other languages is hardly any consolation to the Vostyach himself, but refusing to recognize it is what produces more conflict. The pursuit of this recognition of linguistic mutation is the central tension in all of Marani’s other novels. The final book in the New Finnish Grammar trilogy, The Interpreter, is about a UN interpreter who thinks he has stumbled on the proto language behind all human speech, and all the people who are convinced he’s mad. Even when Marani changes tack to religion, as in God’s Dog, the villains are always exegetes, their ideology always that of a linguistic purity under attack.

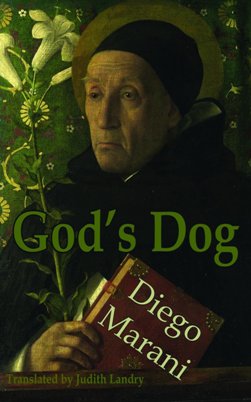

God's Dog

by Diego Marani

trans. Judith Landry

(Dedalus, Dec. 2014)

If agnosia is what drives Sampo Karjalainen to despair in New Finnish Grammar, it is what drives Dominic Salazar, the protagonist of God’s Dog, back into his cage.

“were I to be set free, I wouldn’t even dare to leave my cage. where would I fly to, in this empty, senseless world? I need a mission. When all's said and done, it isn’t a question of faith. Sometimes I actually whether I have any faith at all.”

As a child, Salazar was found in the ruin of the 2010 Haitian earthquake and taken in by the agents of the Vatican. By the time he reaches adulthood, graduating from the papal police academy, the Roman Catholic church has codified Pope Benedict XVI’s conservative dogmas and taken control of the Italian parliament. “Number 2354 of the Catholic Catechism,” for example, has been redrafted from an anti-pornography credo to this:

“The citizen is conscience-bound to ignore the orders of the civil authorities when these run counter to the demands of the moral order, to fundamental rights or the teachings of the gospel. It was this that led many Catholics to rebel against the godless laws of the Italian Republic.”

In this Orwellian vision of a neo-Rome, atheism is taxed, heresy is a thought crime, and the Church has acquired a monopoly on the right to die, relocating patients with terminal diseases to hospices which draw out, rather than reduce, their suffering. Agents like Salazar masquerade as normal clergymen, offering counsel to the ill, whose fear of incriminating themselves results in a panoptic society: but unlike in Orwell, and perhaps showing us some of Marani’s old-fashionedness, the technology of control is all analog: confessionals that function as reconnaissance points for agents and their handlers, rosaries that are forced onto sufferers from books, and an abundance of missals and other paper. Against the papacy, a confederacy of euthanasiasts are helping sufferers to die prematurely, and so the mission that Salazar’s handler-confessor gives him is to hunt them down.

God’s Dog is human where New Finnish Grammar is metaphysical and in it, Marani’s sights have been set on something much more personal to him: Italian sacerdotalism and immanentism, a bureaucracy of priests and icons. The Emilia-Romagna region, from which he hails, has a strong history of anti-clericalism, and Marani, at his funniest in the novel, writes a passage in which a foppish Vatican bureaucrat bores Salazar with a speech about ranks of angels, which he believes are also bureaucrats.

“The angelic orders could not miss out on such an occasion, so here they’ll all be, from the Powers to the Dominions and the Principalities. The archangels will be here too, probably the odd Seraph. I don’t know about the Thrones, they’re rather busy, particularly at Easter. I’m not sure about the Cherubim, either, that would be too dangerous.”

Salazar is unlikeable, coming off as alternately juvenile and menacing. His delight in writing poorly thought-out heresies in his journal and hiding a shisha pipe in a holy water sprinkler remind one of a child up to some minor devilry while his parents are gone. But his heresy—to solve Europe’s immigration problem by blending Islam with Christianity—seems much less arbitrary when we discover its motivating force. Salazar, away from Rome and living in Amsterdam, has fallen in love with a Dutch Muslim, Gunter. Gunter, we sense, is on the brink of converting him to a different kind of life, but as soon as Salazar returns to Rome, he finds himself pulled into the orbit of Papal authority. Despite his great competence as a detective, Salazar’s weakness is that he cannot give himself to a cause, only to people. Survival, for him, is not mere physical safety (he has no problem risking his life on the job) but submersion in a vision strong enough to prevent him from thinking for himself: “like a safety valve which kicks in whenever I start to delve into my memories.”

Nonetheless, a part of Gunter’s vision has contaminated him permanently, spilling the boundaries of their different religions. Gunter, a scientist, wants to prove that monkeys have neurons that allow them to speak language, which would mean that they would share a “soul” with humans and confirming, rather than refuting, his faith in a God. This may be bad sci-fi, and worse theology, but clues us in to Marani’s appreciation for this spilling over of boundaries, of ideological and linguistic contamination, which he indicated in an interview at the Auckland Writers & Readers Festival:

“An example: in Egypt they speak Arabic, but the Egyptian Arabic is different from the Algerian and Libyan and other Arabics. It is different because it contains a language that doesn’t exist anymore, which is Coptic. So Coptic is a dead language, but dying it has contaminated, it has influenced the Arabic of Egypt. So languages simply are absorbed by another one, but they never really die.”

Contamination, for, Marani represents the trace of fellowship among two peoples that disproves their attempts to define themselves against the other. It is not faith that Marani damns, but sectarian conflict, the religious equivalent of grammatical nitpicking: “If you protect the language in an artificial way with the interdictions, with rules and barriers, well it is like putting it in a cage in the zoo and this is not the way because when the beast is dead the cage is empty.” Marani’s thoughts very nearly match those of Friari’s: “Human stupidity has divided language up into a plurality of grammars, each claiming to be the ‘right’ one, to reflect the clarity of thought of a whole people . . . deluding itself that it is these same rules that will resolve life’s mysteries.”

The most misguided of Marani’s characters deny the existence of this contamination. Both Koskela and one of the characters in The Last of the Vostyachs are engaged in trying to validate a long-discredited linguistic theory which states that Finnish developed from a language family that is separate the one which predates Russian, Mongolian and Japanese. It has been largely replaced by a proposed language family called Eskimo-Aleutian, which gave its traits to—among others—Finnish and Russian.

The point, for Marani is not to return to a prior unity, to a global language that is spoken exactly: difference is unavoidable. The point is to understand that each difference is less than it seems, that it can be transgressed, that slippage and contamination happen, and that each grammar—national, religious, cultural—has exceptions to its rule.

Henry Zhang lives in Beijing, China, where he writes about and translates fiction about people who aren't getting any younger.