I first came across the young Russian poet Galina Rymbu shortly after she posted a poem on LiveJournal the day that Russian troops started operating in Crimea, and several days after the victory of the Maidan Revolution in Kyiv and the tawdry close of the Sochi Olympics. Russian media fanned the flames of patriotic hysteria and the Kremlin was clearly going to exploit Maidan to crack down on domestic dissent. It felt strange that a work of this artistic sophistication and power could be composed and posted on the Web simultaneously with the events it responded to. Its viewpoint was that of the minuscule and very young Russian Left—roughly the same political alignment as those of the poet-activist Kirill Medvedev and of Pussy Riot, to cite figures known to some Western readers. But the poetry was different. It was Big Poetry, very much grounded in tradition but also propelling it forward, into the terra incognita of the now. It’s been a while I read a poem that felt so real . . .

On the occasion of the launch event for Issue 6 of Music & Literature Magazine at The Forum in Norwich, the British poet and Hungarian translator George Szirtes was invited to read a poem as a preface to Roman Yusipey's performance, on accordion, of the Ukrainian Victoria Polevà's Null, a composition written for Yusipey himself. Subsequent to that evening, Szirtes was moved to write a further poem inspired by and dedicated to Yusipey. Music & Literature is proud to publish both poems in their entirety . . .

A feature by Matthew Spellberg

The artist William Kent worked in isolation for half a century in order to produce a fantastical universe out of wood, slate and satin. The inhabitants of this universe included insects, sea-monsters, giant safety pins, and outsized rubber chickens. Their creator gave them shelter and purpose. In return, they helped carry out one of the century’s most radical and bizarre projects of transformation . . .

A feature by Matthew Spellberg

The artist William Kent worked in isolation for half a century in order to produce a fantastical universe out of wood, slate and satin. The inhabitants of this universe included insects, sea monsters, giant safety pins, and outsized rubber chickens. Their creator gave them shelter and purpose. In return, they helped carry out one of the century’s most radical and bizarre projects of transformation . . .

A feature by Samuel Cottell

Panichi frequently alludes to the lessons he learned from his time in the BMI workshops with Bob Brookmeyer: "Repetition and change are the most important variables in composition. The hardest thing in music is to know when to introduce change. Brookmeyer used to say, 'Keep going in a particular direction until you think you’ve overdone it; then you can go somewhere else.'"

A feature by Joanna Walsh

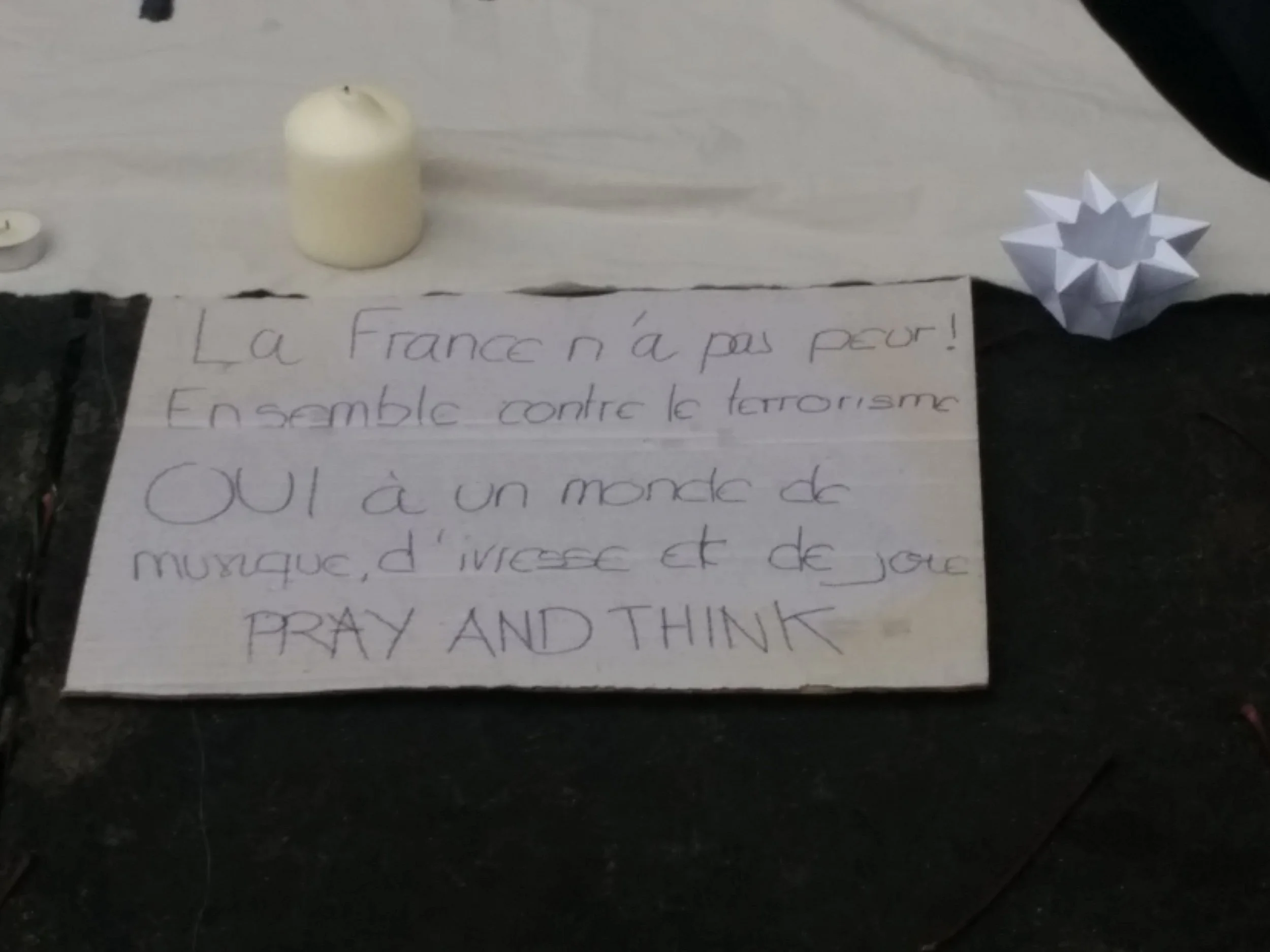

Last Sunday in Oxford I attended a vigil. Two to three hundred people, most of them French, walked from Radcliffe Square through the center of Oxford to the French Cultural Institute, La Maison Française. I stumbled my way through “La Marseillaise” (I can’t remember half the words), there was a minute’s silence, then people came forward to place, on a cloth, flowers, candles, newspaper clippings, scribbled notes, photographs, small, and sometimes unidentifiable objects. . .

A feature by Elodie Olson-Coons

. . . Being a woman conductor and being a singer who is also a conductor are rare enough occurrences individually. A woman who conducts and sings at once, in the same performances, and to rave reviews? A rara avis indeed. Watching her take on this incredibly balancing act, one is made aware once more of her sheer physical and mental strength. Her arms are another voice: trained; rippling with strength and emotion—yet another stark marker of the sheer discipline with which she approaches her work. At times, her love of a challenge seems to go even beyond discipline. Writing about the difficulties of playing Lulu, she also writes about her enjoyment of those difficulties: “It hurt like hell and I loved it,” she says of her first time in pointe shoes. “I couldn't wait to lace up every morning. I loved that a doctor had to come to my dressing room after the second performance because as soon as I was offstage I could barely walk.” . . .

A feature by Ivan Ilić

I’ve come to the conclusion that the closer you get to big cities, the more you realize that the intelligentsia there is rigid, jaded. Living in Paris or in New York is like having a passport for stupidity. New York is no different than Paris; New York has its own pride. The people are from New York, they are New York, which they would like to believe can’t be bad. I just came from Great Britain, I spent three weeks there. I left from Scotland. Their audiences are informed; they knew my music. Then, I went down, down, closer and closer to London. Cambridge? Stupid! That’s why it’s best to stay away from the big cities; too many things, too many stupid things …

A feature by George Grella

Why Ostrava? In a way, because it was there. Along with the resources and the facilities—including several important, excellent new ones that are integral to the city's physical renewal—Ostrava is a place that, in Kotik's phrase, leaves you alone. Still substantially blue collar in look, feel, and social quality, there is no pressure to be hip, to be seen, to do any particular thing, or anything at all in particular. Despite the occasionally irritating air quality (there is still a working steel plant within the city limits), the city is comfortable to be in and to get around, it is spacious and green, with a solid public transportation system. There is not much to do except experience the music, which is the whole point. [...] But, why in Ostrava? Or rather, why do only the professionals and aficionados seem to know about what happens in Ostrava? Why can’t one read about the festival and the city in newspapers and general interest publications? With no particular bourgeois charm, with no particular material culture, with nothing particularly to do or see, rich people don’t go to Ostrava, so publications written in hopes that rich people will read them don’t cover Ostrava. The festival is about nothing but the music.

A feature by Ivan Ilic

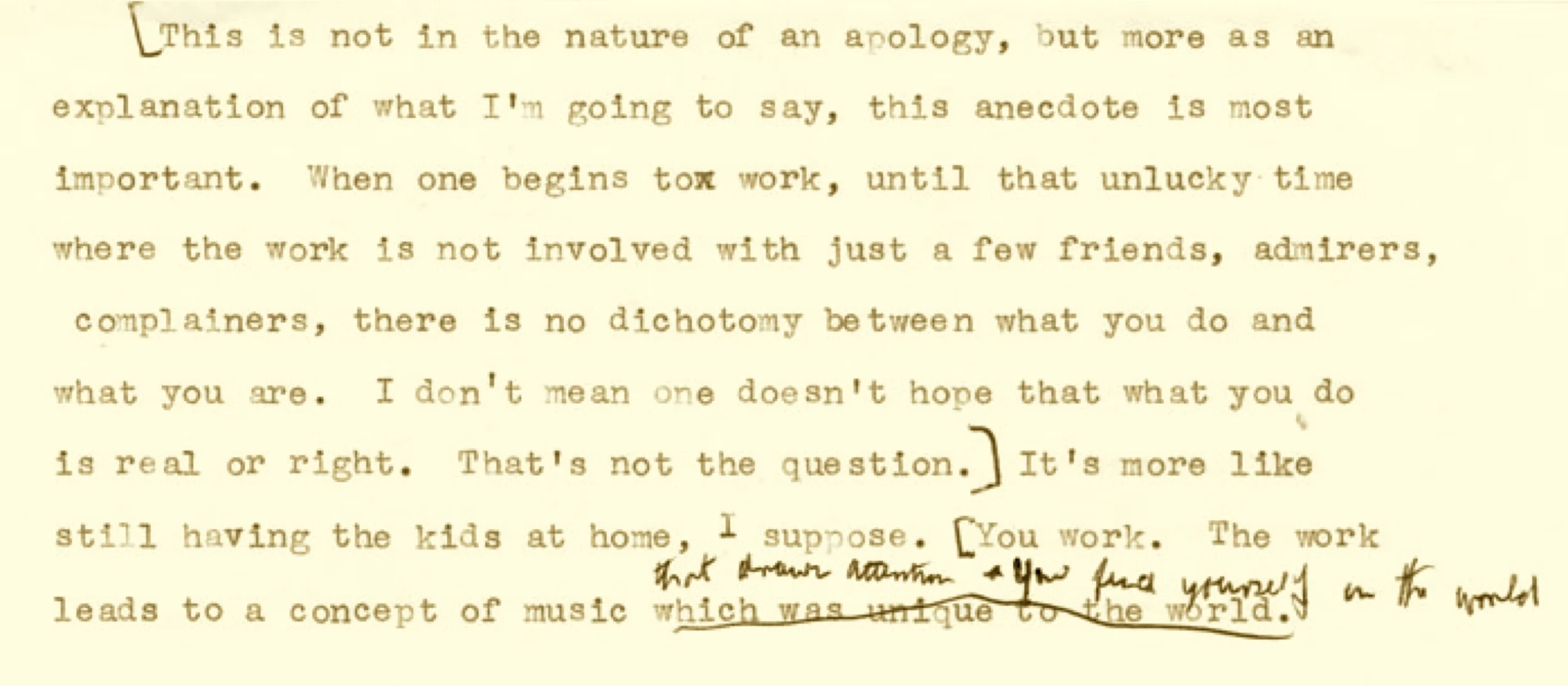

. . . The challenge for inexperienced listeners is that they can be so baffled by what they hear in the first few minutes of a piece by Feldman, that they may give up well before their ears adapt. To make matters worse, many listeners are loath to admit that they don’t “get it,” for fear of revealing a lack of musical expertise. Even though I have listened to many of Feldman’s works multiple times, and I regularly perform his piano music, I still need time to adjust too. I wonder: would it be possible to describe this adjustment, so that listeners know what to expect?...

Naja Marie Aidt’s poetry collection, Everything shimmers, is a prismatic and lyrical reflection on the relation between home and abroad, familiar and strange, including the strangeness of the familiar. The poems are about separation both as loss and liberation, exile both as grief and as blessing. They are about individual, family and colonial history, about colonizing or being rejected by foreign land . . .

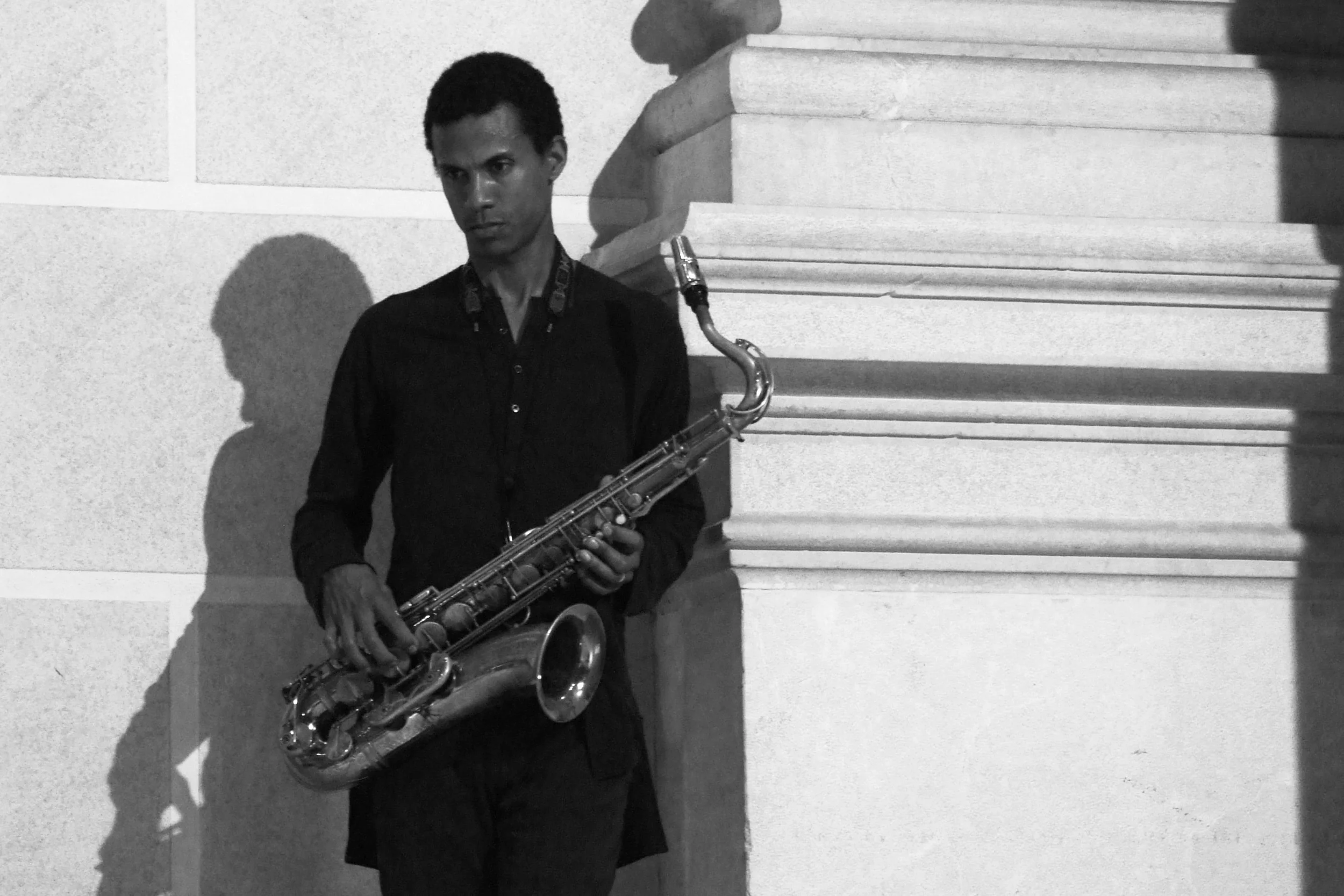

A feature by Kevin Sun

“He’s really unafraid to fail,” Ethan Iverson says. “Career shit, making the tune work—none of that matters; he just sees it as an epic cycle, and that’s why he’s Mark Turner. That’s why he gets to these great heights, because he has this other kind of warrior in him for whom failure is just another pleasant way to pass the time, you know?” Saxophone playing, just like anything else, has its fads, but Turner seems stylistically to have planted his feet firmly and pointing slightly inward since he moved to New York. As Turner himself points out, deciding what to practice is not just a day-to-day affair, but part of a lifelong commitment toward realizing an artistic self. “A lot of that in particular is just gradually clarifying your aesthetic and trying to figure out what you need to do to reach that aesthetic,” he says. “Otherwise, you can be practicing for millennia! I mean, you can practice one or two things for hours and hours and hours, twenty-four hours a day until you die. You have to decide on something.”

A feature by Kevin Sun

“Mark’s very lyrical, and that’s one of the things that moves me. A lot of students now can get around their instruments, but I don’t hear the lyricism. Now, you think about something like if I had to replace Mark,” says Billy Hart. “Of course, I had to deal with some possibilities, but there was nobody I could say, ‘Okay’ [snaps fingers]. Nobody. So then, for the first time, I had to think about it like when Miles had to replace Coltrane.”

A feature by Emily Cooke

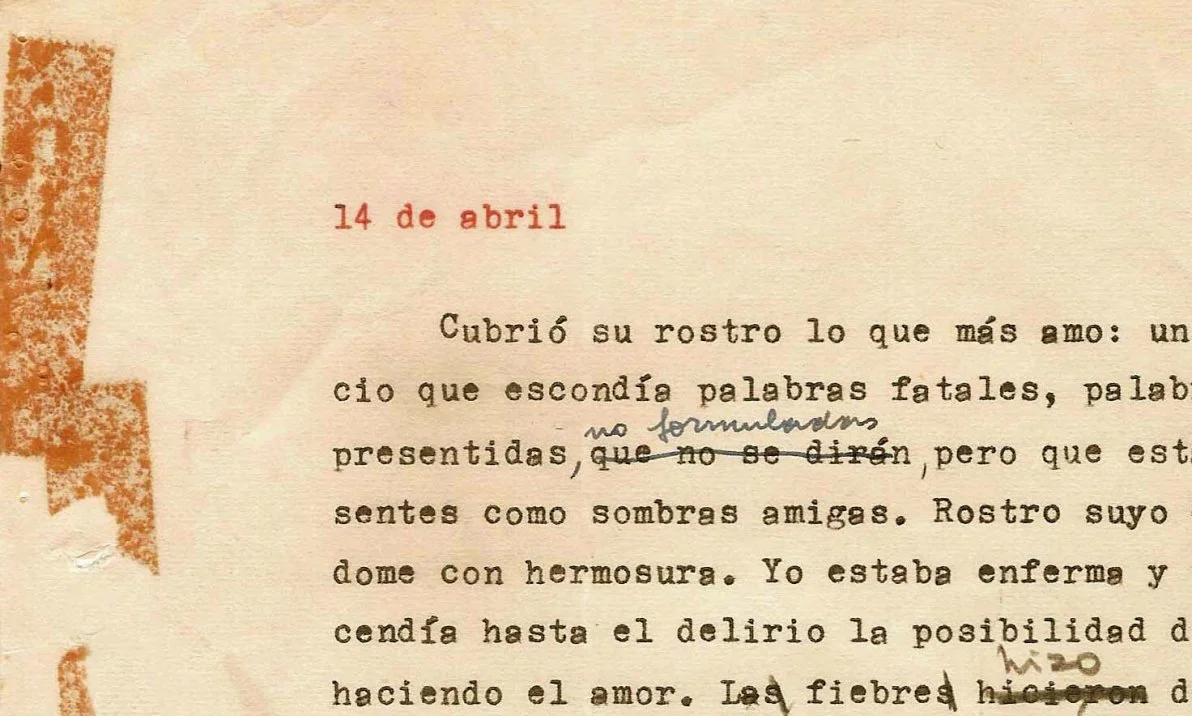

Alejandra Pizarnik's obsession with the form of her life—how it went, how it should go—is especially visible in her letters to her psychoanalyst, León Ostrov, a selection of which appears below. Pizarnik began seeing Ostrov in 1954, when she was eighteen. The analysis, which lasted barely more than a year, initiated a friendship that remained analytically alive long after it stopped being formally therapeutic. The conversation was not confined to Pizarnik’s “problems and melancholies,” as Ostrov would understatedly refer to the often debilitating mental illness of his former patient. Pizarnik and Ostrov shared their minor doings, riffed on books, discussed Pizarnik’s writing and career. Pizarnik visited Ostrov’s house and grew close with his family. Ostrov’s daughter, Andrea, remembers Pizarnik arriving at an elegant dinner party in a “furiously” red sweatshirt and pants. In 1960, when Pizarnik moved to Paris, she and Ostrov began regularly corresponding, and stayed in touch throughout the four years she lived abroad. The nineteen letters that survive this period (there are twenty-one in total; two date from earlier) showcase the young poet’s wit and spirit even as they reveal her anxieties. Pizarnik complains about her parents, insults her boss, mocks the Parisian literary elite (she’s appalled by Simone de Beauvoir’s screeching voice), wonders whether a poet should live artistically or like a “clerk,” and fantasizes about her artistic future. “I’m numbering the letters for our future biographers,” reads one postscript . . .

A feature by Dan Bilawsky

“There’s the famous story of somebody asking Michelangelo how he created the statue of David, and he said, ‘Well, I took a hunk of marble and chipped away everything that wasn’t David.’ I love that, because, to me, as a musician, I try so hard to get things right, but no matter how hard I practice, there are just some things that I can’t get. And I’ve come to understand that those things that I just can’t get, no matter how hard I try, are the marble that’s supposed to remain. If we all could do everything, we’d all sound the same. But because we all have strengths—and just important, weaknesses—there’s really a differentiation and a beauty of variety. Not only are you not expected to get it all right, but the stuff that you don’t get right helps to inform your musical personality or who you are. It’s helpful for me to talk about because I need to be constantly reminded [about it], because I can tend to really beat myself up about the stuff I don’t get right.”

A feature by Matthew Spellberg

Opera is an art form as hopelessly stylized as Noh or Kathakali. In their splendidly deadpan history of opera, Roger Parker and Carolyn Abbate put it like this: “Opera is in a basic sense not realistic—operatic characters go about their business singing rather than speaking.” Elsewhere, they elaborate only slightly: “That’s it. That’s opera. Just a lot of people in costumes falling in love and dying.” But opera, though structured like Bartók’s definition of folk culture, also participates fully in Western high art’s commitment to novelty, revolution, and innovation. And herein lies a problem, a second paradox. How do you make legible an art form that is at once stylized, and yet is always revising the code that translates the stylized into the everyday? Imagine a religion which every week changed most of the gestures and much of the language of its ceremony, but still expected the audience to follow it, to understand it...

Over the course of a five-decade career as one of the epoch’s outstanding musical artists, violinist Gidon Kremer has repeatedly tied his creative work to the tumultuous mast of current events. His service to the classical tradition and his tireless search for vital new compositional voices both dovetail with his consideration for what goes beyond music—the tragic events of our time, global hotspots, and individuals who have brought disquiet to millions. Kremer’s recent activism has been increasingly focused on one of his several homelands, Russia—the Russia incarnated in his “My Russia” and “Russia: Faces and Masks” projects as well as in concerts dedicated to Anna Politkovskaya and Mikhail Khodorkovsky. The following text is based on an interview conducted with Gidon Kremer for Colta.ru in November 2014. We spoke in Kiev, just before the debut of his project “Dedication to the Ukrainian People” . . .

Editing Blue Light in the Sky was one of my most rewarding experiences while working at New Directions, and I was really thrilled to receive an email from Can Xue recently saying she thinks it is one of her best works ever published. The biggest challenge for me in editing the translation was latching on to the style and hearing the voice. I might be wrong, but I think Can Xue emphasizes mood and story over highly stylized prose. Her voice is deliberately flat. Western literature draws on sources with which we’re all familiar: the Bible, Shakespeare, Homer, Dante. Can Xue’s biggest influences are writers like Kafka, Dante, Goethe, and Calvino, though I’ve read arguments elsewhere that her writing is rooted in emotion and landscape. I believe this is true. Her writing always conveys the constant threat of chaos lurking beneath. That said, the challenge of my job as editor was to see the arc in each story and make sure the sentences were correct, that the paragraphs flowed, and that the arc emerged clearly in each of the stories. As I said before, Can Xue’s stories are to me like modern abstract paintings, demanding the reader’s engagement in that particular way . . .

A feature by Paul Grimstad

The interesting thing about a game is that it has rules, and in the game of music the stricter the rules, the freer the composer, no matter whether it is an ABABCBB song structure or the most diabolic contortions of serialism. This is, I take it, one way to understand what is meant by “Apollonian”: Apollo, god of rules, order, measure. Stravinsky, committed anti-Wagnerian, exacerbates a distinction made by that most famous (albeit belated) anti-Wagnerian, Nietzsche, who thought the great distinction of Greek theatre—tempering the truth of Dionysian chaos with just the right dose of Apollonian order—went south after Socrates arrived on the scene and replaced the mystique of tragedy with pedantic Q&A. Stravinsky’s rule-driven musical discoveries are importantly different from serialism, the latter of which takes Wagnerian chromaticism to extremes of tonal egalitarianism. Pandiatonicism is differently freeing: it levels the playing field so that any kind of chord can show up at any point, but it doesn’t liberate tonality so radically that the ear becomes unmoored. Stravinsky remained an instinctive composer, he never lost trust in his ear...

A feature by Jennifer Croft

When away from Buenos Aires, I miss its sounds: the shrieks and yelps of kids on playgrounds, squawks and car horns, carts with giant wheels that scrape against the cobblestones, shouts, yips, chirps, steps. The dazzling, dizzying southern sun. The boisterous vegetation in the city’s parks—the gnarled roots of hundred-year-old rubber trees; the palo borracho with its creamy pink flowers and its spike-lined trunk . . . This constellation of incongruous and overwhelming forces is depicted differently over the course of Argentina’s rich artistic and literary tradition. An especially arresting perspective is taken by the poet Alejandra Pizarnik (1936-1972), whose mature works, published and unpublished, are being nimbly translated into English by Yvette Siegert in a beautiful volume entitled Extracting the Stone of Madness: Poems 1962-1972. In many of these poems we find ourselves cloistered against the frenzy of the outside world . . .