SILENCE CHARGED AND CHANGING

Black Case Volume I &II: Return from Exile

by Joseph Jarman, with a new preface by Thulani Davis and an introduction by Brent Hayes Edwards

(Blank Forms Editions, 2019)

When composer, priest, poet, and instrumentalist Joseph Jarman passed away in January 2019, a bell sounded in the hearts of thousands of listeners. As an early member of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM), as well as its flagship group, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Jarman was a key figure in the articulation of Great Black Music as a multi-generational ethic rather than a standard repertoire. As an ordained Buddhist priest, Jarman’s solicitude transcended philosophical affinity and deepened throughout his life as his music evolved. His musical, poetic, and religious paths appear to have been mutually informative, in spite of a hiatus from public performance in the nineties—and to encounter Jarman’s own words is to understand as much. The full breadth of this complexity is celebrated in the long-awaited reissue of Black Case Volume I & II: Return from Exile, a blend of smut and sutra, poetry and polemic, that feels like a reaffirmation of Jarman’s ambitious vision in the present day.

Black Case wears its context proudly. A near-facsimile of the original 1977 publication by the Art Ensemble of Chicago (which itself was built upon a coil-bound printing from 1974), the volume serves as a time capsule of a key period in the development of an emancipatory musical and cultural program, and an intimate portrait of the artist-as-revolutionary. Black Case, then, feels most contemporary where it is most of its time, as a document of Black militancy and programmatic self-determination in which—to paraphrase Larry Neal’s 1968 summary of the Black Arts Movement—ethics and aesthetics, individual and community, are tightly unified.

Jarman’s writing and his actions exemplify this clarity of purpose. Likewise, the volume’s subtitle, Return from Exile, reflects a movement from individualism to collective concern. As Jarman explains in an introduction to the second edition, “Exile is a state of mind that people get into in order to escape from the reality of themselves in the world of the now. It is a safe place inside the mind full of mostly lies and false visions that allow the being to think that it is free of the responsibility of living in a world with all other living things.” In this holistic description, the essence of the individual, “the reality of themselves,” is both historical and distributed as a series of relationships. Jarman abandons a standpoint of immediacy—“the world of the now”—for a sense of the continuity and deep interrelatedness of all beings. In describing the direction of this insight as a “return,” he affirms the priority of social and spiritual life over individual concern.

This theme of exile echoes throughout the work presented in Black Case, where it entails alienation from civic participation; from the life of music; from full speech and the power of language as sound. These thematic returns are stated in multiple registers, once again binding conscience and community, art and life. Whether setting forth an original zen hymnal or narrating a series of intensely personal trials, Jarman is clear about the political determinations of spiritual health. Jarman expands on his prefatory remark in the program notes for a 1975 duo performance with Leonard Jones at the University of Chicago:

In 1947, ten years after I was born, I became extremely aware of being Black in America—that was the beginning of my political involvement in the struggle for the liberation of my people and later the realization that we must work to bring freedom, justice, equality, and happiness to everyone.

“Joseph Jarman,” credit rocor and shared under CC BY-NC 2.0

Jarman describes an exile of consciousness and factual circumstance, coming of age at the junction of domestic racism and imperial war. As Brent Hayes Edwards explains in his introduction, Jarman entered the Armed Forces in 1955, only to be injured during a traumatic siege in Vietnam, and reassigned to an infantry band for the remainder of his service. The violent incident and often hellish scenery of Black Case—midcourse of which one witnesses “the unforgiven/eating babies”—is scarcely intelligible without reference to this wartime confirmation of adolescent misgivings, and the demons we meet here are nothing but historical. Back in Chicago, Jarman entered a period of personal turmoil that escalated into a year-long inability to speak. He wandered in pursuit of health and inspiration, finding a measure of both in a musical encounter in El Paso, which he recounts in verse: “i/remember the alto player, clean like Lou/Donaldson and Bird, singing magic through/the metal tube.”

The lost years culminating in this epiphany furnish one of Jarman’s best-known poems a scenery of elated distress. Its speaker disembarks a Greyhound bus “high off - pills, smack/other deadly joys, mute, silent and noiseless.” In these lines, narcotic confusion is a spiritual predicament, and the doubling of muteness (“silent and noiseless”) alludes not only to a lack of inspiration, but a missing instrument. This is the kind of technical distinction that any musician would understand, collapsing the potentiality of silence into the impotency of soundlessness. Throughout, the latent poet’s muteness operates in two directions: as a scalded retreat from reality as well as an act of self-assertion. Accosted by racist police, he writes on his pad “MUTE” “I CANNOT SPEAK.” Here Jarman’s negative capacity assumes the character of positive protest in confrontation with repressive environs.

The poems found in Black Case appear mostly undated and untitled, belonging to an the eternal present of a given reader’s encounter with their music, but this self-mythologizing poem is placed and approximately dated at the outset, “spring 1959,” marking the turning point in a creative project forged of lived experience.

*

This anecdote—of sound bursting from oppression and placing the poet in possession of a formerly involuntary silence—is credited by Jarman as the first poem that he ever wrote. That said, while Black Case narrates a personal journey into the communal essence of a music—the eponymous return from exile—it is assembled post hoc, and its chronology has more in common with a religious service than a linear narrative of artistic formation. Fittingly, then, Jarman’s introductory grace is followed by a typographical chant, descending the page in repetition:

we pray o God

for the ego

death

and that the power

of the evil vibration

be taken

from our presence

This columnar mantra faces a blank page, as a moment of visual silence and a representation of the nothingness supporting the forthcoming torrent of language. From this slate proceeds an unpunctuated spool of recollection, depicting the artist’s political and sensory milieu growing up on the South Side of Chicago. The poem commences from the earliest structures of childhood experience, before any awareness of exile, with a religious invocation of light:

to start then the first day coming into the light

being taught to live the land like any city boy

at dawn feeling the strong door of gas from

the car we’d ride in daily …

Immediately, this anecdotal bildung is rerouted through a field of conflictual experience; sexual exploits and adrenalized delinquency are condensed into a momentous run-on sentence. Bookended by childhood games of war (“cowboys&indians always i’d want to be the good guy”) and scenes of ideological conscription (“it is/only right to join the army and die for god”), the poem hurtles toward a moment of personal punctuation:

… and we laughed taking what we wanted as any

man does to the death the disease the horror the

middle class lie that america was then then to fall

as if asleep waking seeing hearing feeling where it was

is will be forever the SOUND of gods allGODS

the self-MUSIC finally word to end part page one

the happening say my life say it.

This dense conclusion is worth reciting for its multiple resonances. In these lines, the fall of America—a revolutionist’s conviction and a conservative commonplace alike, depending on the proposed trajectory of descent—figures ambivalently alongside the artist’s own awakening. In this polyvalent crescendo, America falls as if to sleep, collapsing into self-satisfied complacency rather than descending in flames. And yet, from the same implicated breath, one reads that the poet himself is the one who falls—away from the manic values of a ruinous society, and to sleep insofar as to awake suggests a prior dormancy. One should consider these equally supportable readings as harmonic layers of meaning rather than grammatical ambiguities, affirming both interpretive paths in a breath. As the present tense supplants its past (“where it was is will be”), the macabre actuality of American society is to be superseded by the creativity of its excluded part. This autobiographical prelude terminates with the advent of music, a unity of individual expression and universal truth, for Jarman names “self-MUSIC” as the sound of “allGODS.”

In this poem and throughout Black Case, music summarizes the social plane from which it emanates, just as philosophical concepts include the history from which they borrow form. This summary of juvenile experience evinces nothing like the lapsarian nostalgia for childhood that typifies so much romantic poetry; rather, it describes the ideological shadow plane that Jarman has termed “exile,” a space of escapist malaise. This program culminates in the full speech of its denouement—the musicalized injunction to “say it”—and the spiritual necessity of this concession to chronology is clear from Jarman’s reflexive gesture toward the book itself, where music materializes a “word to end part page one.” Foregrounding the ordinality of his career-spanning anthology, Jarman offers a progressive outlook in the true sense, of a self-surmounting process that improves the world by way of its participants.

Only abreast of this pre-history do we arrive with Jarman in El Paso, where the crucible of speechlessness opens epiphanically onto “the rush of jazz.” In this somewhat Dantean account, Jarman’s silence coincides with a period of purgation, as the poet dwells amid the “neon pleasure of America’ biggest border/town” pending spiritual ascent. This passage has less in common with the moral topographies of Christianity, however, than with the pendulum of worldly attachment preceding enlightenment in the life of the Buddha. Between discipline and prodigality, Jarman finds in music a social vehicle for the cause of selflessness, thus breaking the silence and accepting the task of collaboration with surroundings.

*

Muteness is not assent to silence but to the sound of otherness. In Jarman’s discovery, it is the void base of expressive speech, irreducible to language: “with it to sing/a stronger song/of yourself.” Jarman posits a close identity of sound and silence, noise and signal, subject and object, throughout this spiritual and political treatise:

music

anywhere silent noise love sound

vibration

free of air, clear somehow

even of America …

One would be mistaken, however, to depict Jarman’s more plethoric silence as a post-Cagean program of acquiescence to sonic happenstance. As seen, the individual voice is a willful specialization of history, and the social determination of Jarman’s music, not to mention the scalded quiet it presumes by way of support, sets Jarman’s quest polemically apart from tendencies of European descent, in spite of his self-professed affinity for the philosophy and music of John Cage and his collaborators.

Jarman’s post-exilic silence, “clear somehow/even of America,” traverses disavowal in order to affirm a higher and more basic society, that of Great Black Music; whereas America is the preponderant quantity of which Cage’s silence is never truly exempt, filtering the din of actuality and accidentally affirming an artistic identity with the status quo. In a racist society, one might venture to make a meaningful distinction between the silence of the oppressor and the silence of the oppressed, where one corresponds to acceptance and the other to refusal. Thus, as Cage and other uneasy inheritors of European tradition sought democracy in indeterminacy, Black radicals of Jarman’s generation formalized a program of cultural determination.

The intentional silences of Jarman’s work are suffused with idiom, as a negative figure of what poet Amiri Baraka calls “the Changing Same.” By this, Baraka observes a dialectical identity of the “blues impulse” driving the many facets that he gathers under the sign of New Black Music. Written the year after a small group of Black musicians convened the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians in Chicago, Baraka’s influential essay describes something akin to Jarman’s platform in Black Case, of self-Music in community with allGODS. The blues impulse offers “an expression of the culture at its most un-self (therefore showing the larger consciousness of a one self, immune to bullshit) conscious.”

The negative moment of creativity is audible in the near-rhyme and conceptual equivalence of the “un-self” and “one self,” where unity is the product of separation from coercive bullshit. Here Baraka describes the exile of the Black artist at market and perhaps more broadly, in terms that will influence Jarman’s own. One might offer that in Jarman’s introduction to Black Case, exile is an escape from the consciousness of one self, into the immediacy of oneself. This is a slight but significant change in standpoint, for in Baraka’s writing, a simple space (or glyphic interval of silence, facilitating difference) disturbs the pronominal integrity of any ‘oneself,’ offering a figure of collectivity in its place. To get there, however, the isolated consciousness must negate its subjugation in the guise of self-concern. “Hence the so-called avant-garde or new music, the new Black Music, is separate because it seeks to be equally separate, equally unself-conscious … meaning more conscious of the real weights of existence,” Baraka writes.

This language, of equality in separation, bears some resemblance to Cage’s own programmatic insistence on horizontal equality in musical situations. In scholar Rebecca Y. Kim’s evaluation of Cage’s vexed relationship to jazz, “separate togetherness” describes the ideal conditions for performance under the sign of indeterminacy. While this vaunted premise is said to borrow license from jazz improvisation, Kim explains, the composer nonetheless takes exception to the genre as though it were a game of conversational one-upmanship, citing a supposed seriality of solos and a sameness of form.

Pertinently, Cage made these dismissive remarks only weeks after a collaboration with Jarman and his quartet in November of 1965, at the invitation of the AACM. As Kim explains in her retelling of the event, Jarman’s enthusiasm outbounds Cage’s engagement. In a press release for the concert, Jarman writes of his “great artistic and conceptual indebtedness” to Cage, who ironically expresses his own gratitude for this jazz lesson in strictly aversive terms. To restate the importance of this missed encounter, one might suggest that Cagean indeterminacy, which prizes the discrete agency of absolutely unobliged participants, recommences after 1965 from the negation—or the knowing ignorance—of a specifically Black aesthetic.

Cage and Baraka both appear to recommend programs of cultural negativity that bear initially upon self-consciousness, but Cage’s aesthetic neglects the positive moment of apprehension by which the negation attains to self-identity, underwritten as it is by a democratic formalism that places equality of positions before equality of persons. Cage’s distinctly American Zen impels the assertion that “everything is music,” but this music-without-a-subject precludes the “digging of everything” that Baraka counsels as an affirmative standpoint. This digging of everything, unto a “really new, really all inclusive music,” entails sensitivity to the socially contingent vehicle of sound. Musical idiom attests to “different placements of spirit,” Baraka writes, and music’s universality ultimately requires the mediation of a people, such that the differences comprising its genres are “even ‘purely’ social.”

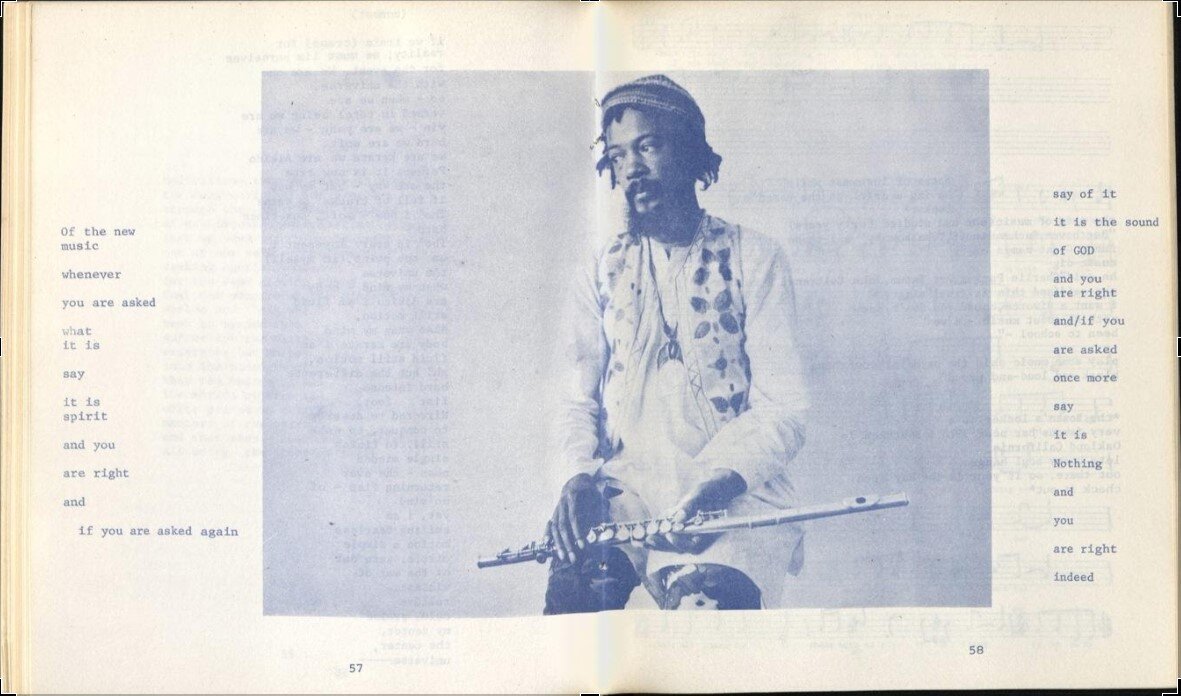

Jarman attests to this changing essence of music in a sparsely lineated koan, spanning two consecutive pages and framing a photograph of the author:

Of the new

music

whenever

you are asked

what

it is

sayit is

spirit

and you

are right

and

if you are asked again

say of it

it is the sound

of GOD

and you

are right

and/if you

are asked

once more

say

it is

Nothing

and

you

are right

indeed

A scan from the original 1977 version of Black Case

Jarman’s apophatic approach to the new music appears equal parts indebted to Cagean post-musicology, authorized by nothingness, and Barakan historical materialism, with its unique conception of Black Spirit—even positing music as an ulterior force by which the two concepts are brought into agreement. The first two moments of this tripartite identity are addressed all but explicitly by Baraka himself in “The Changing Same”:

The meeting of the practical God (i.e., of the existent American idiom) and the mystical (abstract) God is also the meeting of the tones, of the moods, of the knowledge, the different musics and the emergence of the new music, the really new music, the all-inclusive whole.

But it is the third term, Nothing, from which one adduces Jarman’s deep involvement in Buddhist philosophy, and his familiarity with Cage’s thought.

As the ample spacing of the text convokes visual silence, Jarman’s decision to center his own portrait requests attribution. Thus, with a spiritual precision incumbent upon priesthood, Jarman synthesizes these approaches under the paradoxical sign of attributed nothingness. Much as his description of muteness demands that the reader conceive of silence, rather than speech, as an agent of meaning, this signatory centerfold is placed as a meditation—the assumption of a universal self by way of place and person.

*

Throughout Black Case, Jarman furnishes a post-Cagean transparency of standpoint—“to control/only nothing … our object/to be/air”—with a culturally affirmative program of self-realization through music. And while the 1965 collaboration apparently evades the Cagean ideal of audible quantities “coexisting independently in space,” the relative motility of the musicians inspired Jarman to further develop a live presentation in which audience and performers alike factor as sets of coordinates rather than static entities.

In many ways, Jarman’s development of this idea—a 1971 duo recording with Anthony Braxton is called Together Alone—offers a vision of musical mutualism more compelling than the coldly inclusive civics one might extrapolate from Cage’s aversions. This holistic socio-musicology—wherein voice is tributary of sound, and the soloist emerges only as the negative self-determination of the group—underscores the major insight of his poetry:

-it is time

yes;to move from

yourself to

yourself again

to know

what you are

song

Song For

Joseph Jarman (alto sax, recitation), William Brimfield (trumpet), Fred Anderson (tenor sax), Christopher Gaddy (piano), Charles Clark (bass), Steve McCall (drums), and Thurman Barker (drums)

Delmark Records (1967)

In Jarman’s social ontology, the individual is song, which places them in concert with a variety of hostile, crowding, and congenial factors. This predicament motivates Jarman’s best known poem, “Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City,” a monologue of existential agitation composed after the fashion of Baraka’s 1960s, and a searing text of exile as a civil and spiritual predicament. Having appeared in recitation on Jarman’s 1967 debut album, Song For, the poem shows up relatively late in Jarman’s 1977 sequence, its pessimism and grit contrasting the preceding rituals of purpose and devotion. Jarman makes many such decisions, balancing sexually explicit vignettes with exhortation toward a multiform God, and scenes of racist discrimination and violence with vistas of spiritual serenity. As a poem, “Non-Cognitive Aspects…” includes many abrupt turns itself, where Jarman writes the following passage of narcotic escapism and religious immanence three times consecutively, eventually removing all the spaces between words as though enacting restriction:

Could have spirits among stones

uppity the force of becoming

what art was made to return

the vainness of our pipes, smoking

near fountains, the church pronouncing

the hell/ of where we are

In an essay named after Jarman’s composition, poet and critic Sean Bonney speaks of the identity of poetry with jazz forged during the militant 1960s, and the political uses of sound in this milieu. Throughout this period, says Bonney, poems were “incorporated into the sonic field in such a way that they became one equal element in the collective of voices that made up the piece.” Again one glimpses the ideal of separate integrality, this time spanning two orders of meaning, which Bonney more or less describes as an attempt to semanticize jazz style:

The musical note and the word are two extremes of communication: when brought together, the word explodes the note and brings out what was hidden inside it, resulting in an explosive tension which is itself the communicatory material. Meanwhile, the music shatters the voice. The word, in music, is precisely what is not necessary, what does not belong, but as such it is that which can slice through harmonic hierarchy, and reduce it to dust.

Jarman’s music and writing exemplify this mutual sublimation, which makes the presence of these poems on the page a kind of score. Notably, many of the poems in Jarman’s written oeuvre were rendered instrumentally by members of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, omitting language in a kind of free translation. As Brent Hayes Edwards observes, Jarman repudiates the distinction between music and language altogether, attributing their seeming incommensurability to one-sidedness on the part of the listener. “Why, please tell me/must i limit myself/to a saxophone or clarinet,” Jarman writes, “when all sound all movement/springs from the same breath.”

Bonney’s description of jazz poetry, by comparison, somewhat reifies the division it would overcome. Jarman’s practical conception of the sound as semantically imbued already realizes this unity, in which, as Bonney writes, “the pressure brought to bear on music by language, and vice versa, can provoke the realization of an art that reaches beyond itself … thus becoming a real, and direct, communication.” The unity of sound and word awaits reception, and Bonney conjures Baraka and the image of the Changing Same in order to describe the actualization of musical energy in the present of its taking place.

It only follows that this piece means something different on the pages of Black Case than in the grooves of Song For, two separate instances of intentional return. In the recorded version of “Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City,” Jarman's text blends the musical accompaniment such that it becomes difficult to enforce a split between voices. The recitative emerges from the same breath as the instrumental, and when the saxophone re-enters after the first of three sections—a shriek chased by silence, followed by frantic trills—it feels as though Jarman is collaging the moods of the “sidewalk heroes” he extols, a spatial approach to phrasing that corresponds to the city as a means of sequester: “once quiet black blocks of stone/encasements/of regularity.”

On the page, without instrumental accompaniment, the poem feels less agitational dérive than elegy. Jarman stages a politically troubling scenario, obverse of the collective independence aesthetically mandated by Cage, choosing to construe the city as a space of abutting isolation:

non-cognitive – these motions

embracing sidewalk heroes

the city each his own

where no one is more alone than any other

moan, it’s the hip plea for see me, see me, i exist

exit the tenderness for power/black or white

no difference now/the power/city

Each of the poem’s hero-aspects inhabits a city of his own associations, but in this state partakes of a common plight. The subjective moan, whose open vowel threads this stanza, expresses the identity of one soul with another in spite of their isolation, interchangeable in anonymity, while as a “hip plea” registers a cultural idiom corresponding to the reality of racial segregation and the necessity of liberation. In the particular setting of this poem, the latter program remains inchoate, as its participants are held apart from one another: “internal/these states on planes/farout as what these lives become.”

This distance in proximity little resembles the ideal conditions for artistic creation but depicts a profoundly alienated world, the denizens of which remain, to compare Baraka’s 1956 novel The System of Dante’s Hell, “divided in their vagueness.” Addressing himself to “the hell/of where we are,” Jarman’s bleakest offering reads well alongside Baraka’s more nihilistic tracts, evoking the abstract negativity of Dada amid “vain landscapes” of the city. This vividly depicts the exile Jarman aims to overcome through his anthology, as the atomized cohabitation that the poem describes falls considerably short of the collective identity that Jarman elsewhere praises as a vehicle of return. Nevertheless, this is a necessary moment in the development of a socially concerned art form. Music, as Baraka writes in parallel to the poem’s mise-en-scène, “summons and describes where its energies were gotten. The blinking lights and shiny heads, or the gray concrete and endless dreams.”

*

All the more reason, then, to emphasize the poem’s delayed arrival in the 1977 sequencing of Black Case, which places this lyric hopelessness amid the forthrightly affirmative manifestoes of the AACM, as though to suggest the necessary arrival of the Black avant-garde that this earlier work prefigures. Thus “Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City” appears before a manifesto of political and spiritual purpose:

Thus we unite, say AACM

GREAT BLACK MUSIC POWER

and we act; To make our dreams

realities.

The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians was convened in 1965 in Chicago by a group of Black musicians in order to “(reconceptualize) the discursive, physical, and economic infrastructures in which their music took place,” according to scholar and composer George Lewis. In his magisterial account of the group’s history, A Power Stronger Than Itself, Lewis describes how the AACM emerges as part of a larger tendency toward communalism, with the specific aim of promoting original music by its members, thus formalizing the program of liberation outlined in Jarman’s work. “We understand that/the music we play is difficult for/many to hear, but we also understand/that many other people want/and need to hear it,” Jarman writes, a modest outline of their further aims. “We want only to have/equal right to sing a great/music, just as other men…”

To this end, the AACM vigorously renarrates so-called jazz as Great Black Music, overwriting a name that is already racially coded with tremendous specificity as to its import and provenance. In this descriptive gambit, the AACM protect their own music from commodification (where “jazz” reduces a lived idiom to readily duplicated operators of style) by asserting its relative autonomy as art. One might read this polemical rebranding in light of Baraka’s points above, where Great Black Music supersedes the jazz style that it nonetheless precedes as essence, rendering Cage’s opprobrium merely parochial in its fixation.

Thus when Jarman writes of how “people who make themselves critics forget the responsibility they have to the music,” he not only addresses the commodification of jazz, but the obfuscation of its sociality and predication as Great Black Music. Responsibility to the music denotes respect for its executors, and Jarman oscillates from abstract generality to cultural particularity in decrying those who “get off trying to create destruction among the musicians by creating non Black Music images and false mask to put over the realities of the Soundmovement … BLACK MUSIC IS BLACK MUSIC and always will be.” The spiritual stakes of this undertaking play out between false opportunities, “lame gigs” and scarce funding—all the small scenes of dispossession that accrue to something like a vast conspiracy against working musicians.

Soundmovement, in Jarman’s vocabulary, is singular and collective, the tissue and material on which the artist trains, embodying spirit. “God comes to us in the sound of music and in the feeling of warm hearts bodies close together,” he writes, harmonizing with Baraka, who writes: “Identification is Sound Identification is Sight Identification is Touch, Feeling, Smell, Movement.” As sound exceeds and extends fantasmatic bodies, music enacts a corporeal blur. From Jarman’s recommendation of Aikido and martial arts—further ways in which to “train (trane)/for reality”—to the life-giving light of the sun and the doctoring rites of a people, a dialectic of distance and commonality, closeness and difference, figures multifariously throughout this writing:

-is it culture only the knowing the unknowing only

that keeps us myself and them so much away

from each other/the sound, the dear sound flowing through

each and every one of us so warm…

In this passage, sound is a common good that circulates amid community. Jarman’s conviction as to the social propensity of music produces many such endorsements of sonic universality, but never in generic guise. “We SURVIVE for the spirit of GREAT BLACK MUSIC and for the spirit of GREAT BLACK MUSIC alone. Otherwise the great gray haze would overtake us (all humanity) and we would vanish, into what we are already-Light.” GREAT BLACK MUSIC, to preserve Jarman’s emphatic orthography, furnishes an historical instance of the healing power of sound, and a path of spirit in this world.

Yet Jarman suggests that Black artistic achievement redeems “all humanity,” as a vehicle of survival for its practitioners and as a clarifying force against the “great gray haze,” a figure of colorless foreclosure, in which everyone—a telling parenthetical—would vanish without joy. As a writing of return, Jarman’s celebration of Black art traverses the terrain of exploitation and appropriation, to offer music as a gift to the world. This program is further expounded in an episode from an original mythology, where Jarman describes the bearing of the visionary ODAWALLA:

ODAWALLA came through the people of the Sun

into the grey haze of the ghost worlds

vanished legions, crowding bread lines…

This scene of immiseration echoes the serial (in)equality described in “Non-Cognitive Aspects of the City,” but its fantastical setting produces a rich allegory of the poet’s purpose. Odawalla appears to name the identity of sound and silence, word and music, image and message, that Jarman restates in so many registers throughout this anthology: an icon of new music and ancestral precedent, canceling present confusion. The figurative richness and representational cast of this poem furnish Jarman and company an origin story, while restating the political critique above in a mythological register. In so doing, it embodies the vocation of the Art Ensemble and their fellow travelers:

to guide the people of the Sun as they

seek to leave, seek to leave, seek to leave, seek to leave

the grey haze

*

We Are On The Edge: A 50th Anniversary Celebration

Art Ensemble of Chicago

Pi Recordings (Apr. 2019)

A highlight of Jarman’s writing, the story of Odawalla names a composition by Roscoe Mitchell for the Art Ensemble of Chicago—a snaking, descending melody above a deceptively languid groove, subject to variation over decades. Likewise, one understands from journeying amid the contents of Black Case that the poems reproduced here are subject to alteration by life, that they are part of a life by which poetry and music have been improved.

The Art Ensemble of Chicago celebrated its fiftieth anniversary last year with a concert dedicated to Shaku Joseph Jarman and his previously departed brothers Lester Bowie and Malachi Favors Maghostut. As a true ship of Theseus, their present lineup is augmented with a roster of newly established players, introduced by Roscoe Mitchell during “Odwalla/The Theme” in a ritual roll call, such as concluded many concerts through the years. This vocally embellished version sounds absolutely fresh, a twenty-first century spiritual jazz that demonstrates what Jarman calls the “new-old” sound, a place of circular departures, some parts changing, some the same. While instrumental, Jarman’s words continue to elucidate this melody, as any teacher lives through the attainment of their pupils, and as any body that is music lives in song. In light of this ghostly continuance, the lyrics and manifestoes of Black Case remain in their suggestiveness and vision, cutting through the grey haze of exile and beckoning return.

Cam Scott is a poet, critic, and non-musician from Winnipeg, Canada, Treaty 1 territory. His books include WRESTLERS (Greying Ghost, 2017) and ROMANS/SNOWMARE (ARP Books, 2019). He is artistic director of send + receive, an annual festival of sound based in Winnipeg.

Banner image: Art Ensemble of Chicago. Image subject to copyright.