The following exchange was conducted over email with John O’Brien, founding publisher of Dalkey Archive Press, Review of Contemporary Fiction, and CONTEXT, in August 2009 for a defunct blog that was briefly maintained by Music & Literature editor Taylor Davis-Van Atta. It is reproduced here, unedited, largely for posterity.

Let’s start with the value of building a reading knowledge that extends beyond American writers. By my calculation, U.S. authors constitute only about 40% of the Dalkey library, which, if you believe assumptions in the publishing industry, is a model doomed to failure. As much as commercial publishers deny it, there is in fact a curiosity and interest among American readerships to learn more about other countries and international writers. On the individual level, what is the importance of reading literature that is coming out of other places in the world?

I will answer this as an individual rather than as a publisher. My serious reading began in high school and began rather indiscriminatingly after asking my freshman English teacher for a list of books that I should read. At the top of the list was Dostoyevsky. So, I began with a work in translation but of course did not think of it as “a work in translation.” Like most readers, I think, it was a novel, and it didn’t matter to me that it was a translation, nor did it matter to me that I couldn’t pronounce any of the characters’ names, nor that I didn’t know very much about Russia except what was in the news about the Cold War.

I suppose that this early reading influenced me a great deal and directed me to writers throughout the world. So, I started with an international perspective, but without any intention of doing so. I just wanted to read the “great books” and do with them whatever a mixed-up, confused teenager does under the influence of reading literature, which usually results in getting more mixed-up and confused. But that’s another subject.

I have never made much of a distinction between a novel written by an American and one written by a writer from another country. To use Henry James’s norm, the work is interesting or it isn’t. My random reading habits from years ago brought me to read a great deal in translation, especially in French literature. And this reading gave me a certain perspective with which to read American and British literature.

My view is that literature is an international art form and that any serious reader needs to read a novel, for instance, in light of all other novels if one is to gain the full benefit of what a particular writer or work is up to. I like fiction that is doing something different from what I have seen before, this is the kind of fiction that delights me, even though it may also elude me in many ways. It’s not just that great literature can come from almost anywhere, but to appreciate and enjoy a particular work means, I think, that you are reading it against the background of so many other works. But this is true of the other arts as well. The more you have listened to music and the more that you know about it, the greater is the pleasure. And of course with music or painting, one doesn’t say, “Oh, Bach is German, how can I possibly listen to him since I’m an American?”

My point here, if I have one, is that readers do not care whether a novel was originally written in English or not. Unfortunately, various people in the publishing industry do care because there a deep-seated view that readers are put off by books written in another language, and so with this belief in hand, translated literature tends to be less reviewed and less stocked in bookstores, and thus publishes tend to do fewer books in translations. None of this thinking seems to apply to the classics, though. Homer, Cervantes, and Flaubert are almost thought of as “English-speaking writers,” but their contemporary equivalents inhabit another category wherein they are perceived as “difficult, foreign, unapproachable” by the average reader. But I do not think the problem is with the reader.

I have read a handful of articles just over the past year, many written by the editors of lit mags, in which blame for low subscription numbers is laid on the reading public (or what these editors fancy their public to be), and it was the perpetuation of this belief that American readers are disinterested and lazy that motivated me in part to host this series of interviews. It seems to me that the disconnect between a literary endeavor and its intended public arises because the product being offered is no different than scores of other products on the market, which is not to mention the issue of ineffective marketing. But the distasteful assumption underlying these articles is that the publication itself, along with its business model and its editor, is without flaw. Dalkey sports an impressive readership and one of the issues I want to tackle with you is how the Press courts and grows that readership, but for now I’m wondering what shortcomings you see in your press in terms of its efforts to put the right books in the hands of the right readers. What are the biggest challenges for a press that offers a unique aesthetic?

A follow-up question might be something like this: I imagine that seeking out independent booksellers that are willing to take risks in what they carry is important for Dalkey. How do you connect with those sellers?

Once again you have gone right to the heart of the issues, and there is no simple answer. Dalkey was more or less founded on the principle that there are great works of literature that the marketplace had already given up on. For the first few years, all that I was publishing were works that had gone out of print, and authors whom bookstores and critics and academics were ignoring. So, the Press’s mission was, by its nature, un-commercial. And yes, there was my belief that I was publishing books that “one day” would find their audience if kept in print. But this is also true of most of the original books that we have done, books by authors who were either not known in this country or authors that, despite the recognized artistic quality, were seen as appealing to few people.

So, it has always been an uphill battle of sorts, recognizing the obstacles that we faced and dealing with them as best we could. But we also knew that we were doing something very different in publishing, and in some sense we were not a publisher in any conventional sense. Remember that before the Press there was the Review of Contemporary Fiction, which I created in order to give critical attention to writers who were being overlooked (another grand un-commercial project!). I knew that there was little interest in these writers, but I wanted to change that. The Press came out of the same spirit.

Have we done an adequate job of “marketing” over the years? Yes and no. When you are trying to market what the marketplace already sees as un-marketable, good luck! Most publishing houses begin on the opposite principle: that there IS a market for certain kinds of books and that’s what you will supply to the marketplace. I began the Press with a contrary view: these are the necessary books and authors, an audience had to be cultivated slowly over a period of years, and that the Press would always have a relatively small, if important, audience.

And of course there are the financial realities that come to bear. If the Press had more money than it knew what to do with, I would prefer to give books away at no cost: how much more un-commercial can one be? The point is to get them read and talked about. But in a country the size of the United States, how do you reach this “small” audience? James Laughlin, the founder of New Directions press, and I used to talk about the potential size of the audience for out kinds of books (New Directions and Dalkey). James said that the audience used to be about 50,000, but it was now 30,000. I said that it was still about 50,000, not that there were 50,000 for each book or that one could reach all of those on any given day. It was amazing to me that we both seemed to be working with about the same imagined number.

I realize that I am going on here at great length. Dalkey does pretty much what all other publishers do: meet with reviewers, try to get as many reviews as possible, work with stores in a variety of ways, know the stores well, send out a large number of galleys and review copies, follow up with reviewers and stores, and so on. And of course there are other markets as well, such as individual orders, special sales to individuals, libraries, and classrooms. And because we are also located in London, the European market is increasingly important to us. And now that we are being distributed by Norton, we will also be reaching stores throughout the world.

But all of these market efforts still take place within the context of our doing a certain kind of literature, while also recognizing that being dedicated to literature generally is rather specialized to begin with. And I will still say that the audience is about the same size as what Laughlin and I speculated it is. For our kinds of books, that size seems to be impervious to change, regardless of television, movies, or the internet.

Let’s talk a bit more about reviews. You mentioned earlier that works in translation are less often reviewed in this country than work by American authors. There are a handful of lit journals that set aside a few pages of each issue for reviews, but the main difference I’ve noticed between Review of Contemporary Fiction and those publications, as well as established reviewers such as NYT, Washington Post, LA Times, etc., is that there is an effort made by RCF reviewers to contextualize new work beyond the typical “reminiscent of Hemingway/Cheever” comment you find in most reviews. Reading RCF, one most often feels as if the reviewer is not only well read but also has an understanding of literary forms and the ways in which a particular author is playing with our expectations—not in terms of plot twists, or surprising character revelations, but in terms of our expectations of the novel form itself, how a novel “ought to” read. This is very much in keeping with the aesthetic of the press, this focus on the reinvention of form. I realize this is a broad topic, but to your mind what is the function of literary book reviewing in American today? And what should that function be? Are there book reviewers that you frequent, that you trust who are not affiliated with RCF? In short, I guess, what should a good book reviewer attempt to convey in his/her review of a new novel, regardless of its country (or time) or origin?

You keep opening one can of worms after another! When I started the Review, I wanted the book-review section to take strong positions, to say “this is good and why” or “this is bad and why.” Unfortunately, there are many mediocre reviewers out there who are willing to be nasty for all the wrong reasons or who have an ax to grind. So, I decided that we should just review what’s good. Even here, however, you will find reviewers who praise without reason.

But you are absolutely right in your sense that we try to talk about books from the perspective of what has come before. I detest reviews in which you know that the reviewer does not know very much, hasn’t read very much, and is therefore coming to the present book without the advantage of—or a concern about—what has been written before. And so, yes, we try to have reviewers who can establish a context for a book, but without using this context for dismissing the book before them (as in: “not as great as Hemingway”).

I could name reviewers, good reviewers, who work for various newspapers or NPR, but I know I will miss, and therefore offend, some. But here are a few: David Ulin at the Los Angeles Times; Thomas McGonigle, who usually reviews for the Times; Bill Marx at NPR in Boston; Michael Dirda at the Washington Post. All four are professional reviewers and see their role as reviewers rather than as novelist who occasionally review books. They are all extremely well read, but are also generous, in that they try to see the book in front of them and understand what this particular book is up to. And there are some outstanding reviewers in England such as Boyd Tompkin.

Unfortunately, book reviewing in America these days is at a low ebb. Book review sections are having their space reduced or eliminated. The books that generally get reviewed are the “expected” ones.

So I think I see a paradox emerging, a conflict. I imagine in some ways you must attempt to address or even appeal to the literary establishment—those poor reviewers, the world of academia—just to get the word out about new titles since, as you said earlier, you’re not in a position to shrug off sales totals, but Dalkey stands ideologically opposed to the conventions that that establishment upholds. As a business, Dalkey opposes commercial convention, and as a library it opposes conventional aesthetic—those novels that don’t attempt to further the art of the novel. There was a line in Energy of Delusion that seemed to encapsulate what Dalkey is about, and it went something like this: “The search in literature is the search for new meaning, and it’s the frustration with old forms that lies at the heart of this search, and at the progression of art itself. There is a conflict of different needs happening.” And there seems to be a similar conflict with Dalkey Archive because, on the one hand, you have to play ball with the system that’s in place in order to sell books, yet the books you are selling undercut the assumptions that keep that system in place. Dalkey is a kind of political statement, in a way.

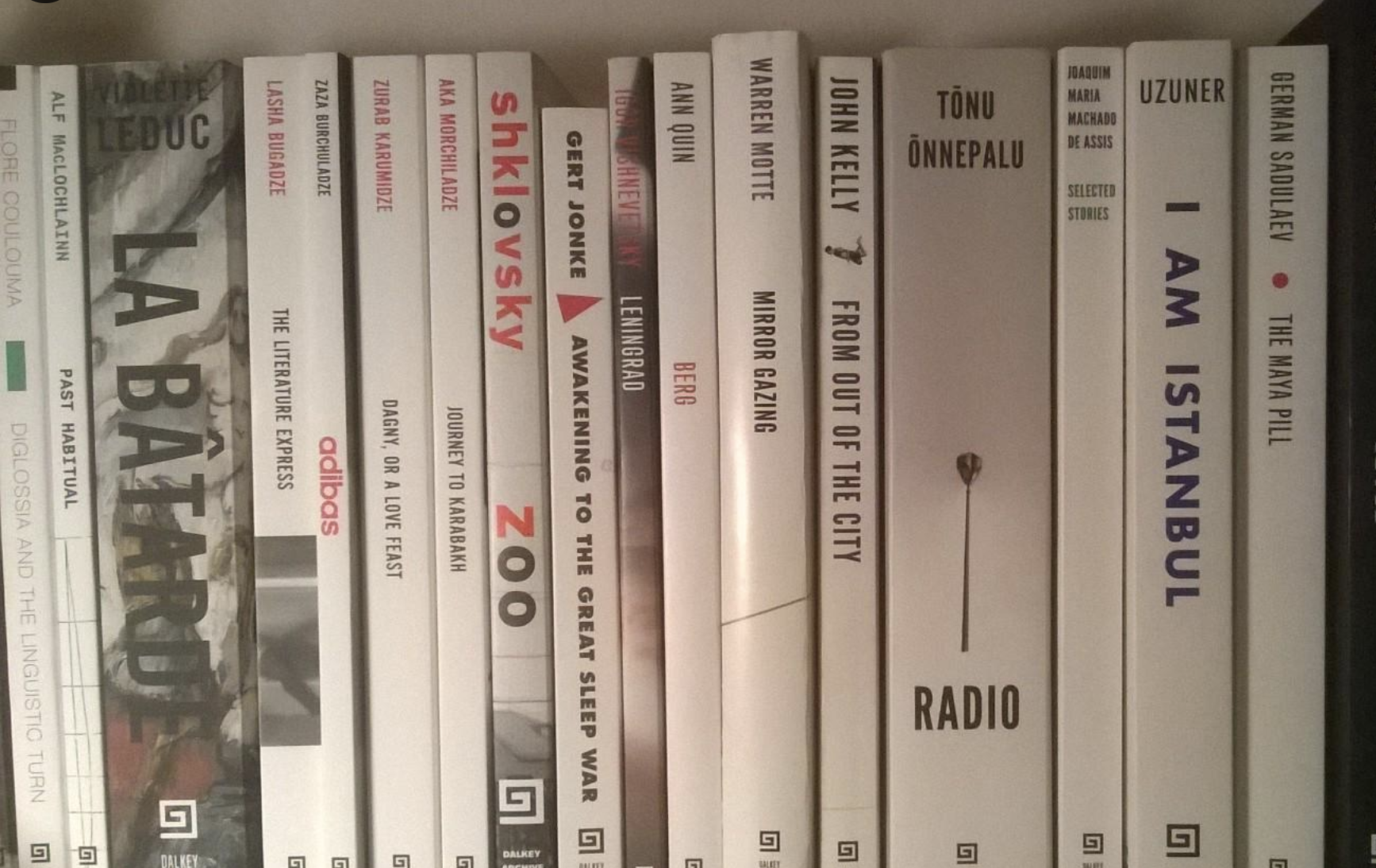

Yes, Dalkey is “a kind of political statement,” and I have said this elsewhere, but I think few people get this because we are usually seen as this very elitist publisher that is as far removed from politics as can be, much in the way that the “Russian Formalists” and Shklovsky were seen this way. One way of answering your question is to say that the mission and vision of the Press came first, and that publishing itself was just a means to fulfilling that vision. We have to straddle two worlds, as you point out. On the one hand I may object to how things are done—from how literature is read to how the media engages with it—but on the other hand the Press has to work within that world in order to reach people and to try to effect change. What is the change that I am after? I suppose that long ago I gave up on the idea, if in fact I ever had it, that the “conventions” of publishing and reception would ever change very much, and so the change had to be manifested in what Dalkey itself did. We now have over 450 books in print: books that otherwise would most likely never have seen light of day or would have stayed out of print. That act alone is a fact: the books are available, including many of Shklovsky’s books, keeping in mind that none of his critical works in print in English until Dalkey had them translated and published. And of course we have tried to create our own critical discourse through the books and the Review of Contemporary Fiction and CONTEXT.

I have always said that it’s utterly remarkable to me that the Press has survived this long because of this kind of thinking and behavior. We do stand in opposition to many things, and yet must also work within certain structures that include those things. In most ways, I have had little difficulty doing this: I know what I want for the Press and do what’s necessary to get it. This makes me what? Both an idealist and a pragmatist at one and the same time. So, perhaps the most glaring example of this is that I am glued to our cash flow statements, while also taking on books that are almost guaranteed not to help with cash flow. The balancing act there can be tricky at times. But all of this comes down to whether one knows what you want and are willing to do whatever you have to do to get it. Most people aren’t willing to do this. Years ago this meant staying up to 2 or 3 in the morning putting labels on catalogs that I would then have to bring to the post office, learn the cheapest way of sending those catalogs out, and then monitoring the response rate. All of this seems far removed from what can be perceived by others as the “glamour” of publishing, and especially the “ivory tower” of Dalkey. There has never been an ivory tower for me. The Press quite literally started in my basement and I have never lost a sense of it still being in a basement. But it is very hard to find people who have this dual mentality. A great deal of sacrifice is involved, and very hard work.

You’ve mentioned CONTEXT a couple of times and I want to talk about that next in part because it is what first got my attention and drew me to the Dalkey library, and I want whoever reads this to know CONTEXT is out there. CONTEXT, I believe, exists largely to benefit people like me, young students who are interested in the critical inquiry of literature but find themselves with little or no way of accessing that world. (For instance, I came across CONTEXT while researching the Italian novelist Elio Vittorini. The article in CONTEXT was quite a find since there is only one book in English (Three Italian Novelists, by Donald Heiney) that gives any attention to Vittorini’s body of work, and that book is quite difficult to discover even if you know what you’re looking for.) As I understand it, CONTEXT is an educational tool; it is used in classrooms. In talking with people at Host Publications, they have told me that Host relies heavy on the academic world for both sales and also for promotional purposes, namely the engagement of younger readers. Does CONTEXT help court new, younger readerships? What is the relationship between Dalkey and the academic world?

With CONTEXT, I wanted to create something that I wish I had had access to when I was 18 to 24 years old. At that time, and even much later, I was always looking for names of books and authors, and also trying to find a “context” within which to read them. So I started CONTEXT for that sole purpose: to help younger people. I will also say that I decided to make it free so that stores would carry it in large numbers rather than not carry it at all or just get a few copies that would get buried amid all the other magazines.

Your own experience is very gratifying to me because it was precisely what I hoped would happen with younger readers. But as is usual with publishers, it is so difficult to know who is ready what, or who is buying what: who are these people? How old are they? What do they do with the publication? There are ways of trying to get such information, but none of them are very good. And so CONTEXT is something of an MS in a bottle. Even though we oftentimes feature our own authors, we have never seen much of a correlation between an article about a Dalkey author and then an increase in sales. And yet we go on doing it because I think it’s the right thing to do.

It does apparently get used by certain professors, but our relationship to academia, despite our being at the University of Illinois, has been a strange one. People assume that our books must get used widely in classrooms, that they are “those kinds of books.” But in fact, they are the kinds of books that don’t fit neatly into most courses. When I started the Press, and then CONTEXT, I knew that academics were not the audience. As far as we have been able to determine over the years, our audience is younger people who more or less discover on their own, usually in bookstores. Beyond that, the audience is the so-called general reader. All of this flies directly in the face of the belief that younger people aren’t reading literature. But my belief is that there is a core group that will always be reading our books, and the core group is mostly young.

Finally, I will say that we did a survey with academics about fifteen years ago in which we asked which contemporary writers they taught. There seemed to be a very close relationship between the New York Times best-seller list (do remember that this was fifteen years ago) and what was taught. The conclusion that we drew was that academics, like everyone else, was greatly influenced by “what they heard about” rather than by what they found on their own. I myself was a typical academic when I used to teach, and would tend to search out the unusual writers who were not well-known. But apparently I was something of an odd-ball in this and many other ways.

As I was pecking out my last response I could only imagine there was some contention or friction between Dalkey and the academic world, given the decline of literary criticism and theory in this country over the past three decades. Can you talk about the relationship between academia and the field of literary inquiry as it stands today, and as opposed to how it stood, say, thirty or forty years ago? Is it a cultural change that has led to this decline, or a change in how publishers thought about marketing lit crit/theory, or is the decline in this field purely a result of declining sales?

What this is all leading to, if anything, is a discussion about how changes in academia and the corporatization of publishing have affected the enduring power of new literature that comes out, and the way in which our culture processes literature. I think it’s important, for one thing, to keep in mind that big, corporate publishing is an advent of the past 50-100 years, and before that everything was “independent” or self-publishing, but let’s wait to get into that and just stick with academia.

With whatever I say, please keep in mind that I was a professor for many years, and even a department head for many years. So, I was knee-deep in the academic world, and the Press has been on a campus for many years. So, my remarks are from the inside of this world.

When I was an undergraduate, I tool a course in contemporary American fiction: twenty years later, I looked up this course in the university catalog and its description hadn’t changed! So, there, that’s emblematic of what I find wrong in academia.

Beyond this? The world of academia, for the past several years, is run in a corporate-like way, but not run very well in this way. Trying to do new things is very difficult because, well, they haven’t been done this way before! Which is a way of saying that schools are often run as though they were businesses, but of course the business world has to be ready for change and adjust to it quickly, or a business doesn’t survive. Academia just plods along.

We have been very fortunate at the University of Illinois because the Chancellor here, Richard Herman, is a very different kind of administrator. He once told me, “Where some administrators see risks, I see opportunities.” That’s how we wound up at the University of Illinois, along with a great deal of help from the novelist Richard Powers.

But to try to get at your question. I do not have false memories of what academia was like years ago and what it is like today. Thirty years ago, there was more of an emphasis upon literature as art rather than as “example of theory,” but there were still formulas at work in deciding which books should be taught. There were few risks taken because professors had built careers on certain authors, and had learned how to read these authors. This led to the exclusion of a number of other writers who didn’t fit the formula, which was basically that of the New Criticism. In my last year or so of graduate school, I met Gilbert Sorrentino and more or less started my education all over again. In fact the first time I met him, he mentioned author I had never even heard of, and I asked him to make me a list. They were all authors who were never talked about in the hallowed halls: William Gaddis, Flann O’Brien, Hubert Selby, Paul Metcalf, and Douglas Woolf, to name a few. And of course Gilbert’s great passion was William Carlos Williams, whose “Red Wheelbarrow” was about the only poem ever taught in universities at the time.

As far as I’m concerned, things have not much changed. Speaking of literature as “art” is still anathema in academic circles, as is claiming that author X is more important than author Y.

The great pleasure in reading for me is to encounter books that I don’t know what to do with, books that both delight and baffle me at one and the same time. But what can a professor do with such a book? It seems to me that he should begin by saying, “I’ve read this book and don’t know what to do with it. Let’s take a look at it and start speculating.” But this then would require that you have students who enjoy this, rather than ones who want definite answers, and the American educational system is not very good at educating students to ask questions and to think.

All right, I think we’re coming down the home stretch. I was going to ask you about Gilbert Sorrentino, whose Something Said and Mulligan Stew I discovered after reading At-Swim-Two-Birds but whose name I’ve never heard said aloud during my entire academic life. Why has his work gone more or less unacknowledged in his home country? Or was he better known in the fifties and sixties? And, to get at the larger issue, how much do we rely on the academic world to bring contemporary authors to our attention, into prominence? To what extent can a writer’s reputation and ability to endure be helped along by the publishing world?

Yes, Gilbert Sorrentino, whom I consider to me America’s most important novelist sine 1950. I don’t know of any other writer who had the range and depth that Gilbert had in his fiction. With each book, he set himself a whole new fictional problem to solve; he didn’t like to repeat himself in any formal way. And of course he was a one-of-a-kind critic. He could be writing about almost anything and make penetrating, memorable comments; the closest we have to this now is William Gass.

I really don’t know why his work is not more widely read. He used to guess that critics couldn’t a convenient handle on what he was up to, he didn’t fit a formulaic scheme. And so, critics being critics, they either ignored or overlooked him. The academics were simply baffled; they didn’t know how to read him or teach him.

Gil used to say that “sophisticated” people had a harder time with his work than an academically un-trained reader. This was borne out for me one time when the person who ran the bookstore at some disreputable school where I taught, used to love to read his books, which I frequently taught his books; this woman, who might have graduated from high school, called me one day and said, “Dr. O’Brien, I’m laughing my ass off reading the Sorrentino book you’re teaching.” That was Mulligan Stew. Critics still don’t know what to do with his books. Sorrentino is a pure joy to read; he is the twentieth-century Melville, and we know how long it took Melville to get attention.

Academia and book reviewers have a great influence on reputations, but they fall under the influence of what’s hot, what’s relevant, what everyone else is reading and talking about. I believe that the New York Times gave Gil’s first two novels in-short reviews, and one of them appeared about a year after publication.

Getting into the classroom is key to a writer’s success, though Gil didn’t care about success. And this wasn’t something he said defensively, as many writers do. He simply didn’t care; his joy in writing was the writing. He felt that he was writing for himself and a handful of people. And why not? But my view is that some of his books are monuments to the art of fiction and should show many writers after him how things can be done in fiction, what the possibilities are, especially if freed from the deadly restrictions of realistic fiction.

And he is, at least in most of his books, very, very funny, though he also wrote the most depressing book I have ever read, The Sky Changes, which is about divorce, and is the only book I know of that is really about divorce. It’s an incredible book.

If by the publishing world you mean “publishers,” they can be of help, certainly by just publishing a writer and making a commitment to his work over the long run, though this is rarely done any longer unless a writer sells well. Gil’s books went out of print almost before they were published, even though his first few publishers were major houses. Most of his works are now with Dalkey Archive, as you know, and we keep our books permanently in print. His books sell slowly but steadily. But Gil also didn’t like publishers, and usually for good reasons.

You’ve talked a bit about being a professor. What, if anything, has your publishing life taught you about reading that years of professorship could not have? Do you approach new texts differently as a publisher than you did as a teacher?

This will be a quick reply. Yes, being in publishing causes you to look at texts differently, to see them as a process, an ongoing process, rather than something that God handed to someone and that this someone then handed to the publisher. When editing, you get to see the book in a very different way: you see the “insides” of it, and you also begin to see that the book and the author can be quite different from one another. It’s as though the book has a life of its own, and is oftentimes asking for things to be done with it that are not always in line with what the author (or translator) wants. There really is a sense that the book has become its own self.

In some ways, though, this is not entirely different from how I approached books before, or how I “taught” them. What interests me most about a novel is what I don’t get, what eludes me, what I don’t understand. So, that is what I used to put to students, and it would not necessarily make them comfortable because they usually wanted answers, not questions. So, typically, I would say something like, “Here is what I think Hemingway is doing, but I’m not sure. Any ideas?” The feet would begin to shuffle.

But this is what interests me about a book: how did he do this? What did he do? Why this way?

I should wrap this up, I think I’ve exhausted us both. But before I move on, I have to ask you one last question. Because Dalkey Archive is built around your personal aesthetic, what do you hope for CONTEXT, RCF, and the Press after you’ve gone? Can the press hold true to its mission without you, or will it have to remodel itself? Or, are you going to hold some sort of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory sweepstakes in order to find its rightful heir?

Once again, you’ve gone to the heart of things. The answer is really two-fold. The first is having to have a financial base that will ensure Dalkey’s future: that is an unavoidable reality. I hope that this base will take the form of an endowment that will allow the Press two things: its “best day” and protection. The history of the Press until now has been an over-dependence upon me as the founder; this situation is probably inevitable. But it has meant my having to pull a lot of rabbits out of a lot of hats, which is not a realistic plan for the Press beyond me.

But at the center of your question is something else: to what degree is the editorial vision—and so many other things—coming out of the fabric of my mind and sensibilities, and therefore what happens when I’m not around?

At the moment, I have to say that there is no clear answer to this. Publishing has a history of failure in the “second generation.” Some publishing houses become almost parodies of themselves in the second generation. Others just fold up because they can’t survive without the founder. Others change radically and have little to do with what they were all about before.

Some of this has to do with a good staff that is ready to take over, and a good board that takes on the responsibility for the future. Still, does the “character” of a press change without the typically obsessed founder spinning one idea after another? Probably.

I really don’t know what “Dalkey Archive Press” is because I think of it as a work-in-progress, and so I could not very well describe to anyone what should be done after I’m gone. I mean, the advice would be so general as to be worthless: Be inventive! Take risks! Go against the grain! Be smart! Try to do the impossible!

At times I have thought that the Press should plan to change itself after I’m gone, become something else, rather than to try to carry on a tradition. I have thought that it should perhaps become a poetry press. Do in poetry what I have tried, primarily, to do in fiction. Or become a non-fiction press devoted to social and political issues. In other words, start over, that this might be the best way of keeping a certain vision alive without just trying to imitate what I have been up to all these years. And what I am saying about Dalkey also applies to the Review and CONTEXT.

As you can tell, I have no clear plan for the future, and think that this will be left to others to decide. But a plan will have to be developed over the next few years. Even though I have a deep conviction that I will live forever and be functional, I also have a vague sense that this will not be the case.

John O’Brien was the founding publisher of Dalkey Archive Press.

Taylor Davis-Van Atta is the publisher and co-editor of Music & Literature.