“An unimaginary landscape that exists in a real unreal world”

Bob Kaufman was, it’s often said, a poet of the streets, a poet whose life and work manifested a deep knowledge of its nooks and crannies, its hustles, its dogged, imaginative techniques of survival, and its flashes of surreal poetic clarity. The street is a place of protest, but also of homelessness, of addiction, of those cast outside without access to shelter, property, labor, the legitimized forms of social life. In moments of social unrest, the street comes alive, as autonomous zones are established and the police—that permanent army of occupation—are pushed back. But the street is also where the crowd splinters into many voices, heard and unheard. Like so much of the life of the street, Kaufman’s work has fallen through the cracks. In his lifetime, Kaufman published just three full-length books: Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness (1965), Golden Sardine (1967), and The Ancient Rain: Poems 1956-1978 (1981). Kaufman lived a peripatetic existence predominantly around San Francisco’s North Beach bohemia, with a spell in New York’s Lower East Side. He died at the early age of sixty in 1986.

Kaufman preferred to recite his poetry in coffee shops, bars, or on the street rather than publish it in print. All three of his collections were compiled by editors from the scraps, written and oral, he left lying around. Kaufman deliberately cultivated marginality, yet he was also marginalized—subjected to forced electroshock treatment, harassed by racist police, penniless, and virtually homeless. In his later years especially, Kaufman existed on a kind of periphery, a ghostly figure glimpsed on San Francisco street corners or in North Beach bars, boisterously living out his poems. As he wrote in “Jail Poems”:

Someone who I am is nothing.

Something I have done is nothing.

Someplace I have been is nowhere.

I am not me.

Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman

by Bob Kaufman, with a foreword by devorah major

Edited by Neeli Cherkovski, Raymond Foye, and Tate Swindell

(City Lights Books, Nov. 2019)

Reviewed by David Grundy

Born in 1925 to a family of thirteen siblings, Kaufman grew up on Rue Miro, New Orleans. Kaufman’s family tree includes a German-Jewish grandfather who’d converted to Catholicism and a grandmother who supposedly practiced voodoo, and he proudly embraced this dual Afro-Jewish identity. His upbringing belies the myth of the sui generis outsider artist that later sprang up around him. His mother was a schoolteacher who made her house a center of political and artistic discussion, and Kaufman was writing, reciting, learning from early on. In his late teens, Kaufman signed up to the Merchant Navy, shortly after the United States had entered the Second World War. As Raymond Foye notes in his afterword, “the U.S. Merchant Marines suffered the highest rate of casualties of any service in World War II, with over fifteen hundred ships sunk.” One voyage saw Kaufman’s feet permanently damaged by frostbite. Kaufman soon became a member of the National Maritime Union (NMU), which, unlike many racially discriminatory unions, had a large Black membership, and a photograph from NMU newspaper The Pilot, reprinted in this new Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman, captures Kaufman addressing a rally as part of an NMU sound truck campaign. The Pilot also published a letter from Kaufman denouncing “the present hysterical campaign against the Communist Party” conducted by Senator Joseph McCarthy’s newly-formed House Committee on Un-American Activities. The NMU was badly affected by the union-busting tactics of the McCarthy era, and many radical members were hounded and expelled. This included Kaufman, who was under FBI surveillance until 1970.

Adrift from the union, Kaufman experienced his first marriage break down. He maintained a nomatic existence between California and New York. Donald Kaufman suggests that his brother’s spontaneous poetry recitals had attracted notice in San Francisco by the early 1950s, but it was in 1957, when he returned to the city, that he rose to prominence amongst those soon to be dubbed “beatniks”—a term reputedly of his own invention. Kaufman later told Raymond Foye, “I feel at home in this neighborhood […] When I’m lost and alone, and Paul Robeson is singing the Soviet national anthem in my head, and I can’t sleep, I go out and walk these streets, and I feel at home.” Transferring his politics from union activism to the anti-bourgeois rejection of normative, “square” lifestyles, it was Kaufman of all the Beats who perhaps lived the Beat ethos to its fullest: committed to spontaneity, resistant to writing down his poems, and steeped in a relentless experience of social marginalization. Having been beaten by racists while working as a labor organizer in the South, Kaufman had been rendered deaf in one ear and lost several teeth. In San Francisco, he was targeted by racist police riled by his non-conformity, his interracial marriage to Eileen Singe Kaufman and outspoken politics. James Baldwin would declare in 1964, “there is no moral distance between the facts of life in San Francisco and the facts of life in Birmingham,” and, in 1960, Kaufman, Eileen, and their son Parker relocated to New York, entering another Bohemian milieu around the so-called East Village. Kaufman was friends with artists such as pianist Cecil Taylor and poet John Wieners. He crashed on the floor of a young poet named Ishmael Reed, fresh from Buffalo and a member of the Umbra Workshop, and his work later appeared in Umbra magazine thanks to editor David Henderson. New York was not necessarily an easier place than San Francisco: the Kaufmans moved from apartment to apartment, both Bob and Eileen spending time in Bellevue psychiatric hospital, and Bob in Rikers Island. Resolving to return to San Francisco, Kaufman was on his way to meet Eileen and Parker when he was arrested for walking on the grass in Washington Square Park and transferred to a series of psychiatric hospitals, where he was subjected unwillingly to brutal electroshock “treatment.” Released in fall 1963, Kaufman rejoined his family in San Francisco, but he had been badly affected. When John F. Kennedy was assassinated that November, he took a ten-year vow of silence, and much of his subsequent behavior may have resulted from the institutional torture he suffered. Kaufman’s life had effectively been destroyed for the simple act of walking on the grass.

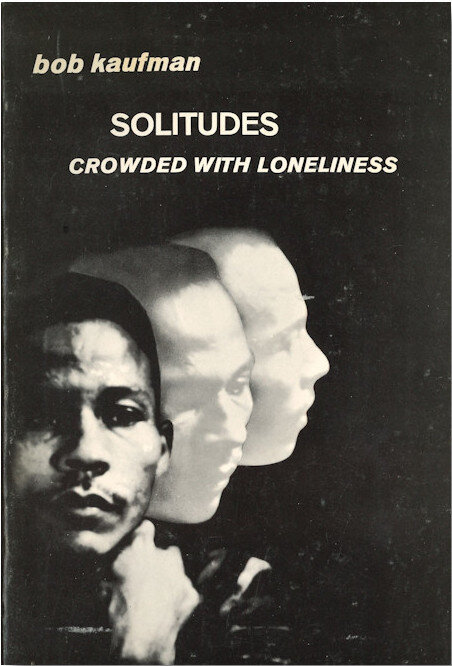

Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness

by Bob Kaufman

(New Directions, Jan. 1965)

Aside from poems in magazines like Beatitude, which he co-founded in 1959, Kaufman’s first publications were broadsides from City Lights Books: the Abomunist Manifesto and Second April in 1958, followed by Does The Secret Mind Whisper? in 1959. Eileen’s largely unheralded role in editing his first full-length manuscript, Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness, should not go unstated. She transcribed his orally-delivered poems, which were collected on napkins, matchbooks, and paper sacks, all while raising their son Parker virtually alone. Likewise, it was Mary Beach whose French translations of Kaufman’s work gave him the respect in France he was never accorded in America, and who was responsible for editing his second volume, Golden Sardine. Without Eileen Kaufman and Leach, we might not be talking about Kaufman at all. It’s largely thanks to the efforts of women, and the advocacy of Black writers and critics such as Barbara Christian who valued Kaufman’s work, that he is slowly being restored to his rightful place in the overwhelming white, male narrative of “Beat” writing to which we’re accustomed.

Moving beyond the lifestyle protest of the Beat movement, Kaufman’s work struck a chord with an emergent generation of younger Black poets. In 1969, actor Vinie Burrows recited his poem “Benediction” at the Pan-African Festival in Algiers. Kaufman’s poem sardonically addresses the apartheid regime of the American South, echoing the “We Charge Genocide” petition presented to the U.N. by Paul Robeson and William L. Patterson in 1951, as well as the well-worn trope of Israel’s enslavement in Egypt.

Pale brown Moses went down to Egypt land

To let somebody’s people go.

Keep him out of Florida, no UN there[.]

In his magnificent late poem “The Ancient Rain,” Kaufman associates Blackness and freedom with American history through the figure of Crispus Attucks, the first man to die in the American revolution, a “martyr” to the cause of American liberty who was also Black. But in “Benediction,” America is seemingly irredeemable: a zombie nation intent on spreading death both within and without its borders, from Hiroshima to Florida and Dawson, Georgia. Mockingly, “Benediction” concludes:

Your ancestor had beautiful thoughts in his brain.

His descendants are experts in real estate […]

You must have been great

Alive.

Burrows’ recital of “Benediction” in Algiers suggests a confluence with Pan-Africanism and Black Internationalism, and “African Dream,” the second poem in Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness, recalls the work of Négritude writers and Afrocentric jazz artists like Randy Weston, as well as the more ambiguous address of Countee Cullen’s “Heritage.” Evoking “strange forest songs, skin sounds […] songs / Of an ancient love,” Kaufman’s vision echoes tropes of primitivist fantasy—incongruous tigers, “incestuous yellow flowers,” “moon-dipped rituals,” and “ebony maidens.” A “memory world,” “drummed” and “hummed,” this Africa is an invented no-place existing in the apocryphal mind’s eye/ear. Kaufman’s Africa remains a hallucinated, unreal world. Yet, as a Surrealist, he trusted the visionary truth of hallucination more than the “rational” disguise of waking life, in itself concealing irrational, racist violence of unbelievable brutality.

In “I, Too, Know What I Am Not,” Kaufman riffs off Langston Hughes’ “I, Too,” through negation rather than affirmation.

No, I am not deathly wishes of sacred rapists, singing

on candy gallows […]

No I am not whisper of the African trees,

leafy Congo telephones.

No, I am not Leadbelly of the blues, escaped from guitar jails.

No, I am not anything that is anything I am not.

Weaving a genealogy both real and imagined, Kaufman creates an adopted family of artistic kinship which knows neither racial nor geographical boundaries. His grandfather joins Hart Crane, Apollinaire, Garcia Lorca, Picasso, and Kathe Kollwitz: a syncretic collective of visionaries, suicides, outcasts, and fighters against injustice brought together in the magical, life-giving space of his poems. Kaufman’s is a way of thinking about artistic tradition as alchemical transmutation, turning personal and historical trauma into a force of liberation. The extraordinary “Blues Note” sees Ray Charles as both Moses and the offspring of Bessie Smith, dying on the road in a segregated state.

He burst from Bessie’s crushed black skull

One cold night outside of Nashville, shouting […]

He separated the sea of polluted sounds

And led the blues into the Promised Land.

For Kaufman, jazz and blues counter the absurd violence of American racial aggression, from Nashville to Hiroshima, and the spectacular hypocrisy of the Culture Industry (“Hollywood, I salute you, artistic cancer of the universe!”). In “Battle Report,” “the city falls” when it’s infiltrated by “one thousand saxophones,” combining the Fall of Troy with the Battle of Jericho. But jazz is not only a tool of resistance. In “War Memoir”—printed in different versions across all three of Kaufman’s books—jazz enables white listeners to pronounce their Black fellow-citizens human, thus affirming their own humanity and making the guilt of inhuman violence bearable. While American cultural diplomacy presented jazz as a model of American liberal democracy, African-Americans were systematically exploited, brutalized and subjugated at “home.” White America, as it still does, used the defiance, pleasure and pain encoded in Black music to assuage its guilty conscience, to draw from its energies, and to fulfill a primitivist fantasy into which it projects all those elements excluded from the ideals of the Protestant Work ethic, the bootstrap ethos, and moral conservatism. Yet this music still testifies to survival in the face of genocide. Positional, improvised, and contingent, jazz serves as a useful figure for Kaufman’s poetic method as a whole, its apparent looseness belied by a sustained tension that sustains imaginative flight yet also attests to terrifying claustrophobia, in which freedom and spontaneity face the whims of doctors, jailers, and cops. In “Jail Poems,” Kaufman writes:

In a universe of cells—who is not in jail? Jailers

In a world of hospitals—who is not sick? Doctors

A golden sardine is swimming in my head

Oh we know some things, man, about some things

Like jazz and jails and God.

Saturday is a good day to go to jail

Kaufman’s second book, Golden Sardine, opens with a long poem for Caryl Chessman, a Death Row inmate whose case had been a cause celebre since 1948, and who was executed in 1960. In Kaufman’s infernal vision, Chessman is at once Dante, Virgil, and one of the victims they pass in the circles of hell, as Chessman’s execution merges with that of “the last Buffalo in Nebraska,” “DEAD IN THE MAKESHIFT GAS CHAMBERS OF SUPPRESSED HISTORY”:

[…] CARYL CHESSMAN WAS AN AMERICAN BUFFALO, &

OUR VOMITING ASSASSINS KILLED HIM, & DESTROYED THEM-

SELVES IN THEIR REPUBLICAN-DEMOCRAT HASTE TO EXTIN-

GUISH HIS BURNING […]

Golden Sardine

by Bob Kaufman

(City Lights Books, June 1967)

Such works, threaded through with jittery anguish and a bitter, spiky humor, are powerful yet brittle as a spinning glass top. Kaufman forces the English language to reveal the secrets hidden beneath its lexical meanings through disjunctive juxtaposition, grasping at the fragments that rush past in associative, seemingly improvised streams of word and sound. In probably his most famous work, the Abomunist Manifesto, Kaufman reinvents himself as “Bomkauf,” author of a manifesto without a program for a movement without a movement, a joke about sensationalist labeling of the “Beat” generation (the Manifesto comes complete with a dictionary of pseudo-slang), news coverage, pseudo-philosophy, and religion. “Bomkauf” places the bomb in his very name: from anarchist bombers to white supremacist terrorists and the Atom Bomb, Red Summers join Red Scares amidst the threat of global annihilation. Nightmare shadows humor in a vertiginous balancing act. Constructed as one unbroken, six-page sentence, Does The Secret Mind Whisper? goes further. Removing any kind of organization by paragraph, line or sentence unit, it applies a kind of unbearable pressure to language from which it seems it might explode—or fall silent.

Golden Sardine ends with a letter written to the San Francisco Chronicle on Kaufman’s return to the city in 1963. In effect announcing his vow of silence, the letter signifies Kaufman’s status as a forgotten member of the Beat Generation, an African American political radical subjected to the “Blacklist” in its multiple senses, jailed and shocked, categorized and ignored. Kaufman turns his social marginality into a position of quiet strength. Echoing Emerson’s “different drummer,” he announces himself to be “the silent beat in between the drums” which “drowns out all noise.” Read this way, Kaufman’s decade-long silence is a subversive act and tool of survival as well as a reflection of damage. When the United States declared the end of the war in Vietnam, Kaufman burst into poetry once more, though his attitude to manuscripts was still neglectful. Raymond Foye recalls rescuing the majority of the work for The Ancient Rain from Kaufman’s burned-out room after a disastrous fire at the ironically-named Dante Hotel.

Kaufman’s post-silence poems often appear in capital letters, like telegrams, news reports, rants. Declarative and urgent, their tone of political prophecy draws on a wide sweep of American history, merging personal trauma, political horror, and imaginative genealogy with hallucinatory, sur/realist power. In “Blood Fell on the Mountains,” an earlier poem written the week after Kaufman’s 1963 return to San Francisco, we come across the first instance of the phrase “crackling blueness,” a variant on Garcia Lorca’s azul crujiente which resounds through a number of later poems. “What did I do to be so black and blue?” sang Louis Armstrong, a pun crackling with racialized irony. Likewise, for Kaufman, the association of blue(s) and blackness merges memory of personal trauma—whether electroshock or a memory of being hung up by the thumbs by a racist mob—with an indomitable life instinct. “[THE NIGHT THAT LORCA COMES]” is an Afro-Futurist journey, echoing William Melvin Kelley’s 1964 novel A Different Drummer along with Lorca and Sun Ra, in which the North is not so much physical location as a fugitive utopia, alive in the poem’s alternative universe.

THE NIGHT THAT LORCA COMES

SHALL BE A STRANGE NIGHT IN THE

SOUTH, IT SHALL BE THE TIME WHEN NEGROES LEAVE THE

SOUTH

FOREVER,

GREEN TRAINS SHALL ARRIVE

FROM RED PLANET MARS

CRACKLING BLUENESS SHALL SEND TOOTH-COVERED CARS FOR

THEM

TO LEAVE IN, TO GO INTO

THE NORTH FOREVER […]

As Ray Charles bursts out of Bessie Smith’s crushed skull singing the blues, so “crackling blueness” transmutes personal and collective trauma into a force of artistic beauty and power.

The Ancient Rain: Poems 1956-1978

by Bob Kaufman

(New Directions, June 1981)

In these poems, Kaufman sketches out an alternate space, “IN BETWEEN BETWEEN, BEHIND / BEHIND, IN FRONT OF FRONT, BELOW BELOW, ABOVE ABOVE,” a space which “BEGINS AT THE BITTER ENDS,” “AN UNIMAGINARY LANDSCAPE THAT EXISTS IN / A REAL UNREAL WORLD.” This vision is neither strictly utopian nor dystopian. In “The Ancient Rain,” “the source of all things” which “knows all secrets” and “illuminates America,” simultaneously cures plague, destroys empires, Hollywood, the Ku Klux Klan, and genocide. An ambiguous force, it’s unclear whether the Rain signals war or peace, global catastrophe, or the emergence of a new social order. Kaufman’s poems speak to the compressed potential of history to explode like a powder keg, as Baldwin put it, sometimes when you least expect. Crispus Attucks, hero of “The Ancient Rain,” was an African American man fired on by militarized colonial authorities while peacefully protesting on the street. Sound familiar? Likewise, the Bomb that haunts Kaufman’s earlier work is still the ticking time bomb on which humanity lives, we just don’t talk about it anymore. But poetry has always troubled the deathly givens of “common sense.” Beaten, jailed, and subject to electroshock, Kaufman lived out the reality of racial terror in his body. Yet he turned his status as marginalized outsider into a condition of freedom. Kaufman’s poems are a series of contained explosions of the psyche, of the social, of the poet and the people “spread-eagled on this bone of the world.”

“So be it. Let the voice out of the whirlwind speak.”

David Grundy is the author of A Black Arts Poetry Machine: Amiri Baraka and the Umbra Poets (2019) and is co-editing the Selected Poetry of Calvin C. Hernton. He lives in London and is a postdoctoral researcher at Warwick University.

Banner: Bob Kaufman. Image subject to copyright.