Review by Jennifer Kurdyla

There’s some irony in the way that the largely forgotten French-speaking Swiss writer Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz so wholly and purely embraces pathetic fallacy in his work. Two of his most recently rediscovered publications, the novel Beauty on Earth and the book-length prose poem Riversong of the Rhone, in new translations from Onesuch Press by Michelle Bailat-Jones and Patti Marxsen, respectively, show how Ramuz employs this fluid experimentation with language that was emerging during his day to communicate a oneness between man and his environment. He straddles a line between the old and new on the level of content and form, and in both he strives to convey the eternal quality of existence and, in particular, beauty . . .

Review by Adriana X. Jacobs

The soldiers in S. Yizhar's Khirbet Khizeh remain in a state of waiting that slowly ruins them, as it does the village, all the villages, that they have conquered. This ruin is in the book’s very title, an amalgamation of the Arabic khirbet (“a ruin of”) and the Hebraized Khizah (in Arabic it would be pronounced Khizeh, which the English translation reinstates). The soldiers have become the walking dead, covered in fleas like the dog carcasses rotting beside them, but the text also shows signs of ruin and breakdown in its meandering plot (if this word even applies), sharp transitions, puzzling syntax. S. Yizhar’s prose requires a reader to reassemble sentence order, another way that the distance between reader and speaker collapses, but the stream-of-conscious effects that he employs also lull a reader into a kind of trance and then, suddenly, as for the soldiers, a sudden movement brings the reader back into the text and scrambling to figure out how they got there. In these moments, rereading feels very much synonymous with retracing and rewriting . . .

Review by K. Thomas Kahn

How does one begin to write the history of a woman whose narrative has been submerged, both beneath that of her husband and beneath time itself? How does one set about reconstructing a life from scant fragments, oral histories that carry with them their own subjective—and often biased—versions of the “truth”? Is it even possible to excavate a female artist from obscurity when most artists often inadvertently and unwittingly take part in their own self-erasure? These are some of the questions Nathalie Léger considers in Supplement à la vie de Barbara Loden, her widely-acclaimed and prix-winning 2012 book. Freshly translated by Natasha Lehrer and Cécile Menon as Suite for Barbara Loden, Léger’s Suite raises resonant points about the nature of influence upon artistic creation, the thin and often tenuous line between fiction and reality, and the impossibility of building biographical pictures without a visible (and wholly participant) narrative voice balancing truths and half-truths, all the while applying the lessons learned from sifting through buried archival materials to one’s own experience—what Léger describes aptly as “my dream of a fictional archive” . . .

Review by Ryu Spaeth

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated from Korean into English by Deborah Smith, is concerned with the seismic repercussions that follow a seemingly innocuous event: Yeong-Hye’s sudden, mysterious decision to stop eating meat. (Her only explanation: “I had a dream.”) However, if vegetarianism in the West has become as ubiquitous as the Happy Meal, it is a rarity in a country where Spam comes in gaudy gift boxes, nose-to-tail is not a culinary trend but an age-old tradition, and few people outside Buddhist monasteries are concerned with the ethical dilemmas of eating animals. Yeong-Hye, then, is a rebel, if a fairly passive one, and like all outsiders, her alienation serves as a commentary on the community from which she stands apart. But while The Vegetarian certainly relishes its attacks on contemporary Korean society, it is also much more than that, an examination of what happens to a woman who, like Kafka's hunger artist, tries to transcend her appetites—which is to say, the bounds of what it means to be human . . .

Review by Matt Mendez

The title, borrowed from a children’s piece of the same name by Mauricio Kagel, is a play on words: zählen corresponds to “counting,” erzählen “recounting” (in the sense of an account or tale), and when in proximity the two summon up some of the affinities between reiteration and narrativity. Certainly, it comes as no surprise that this tissue of associations resonates with the Germanophile Abrahamsen, whose credo is “music is already music,” that “what one hears is pictures—basically, music is already there.” This is, after all, just another way of saying that writing and rewriting are not so easy to disentangle, that even the most schematic reshuffling of old work brings to bear a mediating sensibility, and that the creation of purely “original” music entails a sort of bricolage in the opposite direction . . .

Review by Craig Epplin

Intimate memories, our bodily relationships with machines, the generational succession of technology, the lure of non-writing, and rhythm as a measure of experience—these concerns wind their way through many of the stories in Alejandro Zambra's My Documents. They are compactly present from the beginning, nested in the opening pages of a memoir-like story titled “My Documents,” is inhabiting the first pages of a collection of the same name. This recursive structure is no accident. Rather, it mimics the nested pattern typical of personal computer files, which can be copied and moved around, which can have shortcuts of the same name, which can be printed out and put together as a book. This is precisely the effect that My Documents seemingly wants to cause: the impression that each individual story forms part of a loosely-conceived totality, held together by proximity as much as by thematic concerns or authorial obsessions. These are just notes, some of the stories seem to say, while others feel more polished. Journal entries, fragments, lists, bad jokes, and regular short stories—Zambra alludes to a number of different genres of writing, yet My Documents still feels cohesively unified . . .

Review by Rodge Glass

The sheer weight of Alasdair Gray’s output in the last decade or so is enough to challenge the attention (and the wallet) of his most ardent supporters. How do you keep up? He switches publishers for almost every publication. He supports the small and the local ones where he can, meaning some of his books go virtually unnoticedGray controls every aspect of each of his projects, the textual and the visual, right down the margins and even the typeface, one of which he has invented himself. It’s overwhelming, sometimes confusing, and—if you pick the wrong book—it can be disappointing. With a writer of this kind, where on earth does someone new to Gray's oeuvre even start? Oddly enough, this retrospective collection of bits and literary bobs, Of Me & Others, is the perfect place. The author suggests it might have been titled A Life in Prose. That would have been appropriate.

Review by Daniela Cascella

Records excite and disturb. Records frustrate and exhilarate. Records call for repetition. Records ruin the landscape: or such is the claim, famously made by John Cage, that gives the title to David Grubbs’s new book. Many musicians operating in 1960s American and European avant-garde and experimental circles shunned such a crucial and controversial element in our perception of music as recorded sound—most notably Cage and Derek Bailey, who stated that their music could only be experienced in full in ephemeral performance settings. And yet many of these musicians allowed their music to be recorded, as evidenced by contemporary releases as well as the numerous archival recordings that would appear decades later, first as CDs and then online. What are the implications of such aural revenants on music practice, on listening and understanding today? And how can the ephemerality of 1960s music performances be compared with another form of ephemerality, represented nowadays by the enormous quantity of audio recordings available online?

Review by Tyler Curtis

Perhaps this is the central concern for Daniel Galera in Blood-Drenched Beard, the economy of symbols, identity, and time. The face, an ever-fluid symbol, has typically been a referent for the subject behind it. For everyone but the protagonist, that particular symbol itself grows roots in one’s mind. But the protagonist’s prosopagnosia makes clear that personhood is just as fluid and tied to the currents of change in time as one’s aging skin. The order and tone of one’s face is commonly transformed into a bodily grammar for the language of the subject, and though it is left fleeting and (visually) unintelligible for our protagonist, he finds himself closer to a more essential unity of the word and the world, how the former in fact constitutes the latter . . .

Review by Tim Rutherford-Johnson

The Anatomy of Disaster (Monadologie IX), written in 2010 by Austrian composer Bernhard Lang, begins like a broken machine. Not one of György Ligeti’s delicately collapsing clockworks or the softly glitching CDs of German electronica group Oval, but a fast, heavy, gunning engine, flailing wildly and dangerously. But not fatally, because the music quickly takes on a chaotic shape of its own. Fragments turn into components. A hiccuping, short–long rhythm metamorphoses into a motif. The thick texture turns out to be comprised of thinner, overlapping layers. And amongst all the dissonances there are sudden glimpses, baffling at first, of the harmonies of a much older language . . .

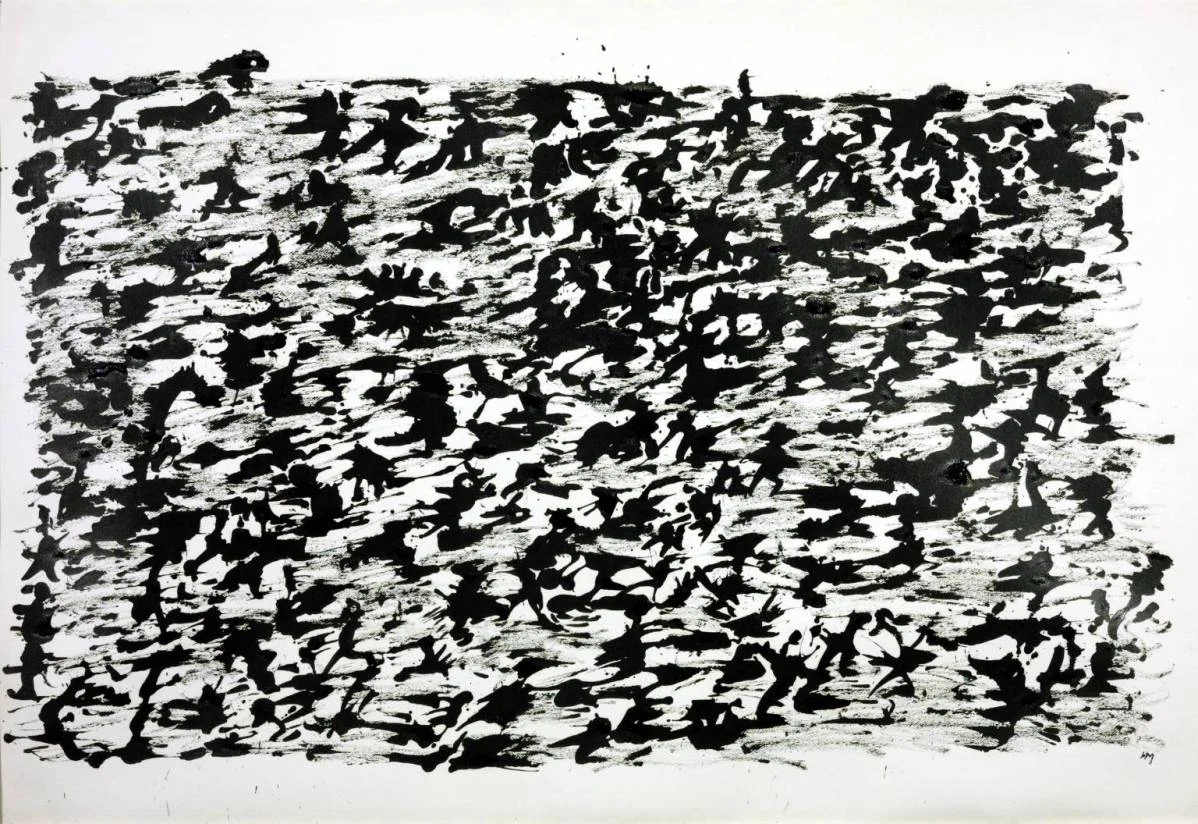

Review by Caite Dolan-Leach

Henri Michaux arrived in Paris in 1924, the same year that André Breton published the First Surrealist Manifesto. Michaux is often mischaracterized as a “Surrealist”; he dabbled a little in the inescapable clan of writers and artists, and certainly shares their concerns about the failures of language and divisions of the self. In the newly translated Thousand Times Broken, a slender volume of poetry, prose and black and white images (exquisitely translated into captivating, strange English by the poet Gillian Conoley) Michaux continues to explore his lifelong fascination and tormented investigation of whether the self can be accessed, whether words or drawings best capture meaning, and whether communication is possible at all. As an artist and writer, he is radically divided, torn and trying to unite all of his conflicting convictions and disparate aesthetic projects . . .

Review by Hilary Plum

It was not until reading Amjad Nasser’s exceptional novel Land of No Rain that I considered just how close the phrase “second person” is to “the double.” In second-person narration, the “you” threaded through the syntax of a novel demands that the reader occupy a life she must pretend is her own. Reading works written in the second person often feels like overhearing someone’s conversation with, or instructions to, herself. In the case of this novel, that premise has been, as it were, doubled: the “you” addressed throughout has, or is, a double. In Nasser’s intricate, mesmerizing prose, we readers become someone we’ve never been, while our protagonist confronts the self he no longer is . . .

Review by Paul Kilbey

What are we laughing at, then? The chiselled precision of Wilde’s play, or the roughly scissored wildness of Barry’s opera? Despite the drastically divergent aesthetics, the answer is both: Barry is canny enough never to drown out the original—rather, the opera provides a remarkably effective means of experiencing the play afresh, both justifying The Importance of Being Earnest's canonical status and reinventing it for a contemporary audience. It’s this bizarre, perhaps unexpected sensitivity that is the primary proof that Barry is not in fact a precocious though impish seven-year-old, but rather a highly talented composer . . .

Review by Walter Gordon

The way in which the novel is written—in conjunction with a few genuine historical similarities—makes it easy to read The King as a sort of playful, metaphorical examination of the Iranian revolution. In this mode, historical fiction becomes a kind of activism, writing allows us to resist through the illumination of the horrors hidden by the triplicate shadows of power, progress, and propaganda, which existed then and exist now . . .

Review by Madison Heying

In the wake of the Napster controversy, literary scholar and composer Andrew Durkin began formulating the conceptual seeds for his Decomposition: A Music Manifesto. He observed that reproducing technology—from the player piano and the gramophone to the Internet and MP3s—had been changing how people listened to music. He had the “suspicion that something important has been ignored or forgotten . . . , obscured by our myths about music.” Myths are the values and beliefs attributed to music and its creators that paint them in a superhuman light. Decomposition was the result of Durkin’s thinking about the ways in which the myths of authorship and authenticity are inexorably shaped by cultural, psychological, economic, and technological factors. If these factors are inescapable, Durkin says, then listeners can—or even must—harness these factors in order to empower themselves to act as creative participants in their musical experiences . . .

Review by Tynan Kogane

Why is Benito Pérez Galdós considered a very important nineteenth-century novelist if no one reads him anymore? He is only rarely summoned from the purgatorial holding cell of dead and forgotten authors, and never definitively. His name doesn’t come up very often in conversation these days, or at least none of the conversations that I overhear. He doesn’t seem to have any literary apostles or outspoken fans, and no one gushes over his work, at least not in the same way that critics and readers occasionally gush over the work of the other European novelists of his generation. What is Galdós’s hook? How do you read (and think about) a so-called major writer whose literary reputation in the English-speaking world is either nonexistent, buried within academia, or the confusing punch line of a complicated joke?

Review by Alex McElroy

Andrés Neuman is unthreatened by borders. If writers are born in response to trauma, then Neuman, the writer, emerged when his family fled Argentina for Granada when he was fourteen. Now Neuman, not yet thirty-seven years old, has already published nearly twenty books, and at the center of his literary endeavors are the repercussions of loss and dislocation. Neuman has spent his career crossing boundaries both literary and geographical, and it feels appropriate that he would tell The American Reader that the move to Granada instilled him with "a sense of strangeness towards geography, towards the space in which you're telling a story, towards the origins of the characters" . . .

Review by Bwesigye bwa Mwesigire

Kintu, a historical novel by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, won the 2013 Kwani? Manuscript Prize. Kwani Trust launched Kintu in Kampala in June and even now, in December, the leading bookstore in the city can’t stock enough copies. The book is literally flying off the shelf. This is odd: most Ugandan bestsellers are also successful around the entire world, but Kintu is hard to come by outside East Africa. Makumbi says that she knew that her book would be hard to sell to Western publishers. “Europe is absent in the novel and publishers are not sure British readers would like it,” she told Aaron Bady of The New Inquiry. “I knew this when I wrote it. I was once told, back in 2004, when I was looking for an agent for my first novel, that the novel was too African. That publishers were looking for novels that straddle both worlds—the West and the Third World—like Brick Lane or The Icarus Girl but I went on to write Kintu anyway.”

Review by P.T. Smith

Limonov , the latest in Emmanuel Carrère's run of novelistic nonfiction, is a wonderful, weird journey. Translated by John Lambert, this biography of Eduard (Eddie) Limonov, a wild Russian, combines the excitement of a thriller with the deep moral questioning of a French philosopher. Its lengthy subtitle-"The Outrageous Adventures of the Radical Soviet Poet Who Became a Bum in New York, a Sensation in France, and a Political Antihero in Russia"-is simultaneously hyperbole and understatement. Limonov is an utterly fascinating figure: a violent, unstable bastard, he's also charming, loyal, and loving. People who enthusiastically agree with him one minute are appalled by his opinions the next. But he's "someone who didn't leave people in the lurch, who took care of them if they were sick or unhappy, even if he didn't have anything good to say about them." Minus the memory loss and the intoxication, his life resembles the Russian drinking binge zapoi . . .

Review by Jennifer Kurdyla

Being greeted by such a friendly face on the cover of The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories would seem nothing but inviting, but Tove Jansson may be counted among those artists who often arouse suspicion: artists who work in multi-hyphened mediums. Encountering such a writer-painter-cartoonist-lyricist gives people pause. Perhaps it’s due to an incredulity of how an individual could be a “master” of more than one thing—all that dabbling must diminish the quality of the work in any single format. Yet Jansson’s affable, trusting visage does not belie an oeuvre any less trustworthy. She’s a wholly suspicion-less, and wholly multi-talented, artist. Reading just one sentence from her published works for adults and children highlights how Jansson’s illimitable energy propelled her to create in so many genres . . .