Review by Joshua Daniel Edwin

Although i mean i dislike that fate that i was made to where is Sophie Seita’s English translation of Uljana Wolf’s German poetry, this simple binary does justice to neither side of what it describes. Both texts, the original and the translation, are inter-lingual. They rely on linguistic multiplicity: they work in it; they are made of it . . .

Review by Bruno George

Berit Ellingsen's Not Dark Yet is ultimately a Robinsonade, its Crusoe, Brandon, willingly isolated in a cabin in the woods. Even the novel’s first line expresses harkens back to Crusoe the world-traveler: “Sometimes, in Brandon Minamoto’s dreams, he found a globe or a map of the world with a continent he hadn’t seen before.” But unlike Crusoe, Brandon doesn’t save himself and his isolate world through deep-sea salvaging and strict accounting. Standing before his cabin for the very first time, Brandon has a yielding, melting, anonymous experience that sharply separates him from Defoe’s energetic and autonomous Crusoe: “He closed his eyes and there was no body, and no world either, only the simple, singular nothingness he recognized as himself” . . .

Review by Anna Zalokostas

“How long does a thought take to form?” asks a woman in Vertigo, a collection of linked stories by British writer and illustrator Joanna Walsh. “Years sometimes. But how long to think it? And once thought it’s impossible to go back. How long does it take to cross an hour?” Sometimes it takes hours to finish a sentence, a lifetime to find a city from which it becomes possible to begin. Time in Vertigo doesn’t so much slow down as it does short-circuit; the present moment is suspended, each instant expanded. Stories pass by like slow motion film; long stretches of thought are torqued by the white noise of the ordinary. This is a liminal space that eludes situation, an amplified present that expands the possibilities of genre . . .

Review by Jordan Anderson

In Marcus's assessment, “Last Kind Word Blues” represents of the degree to which America inadvertently tends to cut its own mythology from the cloth of a deeply oppressed underclass that shares little resemblance to the “respectable” status quo. Akin to the lost-by-history legend of blues musician Robert Johnson, who left behind as little historical trace as possible, Wiley and Thomas were obscure blues artists who created songs for Paramount Records, a label notorious, Marcus notes, for the poor quality of their recordings (the label was begun as a sideline by a furniture company to sell records for the gramophones they hawked to customers). It is in the near-total obscurity of Wiley and Thomas that Marcus finds a sort of counterpoint to America as it would like to see itself . . .

Review by Rosie Clarke

Critchley begins his Memory Theater with an arresting statement: “The fear of death slept for most of the day and then crept up late at night and grabbed me by the throat.” His relationship with mortality thus cemented, the tone is set for the novel’s remainder. The trigger for its particular investigation into death is Critchley’s discovery of a mysterious collection of papers belonging to his deceased friend, Michel, in which he finds an odd set of hand-drawn charts, resembling astrological maps. Michel’s own chart accurately predicts events in his own life occurring after its completion, including, troublingly, his death in a sanatorium in 2003, with Critchley concluding that, “Knowing his fate, he had simply lost the will to live.” Such composed reflection is rapidly dispelled upon discovery of a chart bearing Critchley's name, comprising intimate and private details of his and his family’s life, and, with alarming exactitude, the time, date, location, and cause of his death. Initially, this discovery inspires a quiet calm in Critchley . . .

Review by Jennifer Kurdyla

Catalonia, the home country of the revered mid-century writer Mercè Rodoreda, is a land of betweenness. Nestled in the crux of France and Spain, it is technically referred to as an “autonomous community” of the latter—in other words, depending on who you ask, perhaps its own country, perhaps not. As one of the most famous artists (alongside Salvador Dalí, who was also Catalan) to spring forth from this land of uncertain boundaries and identities, Rodoreda almost too perfectly represents this torn state of mind in her works of fiction, where characters and settings are constantly shifting between dreams and reality, apposite desires, nationalist claims, life and death. In her penultimate novel, originally written in 1980, War, So Much War, she demonstrates in phantasmagoric Technicolor brilliance the ways in which even such a cleft spirit can be a vessel for extreme beauty . . .

Review by Alex McElroy

Andrés Barba’s fiction is a zone of transformation, and in August, October and Rain Over Madrid, Barba’s first full-length works translated into English, the author attends to more understated manners of transformation: puberty, fatherhood, and grief. These transitions are not so much physical as emotional, and they signal a shift in Barba’s work, a move away from the gritty realms of prostitutes and orphans to the unspoken depravity of domestic life . . .

Review by Xenia Hanusiak

. . . It is only later, when you leave the room, that the weight of Mr. Gharani’s story drops and the orchestration of the recitative begins to unbalance your first perceptions. Mr. Gharani’s voice uneasily revealed that he was so badly abused he tried to commit suicide twice. An interrogator stubbed out a cigarette on his arm. He was kept in freezing conditions, sleep-deprived, and with alternating experiences of unpredictably blasted music and flashing strobe lights. The violin’s beautiful shudders, the potent guitar drones, and the flippancy of the American hoedown were the re-imaginings of this horrific incarceration. It was the soundscape of Mr. Gharani’s heart, of the existence he was forced to endure. In the clear hindsight of daylight, the experience is more sinister than I realized at the time. It was we who were being interrogated . . .

Review by Dustin Illingworth

At first glance, Ceridwen Dovey’s Only the Animals seems to slide easily into this literary tradition of creaturely appropriation. This collection of ten tales told by the souls of dead animals, finds Dovey writing in a semi-fabulist mode, though her thematic concerns—nothing less than what it means to be human—have expanded considerably from her debut effort. Each of the animals, having been caught up in a historical human conflict, tells the story of its own death. These vignettes are by turns heartbreaking and hilarious, and Dovey’s exceptional pacing ensures her readers remain engaged and enchanted throughout. No Disneyfied cautionary tales, however, are to be found herein. Dovey eschews sentimentality and easy moralizing, lending a sophistication to the proceedings that feels like a respect for the strangeness, and the ultimate unknowability, of wild consciousness. The eponymous animals are neither naïvely comic, nor possessed of the icy perfection and opacity of mythic beasts; rather, in their psychological richness and complexity of emotion they remind us nothing so much as ourselves—only sharper, wiser, somehow more than human. This is not to say that Dovey doesn’t find fertile territory within the abstraction of animality; indeed, she creates, and makes wonderful use of, an emotional distance through which human pain is refracted and made new. But there is never any bowing or scraping, no easy laughs or vulgar caricatures. Dovey’s artistry ensures that every revelation feels utterly earned . . .

Review by Stephen Sparks

It is partly to shore these beautiful fragments up against the sort of linguistic streamlining of toots into hills and shakes into cracks in drying wood that Paul Kingsnorth chose to write The Wake, his debut novel, set in England during the eleventh century Norman Conquest, in what he calls a “ghost language.” If this is his sentiment, he has imposed it on our twenty-first century vernacular to create a language which, against all odds, works. This language, an adapted version of Old English as it was spoken prior to the introduction of French words and influences that arrived on England’s shores along with William the Conqueror, has been made legible to modern readers by the removal of its most foreign elements . . .

Review by Lauren Goldenberg

Barbara Comyns's unique quality and authority of voice is already present in her second novel Our Spoons Came from Woolworths, now coming back into print from NYRB Classics sixty-five years after its first publication. Comyns’s skill is subtle and surprising as she tells the tale of Sophia, a young woman facing down one emotional (and physical) endurance test after another. On the copyright page Comyns has a note that I didn’t notice until after I had read the novel: “The only things that are true in the story are the wedding and Chapters 10, 11 and 12 and the poverty.” The frank bleakness of Comyns’s note almost made me laugh, even as it heightened the tragedy of Sophia’s story all the more . . .

Review by Rebecca Lentjes

Despite his lifelong resentment towards the educational and musical establishment, Partch’s curiosity persisted throughout his whole career, and it was this curiosity that led him to seek out ignored sounds, found sounds, and new sounds. He heard music everywhere: in the forests of California, in the grunts and growls of illiterate hoboes, and in the tones between the notes of the ever-dreaded twelve-tone scale. Even more significantly, he heard this music as an element of storytelling rather than as an event in itself. Partch never allowed any one element of his music theater—not even the music—to dominate the whole. Instead, the usually “separate and distinct” elements of music theater coalesce to form another world, so that the parsing of these elements is made impossible. With Bitter Music, Partch conveyed his memories of the Great Depression via speech and graffiti, letting the music of the human voice transmit both the drama and realism of the human experience. Thirty years later, with Delusion of the Fury, he had transcended the limitations of words, and was able to convey tragedy, comedy, and divine justice in the knowledge that “reality is in no way real.”

Review by Henry Zhang

Grammar, for Diego Marani, is a set of divisions that result from interpreting one’s self and language. Meaning is differential: the raw material of people and language must be defined in opposition to each other, and in time, these differences sediment into things such as nationality and religion. And eventually, like a piece of chalk scrawling without a hand, this differential construction comes to be forgotten; the nation comes to see its identity as something positive and natural, stemming from providence. Yet each division, in the instant of its being drawn, gives hint of its own unnaturalness . . .

Review by Tyler Curtis

Subsumed by a strange growth, the protagonist of Guadalupe Nettel’s story “Fungus” concludes, “Parasites—I understand this now—we are unsatisfied beings by nature.” The sentence transitions ever so slightly, ever so gradually from “it” to “we” in referring to the fungal infection, but the effect is glaring in retrospect. She contracted the infection from an extramarital affair, and it’s spread all across both their bodies. As her unrequited obsession continues to grow, so does the fungus, in a manner both horrific and tinged by humor (“My fungus wants only one thing, to see you again”), eventually becoming indistinguishable from the fabric of her desire. Like “Fungus,” each story in Guadalupe Nettel’s Natural Histories pairs its characters with unknowable creatures whose trajectories parallel the inevitable disintegration of their domestic comfort. On top of the fungal fever dream: betta fish exhibit strange behavior and fight savagely as a woman’s postpartum depression grows apace with her husband’s increasing distance; an exotic snake appears while a father longs for his ancestral homeland; a cockroach infestation reaches a head as a family reaches a new apex of madness; a pregnant cat births a litter, subsequently disappearing as a doctoral candidate aborts her pregnancy . . .

Review by DeForrest Brown Jr.

Kalma and Lowe work very differently, operating with different rhythms, but each brought an equal amount to the table, and to further the idea that this performance was a sort of private dialogue between like minds, they didn’t seem to be playing for the audience. The pieces added up to something of a seance. The idea of “collapsed time” was particularly salient, as there were moments where the pieces felt incredibly short, despite being—in clock time terms—quite extended, generally upwards of ten minutes. Lowe and Kalma's separate philosophies of pattern and movement entangled, sparking new combinations of “cold,” calculating computer work and “warm,” biologic tones.

Review by Xan Holt

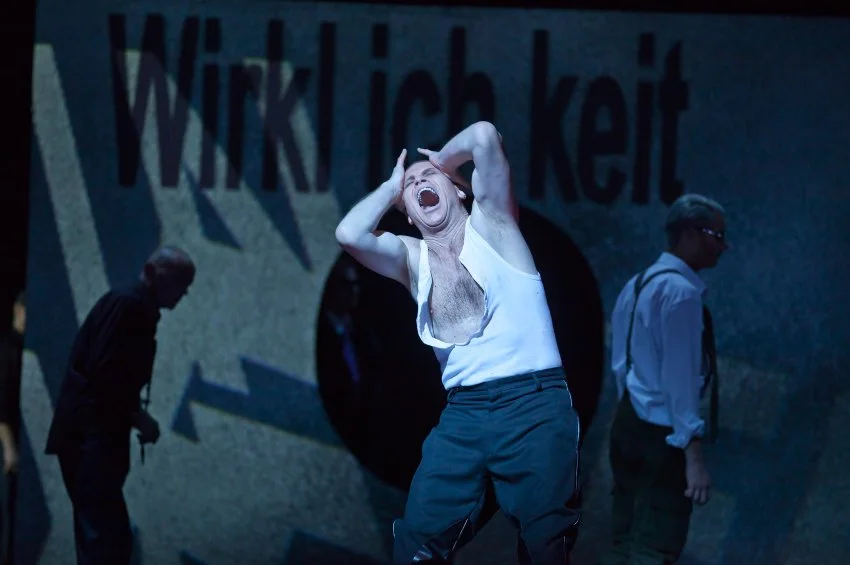

Elfriede Jelinek’s style bears unmistakable formal affinities with this “foreign” pastime of soccer. Her prose features nomadic chains of associations and circuitous sentences that carry the reader along for pages on end before abruptly sweeping him back to where he started. Productions of her performance texts often go on for hours without so much as a hint of a concrete development, to say nothing of a cohesive narrative or series of events. American theater, by contrast, largely shares in the nation’s appetite for palpable conflict, though Jelinek’s dramatic work does find some precedence in the language plays of Mac Wellman and Eric Overmeyer. Over the past forty-odd years of her artistic tenure, she has made a name for herself as one of the most linguistically challenging contemporary European writers . . .

Review by Alexandra Hamilton-Ayres

Although he is heralded as one of the great minimalist composers, Glass doesn’t endorse the term. When he was younger, putting on loft performances in 1960’s New York, he called himself, simply, a “musical theatre composer.” Today, he doesn’t describe himself as a film composer, either, but prefers to define his style as “music with repetitive structures.” In the autobiography, he discusses his visual artist friends from that period—the likes of Sol LeWitt and Richard Serra, who were the “official” minimalists. Because Glass associated with them, his music was correspondingly branded as such. He also writes about working with conductors who presumed his music was “minimalist” in a derogatory sense—in other words, that it was just a mere series of repetitions—and so didn’t bother to rehearse it properly, until they found out, all too late, that the score in question was far more intricate than all that, and was actually constantly evolving. It has always been the case that the superficial simplicity of a piece of music is only ever a mask of elegance, concealing a far more complex sonic journey. The assumption that Glass is therefore easy to play is a foolish one. This is also true of J.S. Bach’s music, where the melodies are simple and clear, yet the harmony is meticulously mathematical.

Review by Caite Dolan-Leach

Reading a detailed chronicle of the decomposition of a human corpse might sound like a grim undertaking. And in an obvious way, it is. But Viola Di Grado’s charming prose romps through chthonic worlds of nibbling insects, ammoniac seepage and shattering depression, using language that is both glib and scrumptious. She is a maximalist; her books don’t tiptoe subtly around obliquely concealed themes. She writes about death and depression without pulling any punches. This could sound like a tormented teenager’s self-obsessed ravings or a dull necrophiliac litany, but Di Grado has an almost supernatural ability to know when enough is enough, and she again and again delivers sharp, gorgeous demonstrations that she can do bizarre and lovely things with words . . .

Review by Mark Mazullo

Operatic composers are in the business of constructing selves, and opera singers are bound to be “something,” the kind of people for whom exists the phrase “larger than life.” This has been the case since the turn of the 17th century, when Shakespeare “invented the modern human being” (to borrow from Harold Bloom); and not incidentally, Shakespeare’s career ran contemporaneous with the birth of opera, invented in Italy as a style of “metaphysical song” (to borrow from Gary Tomlinson) that expressed the distance between interior and exterior, thus lending another face to modern subjectivity and its burden of giving names and forms to the nameless and unformed. Amidst all of this striving for “something,” how might a composer tell Lear musically in a way that allows equal time and space for nothing? How might Lear, in the face of Cordelia’s challenge, musically disappear? How might an operatic character occupy the ambiguous space of the unformed with music so unrelentingly forming it?

Review by Mona Gainer-Salim

Interpretation sometimes poses a grave risk to its object of scrutiny. By focusing so much on what art is about, is it possible that we are losing sight of what it is? Yoel Hoffmann’s newest work, Moods, has a peculiar, provocative relationship to the act of interpretation. Following Curriculum Vitae (2009), a dreamlike retelling of the author’s life, Moods continues Hoffmann’s loosely autobiographical project. Hoffmann weaves a rich web of memories, impressions and images, interspersed with frequent ruminations on his task as a storyteller. The text is filled with doubts and second-guessings—the first page alone contains no fewer than five pairs of qualifying parentheses. A playful challenge is aimed at the reader: abandon your assumptions about how a story should be told, abandon yourself to a narrative that moves in a different way, intentionally skirting the conventions of literary form . . .