Review by Patrick Nathan

What drew me to Indigo, the newly-translated novel from Austrian wunderkind Clemens J. Setz, was its premise. Setz imagines an alternate dawn to the twenty-first century wherein a new medical condition is discovered: a congenital disorder that causes—in all those within ten yards of the afflicted—intense vertigo, nausea, and headaches. This condition, affecting a small minority of children all over the globe, tends to fade during late adolescence. The not-quite-PC term is Indigo children, coined from a misunderstood and far-from-scientific “study” involving a mystic, the imagined auras of personality types, and a blindfold testThese children, however mistakenly named, are from then on sought out at infancy, a parent’s every headache under suspicion, every sigh of fatigue analyzed for its cause. Since no one is able to withstand contact for more than a few minutes before vomiting or doubling over in pain, Indigo children are—in a depressingly familiar scenario—gathered up and confined to special schools where, scientists say, they’ll be “better off.” The absurd, deadpan history of Indigo sickness is typical of Setz’s novel, where arbitrary circumstances and emotional impulses have catastrophic effects on human lives . . .

Review by C.D. Rose

It is literature that can perform that vital act of remembering: it is the nature of words, after all, to hold memory. The Temple of Iconoclasts is a vivifying corrective to our all-too-human tendency to forget. It gives names and faces and lives to those who had been unnamed. It restores a reputation to those who have been (perhaps, in some cases, justly) forgotten. The book contains thirty-five brief accounts of the lives of men who have, in some way or another, attempted to challenge the orthodoxies of received belief systems, be they scientific, theological, geographical, cosmological, theatrical, literary, bibliographical, or critical . . .

Review by Keenan McCracken

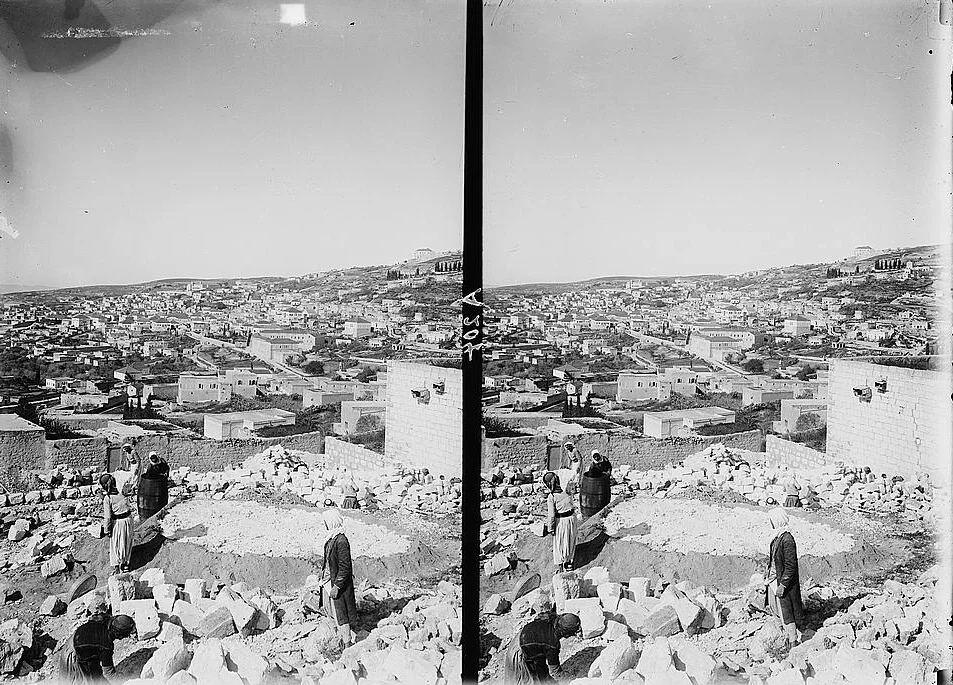

Occasionally, there are writers we encounter who so pointedly articulate the truth of a particular condition or facet of human existence that they nearly colonize it—Proust and memory, Faulkner and the American South, McCarthy and the nature of evil—writers whose identities become so inextricably linked to that thing that formulating a personal understanding of the subject wholly independent of their writing seems impossible. In the case of Elias Khoury, it is the Palestinian history of exile and war in the twentieth century. For “death,” according to Khoury, “liberates the memory,” and it is by drawing on his firsthand experiences of murder and dislocation that he has created a body of work, including his masterpiece Gate of the Sun, that will very likely be read and remembered decades from now.

Review by Jordan Anderson

This paradox of memory and denial poses a unique problem to artists. They often explore regions of empathy avoided by other sectors of culture, and so they venture furthest into the capacity for empathy with those “forgotten” by society. As such, those artists may have the most profound influence on the moral understanding of our age. By this measure, Naja Marie Aidt undeniably approaches the realm of great artists. Her work, as demonstrated in the recent publication of her short-story collection Baboon, shows the author to be concerned primarily with the use of empathy in its most unromantic form: with people as they are rather than as we would wish them to be . . .

Review by Dustin Kurtz

Early in Paradise & Elsewhere, her latest short-story collection, Kathy Page places readers in an Edenic oasis of plenitude, communal and iridescent, populated by immortal women—a bubble about to be ruptured by a stumbling heat-stricken outsider. The women of this paradise discuss the intruder—a useful gloss of that story and, indeed, the entire book. In these stories Page gives readers a literature of elsewhere, but one in which difference—or, as above, “differentness”—is not a truth laid bare. Oddity, the fantastic, the cruelty that accompanies them, is not the point. Instead it serves only to highlight a longing, across stories and characters, for a kind of transcendent understanding or (and they amount to the same thing) an escape . . .

Review by Jeffrey Zuckerman

“Sometimes words say what they want to say,” the unnamed narrator of David Albahari’s Globetrotter tells himself near the book’s end, “and there is nothing we can do about it.” Instead of “words,” he almost ought to have said “people.” But it would never occur to him to do so: his own loquacity, in fact, is the driving force of Albahari’s novel. The single, unbroken paragraph that flows through Globetrotter’s two hundred pages is narrated entirely in this solitary and self-absorbed voice, working through its obsessions and curiosities with a wide-ranging eloquence . . .

Review by Madeleine LaRue

The Rwandan author Scholastique Mukasonga’s Our Lady of the Nile works as both a collective coming-of-age story and a prelude to genocide. Through a series of vignettes focusing on individual characters or events, Our Lady of the Nile gradually exposes the fault lines that will, in the end, tear both the eponymous lycée and the country apart. Within these fault lines is a sort of competition, a contest for survival between different ways of being—European and African, Hutu and Tutsi. The competition is deadly for most, but Mukasonga does not strand us in tragedy. She works hard to trace out an authentic, if fragile, means of survival for her protagonists, refusing to succumb, in the end, to total despair . . .

Review by Craig Epplin

“Books for when you’re desperate”: this phrase, drawn from The Savage Detectives—along with the fact that it is identified with the young Roberto Bolaño and his Mexico City literary comrades—underscores the ambition, central to much of the Chilean author’s fiction, of finding ways to make life and literature unfold together. In desperation's grip, literature becomes an urgent, life-and-death matter, the place of everyday ecstasies and miseries. A Little Lumpen Novelita—the last of his novels that Bolaño lived to see published, now translated by Natasha Wimmer—has, at least on the surface, little to say about literature but lots to say about desperation . . .

Review by Timothy Aubry

The Irish novelist Eimear McBride’s debut A Girl is a Half-formed Thing has experienced surprising success given the challenges presented to its readers. The novel’s nameless narrator describes a life emotionally terrorized by two separate traumatic ordeals, and her experiences are reported in a fragmented prose style brashly defiant of practically all grammatical and syntactical conventions. But in many ways, McBride’s novel is less unconventional than it seems . . .

Review by Caroline Bleeke

Elena Ferrante’s narrators, women who employ a viscerally candid first person, speak to us about their childhoods, their morbid fear of becoming their mothers, their daily trials and anxieties, their desire and disgust. They hold nothing back in their interrogations of motherhood, daughterhood, marriage, sex, love, success, and contentment. And Ferrante’s Neapolitan novels—My Brilliant Friend, The Story of a New Name, and now Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay—expand outward. They capture not only the intimate musings of a narrator who grows up before our eyes but a panorama of postwar Italy, intricately peopled with a vital supporting cast, including the indelible Lila. Elena’s torturous, lifelong friendship with Lila drives the entire sequence: “her shadow goaded me, depressed me, filled me with pride, deflated me, giving me no rest.” Their mercurial dynamic fuels their lives, which in turn fuel Elena’s stories, the pages we are reading . . .

Review by Meghan Houser

Dispatched from the divide between life and art, Valeria Luiselli’s writing is deeply, inventively concerned with not only defining identity but freeing it from the constraints of definition. Her metaphors are spatial—cities and maps, architecture and navigation—and while she explores how her characters inhabit their physical surroundings, the architecture she’s ultimately concerned with is writing itself, that most elastic human construct. How do we inhabit the invented spaces of language, which, to Luiselli at least, occupy at least as much of our consciousness as the world in which we move? Layering artifice and accident, what she creates are houses of ghosts, but not Allende’s; invisible cities, but not Calvino’s; visceral realism, but not Bolaño’s . . .

Review by Ariel Starling

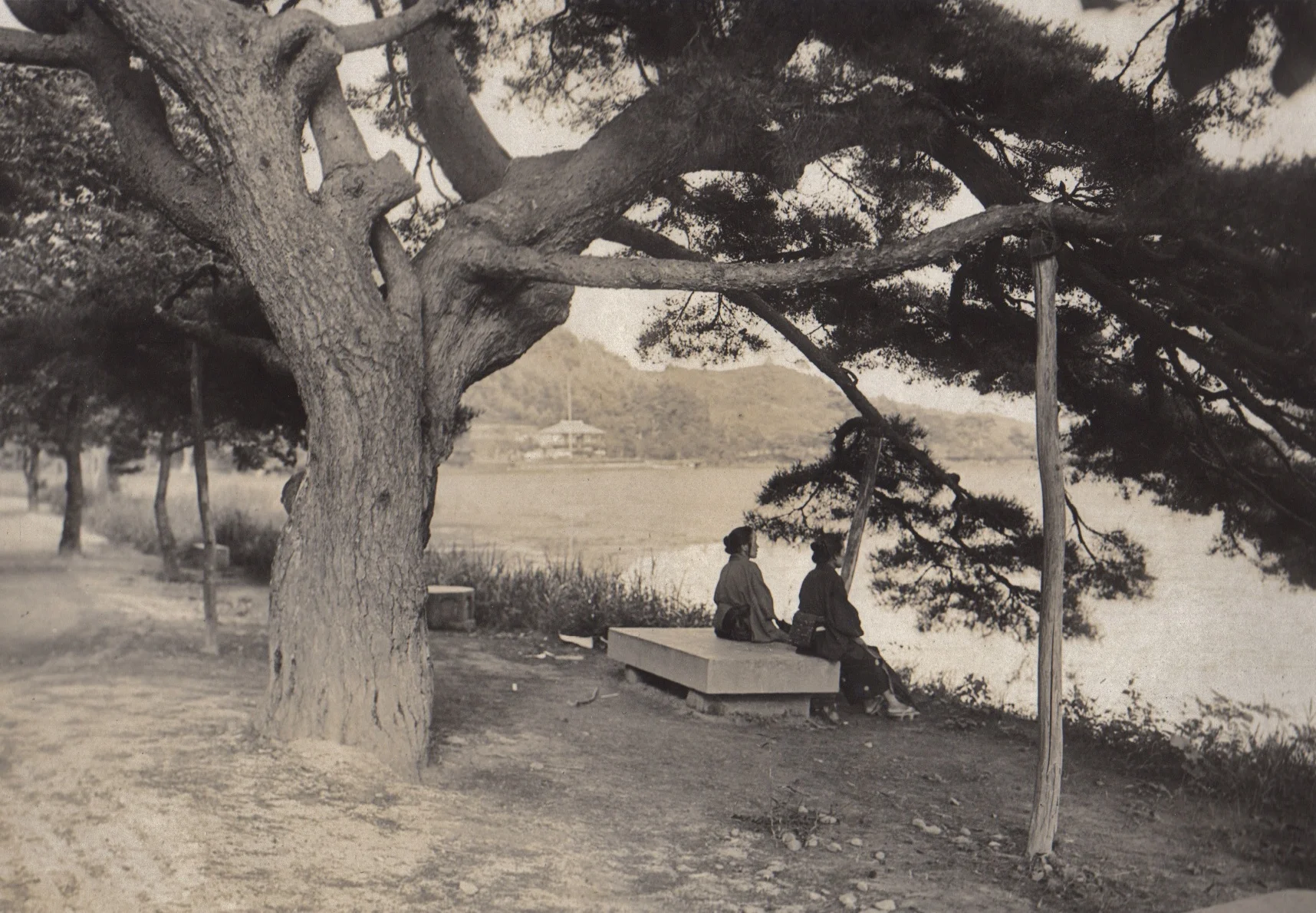

Yasushi Inoue did not make his debut in literature until 1949 at the age of forty-two. He did so with the two short novels Bullfight and The Hunting Gun; the former won him the prestigious Akutagawa Prize—the Japanese equivalent of the Pulitzer—and he went on to write over fifty novels and win every major Japanese literary prize. It seems safe to say that Inoue was worth the wait. Despite occupying the upper echelons of postwar writers in Japan, he has not yet achieved the western readership of his Nobel-Prize-winning contemporaries Yasunari Kawabata and Yukio Mishima. The matter may best be chalked up to the fact that literary renown, particularly for literature in translation, is a strange beast. Whatever the cause, it has nothing to do with Inoue's caliber as a writer . . .

Review by Will Heyward

Gerald Murnane's A Million Windows is organized into a series of fragments, many of which describe an image or a succession of connected images. Interspersed with these images are discussions of different aspects of the craft of writing fiction, with the narrator complaining about how a particular book that he once admired has come to disappoint him. These images, memories, and discussions never progress, at least not in the way a story does; instead they intersect obliquely, carrying traces and hints of desire, longing, regret, apprehension, and misunderstanding whose painfulness or meaning is not always immediately clear . . .

Review by Tynan Kogane

Jean-Patrick Manchette's The Mad and the Bad is an entirely profane nightmare, which only flirts with moral or ideological messages, throwing them out in offhand ways, so as not to distract too much from the thrill of the ride. And what a ride! The day after beginning her new job as a nursemaid, both Julie and Peter are kidnapped and flung into an elaborate plot, which begins to spiral out of control as the unlikely pair are pursued across France by a sickly hired assassin named Thompson and a couple of his cronies. Thompson is an exemplary hard-boiled character, who embodies many of the genre’s ideals, but he’s tired and washed up, as though these ideals have decayed inside of him, hollowing him into a saggy balloon-like caricature of the typical hard-boiled hero . . .

Review by Anne K. Yoder

What became of this person, this life? How can he be here one minute, and then gone forever the next? Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi’s first novel, Fra Keeler, begins with this endpoint in mind. Fra Keeler has died, and the unnamed narrator moves into his house to become the self-appointed investigator of Fra Keeler’s death . . .

Review by Emmanuel Iduma

Ingrid Winterbach's The Elusive Moth is an exploration of a strange kind: each inch covered is more or less a marathon. Winterbach’s writing reads as a deliberately paced uncovering of broken things and lives within a ruptured space . . .

Review by Andrew Marzoni

For better or worse, the energy and desire for political change—radical political change—is more often than not left in the hands of those without the wisdom, experience, and understanding to effect it: the young. This Catch-22 of revolutionary fervor is a phenomenon that Czech writer Jáchym Topol understands well. One of the most prominent journalistic voices of 1989’s Velvet Revolution, Topol is now a widely respected novelist, heir to a literary culture whose giants—Václav Havel, Milan Kundera––are as well known for their political activity as for their creative output. Unsurprising for a novelist brought up within the Eastern Bloc, Topol’s novels are primarily concerned with history, and in Nightwork—his fourth novel, first published in 2001 but just recently made available in English––he turns to the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, commonly referred to as Prague Spring . . .

Review by Mieke Chew

“The most important writer of the decade” were the words used to describe Hermann Ungar in 1927. This was no small praise for a contemporary of Döblin, Kafka, and Musil. But less than a century later, Ungar has been all but forgotten. The Second World War has played no small role here. Ungar's books, too, were controversial. The critics couldn’t stomach Ungar’s indecent scenarios. Rather than pan the book, they ignored it completely. Ungar died young and found new enemies in death. Max Brod and Willy Haas were not men to cross in the 1930s world of letters; it seems that they worked to make this singular writer forgotten. It would appear that they succeeded. Ungar was as virtually unknown in his lifetime as he is today. Somehow his books remain in print and English translations are readily available. This is our great fortune; nearly a century later, Ungar’s beautiful, clear prose, and shocking, comic narratives remain every bit as vital and original . . .

Review by Patrick Nathan

The extraordinary popularity of Gabriel García Márquez and Roberto Bolaño has spawned translations of other Spanish-language writers, whose books, it turns out, aren’t so easy to dismiss as ornaments of “the other.” Instead they position themselves, sometimes aggressively, in the real world. In Mairal’s The Missing Year of Juan Salvatierra—as in many other novels of this new generation—art has replaced magic as the immense, central presence. It’s become the thing we can’t ignore . . .

Review by David Winters

Joseph Cornell’s air of mystery has attracted many literary admirers, and Gabriel Josipovici appears well-acquainted with these precursors. It is partly thanks to their inspiration that he has now created his own Cornellian novel, named after a box filled with stars and scraps of paper: Hotel Andromeda. Josipovici is a writer who prizes “lightness,” and his airborne prose never tethers or traps Cornell’s art; never encases it in the amber of comprehension. Rather, his narrative subtly circles around its subject, tracing the outlines of a shape which remains “untouchable, unknowable” . . .